When James Young left this world for the next one on October 13, just shy of his 89th birthday, he was not just a loving grandfather, father, and devoted husband; he was also still officially working as a systems engineer and consultant for NASA. At an age when most men would have two decades of retirement under their belts and only dusty memories of their professional glory days, Jim was still working on what he loved, helping humankind explore the far reaches of our cosmos and to better measure the condition of our living planet Earth, even as he was losing his own battle with time and gravity itself.

Jim was awarded the space agency’s highest honor — the NASA Public Service Medal — at Goddard Space Flight Center in 1997, following his contributions to several major projects, namely VIIRS, one of the first meteorological sensors sent into space, and the original Thematic Mapper, a program that would later become Landsat. His last major project culminated in the MODIS program, essentially a calibration lab for space. “You know, we don’t give out too many of these,” they reportedly said when they hung the medal around his neck.

Jim’s major contribution to these programs was in optical design and calibration, turning what would otherwise be just pretty pictures from space into very accurate, precise data, used for everything from short to long-range weather forecasting to understanding the earth’s climate. For example, data gathered by MODIS and VIIRS can be used for fire and air quality monitoring, carbon modeling, flood and sea ice mapping, and to accurately determine the temperature of the oceans from space to within a few degrees. And along the way Jim also received two patents, one being the basis for much of the optical spatial characterization testing being performed today on the VIIRS program.

Born in 1929 on a farm in Knox Township, Holmes County, Ohio, Jim looked west, to a world outside his rural upbringing for inspiration, where his beloved cowboy heroes from radio shows like Hop-A-Long Cassidy roamed the plains and took down bad guys. As a young man, he devoured the pages of Astounding Science Fiction paperbacks with tales of exploring new planets and encountering mind-bending alien life. He also read everything he could about Albert Einstein, Buckminster Fuller, and his other heroes of the physical world.

At Ohio State University where he studied physics, Jim struggled to stay in school due to debilitating migraine headaches and a severe stuttering problem, eventually having to take two years off. He found what he needed in personal development (and applying powerful mind-over-matter techniques to his migraine issues) in a group who called themselves the “Synergetic Community.” The members of Jim’s Synergetics community did not care for a theological approach and attempted to create an organization better suited to their tastes, one that was agnostic in nature.

Synergetics completely shaped young Jim’s worldview and, maybe most important to Jim’s future success, helped him tap into a higher state of consciousness, as promised by the handbooks he kept for his entire life. “When the synergetic mode lights up, the mind turns on … .” the handbook reads. “Abilities [he] did not know emerged and [his] thinking becomes faster, more accurate, remarkably clear.” His mentor in the movement, a man by the name of Art Coulter, would later thank Jim on page one of his book “Synergetics, An Experiment in Human Development,” published in 1955. His children would later be raised by Jim’s understanding of the same synergetic principals, focused on the child’s self-determination and parenting with empathy over heavy-handed training.

When young Jim got the call from Santa Barbara Research Center’s Gene Peterson and Dave Shiffman (who would become the mayor of Santa Barbara from 1973-1981), he took a chance on fate with what was little more than a start-up at the time. Jim left his job at Ohio State Research Foundation and, having never been west of Colorado, hit the road in his 1954 Ford Crestline and eventually found a place on the Mesa with some fellow bachelors. SBRC was housed then in the old Marine barracks at the airport. The year was 1957. Soon after he joined, SBRC got its first contract with NASA. Later, it became Raytheon’s Santa Barbara Remote Sensing unit.

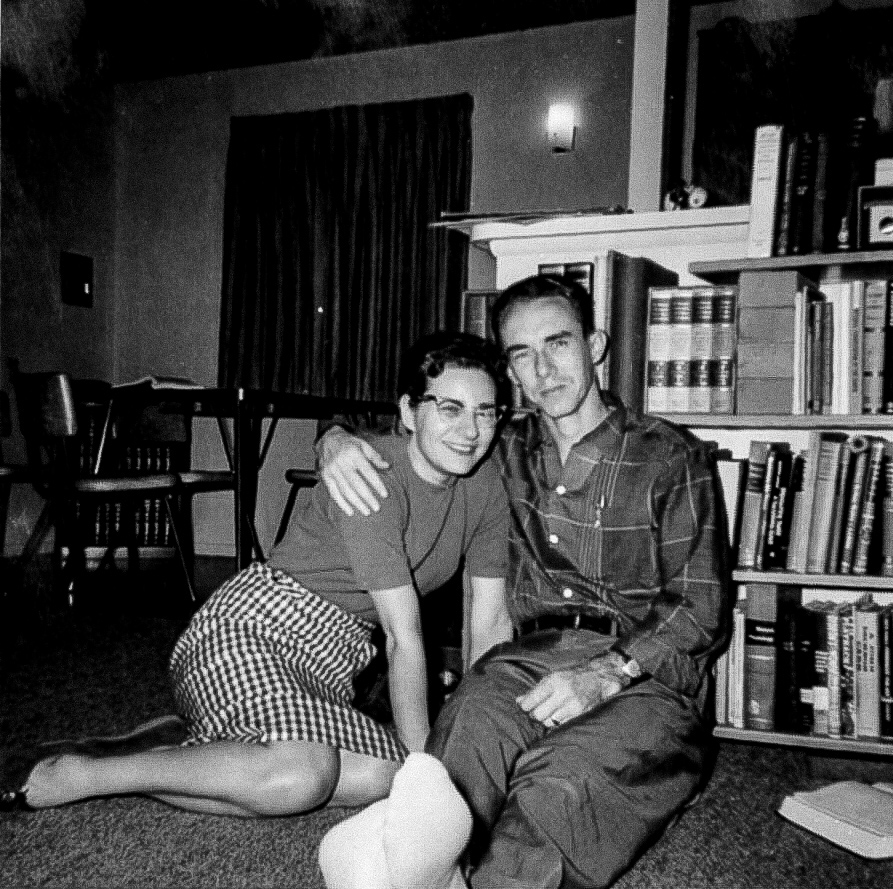

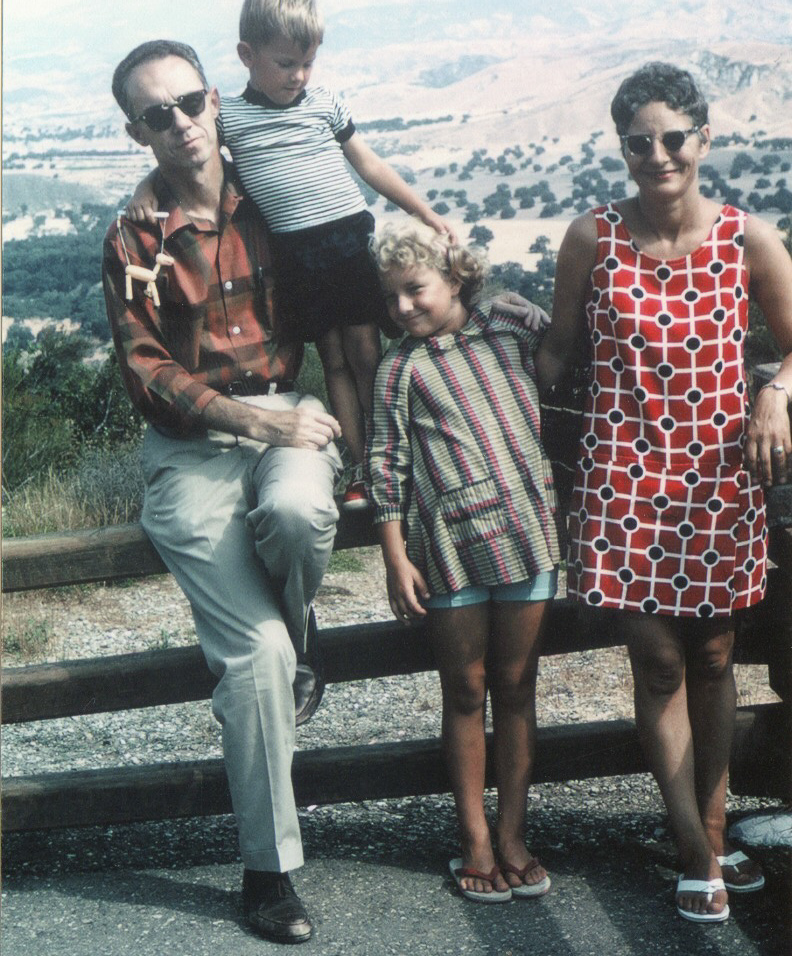

Once in Santa Barbara, Jim met a Welsh nurse by the name of Gladywn Thomas at a Singleton’s Club, sponsored by a local church. Jim came repeatedly knocking on her door, initially as her ride to events at the club but also apparently a convenient “set-up” arranged by a mutual friend. Jim not only had a sweet automobile, but he was intelligent and well-mannered, different than most of the Americans she had met. Jim eventually overcame his acute shyness to make his way into Gladywn’s heart, marrying in Santa Barbara in 1957, and settling down in the hills above Goleta where they raised their children, Lisa and David. They were married for 60 years.

Life in the 1960s-1980s Cold War, booming high-tech community of Goleta was a steady stream of the California dream. Jim would eventually stop traveling to D.C. and Ohio, and his family would grow to include a son-in-law, Chris, and daughter-in-law, Healey. Years later, grandkids Drake and Beck would fill his heart, and he would share the wonders of the universe with them.

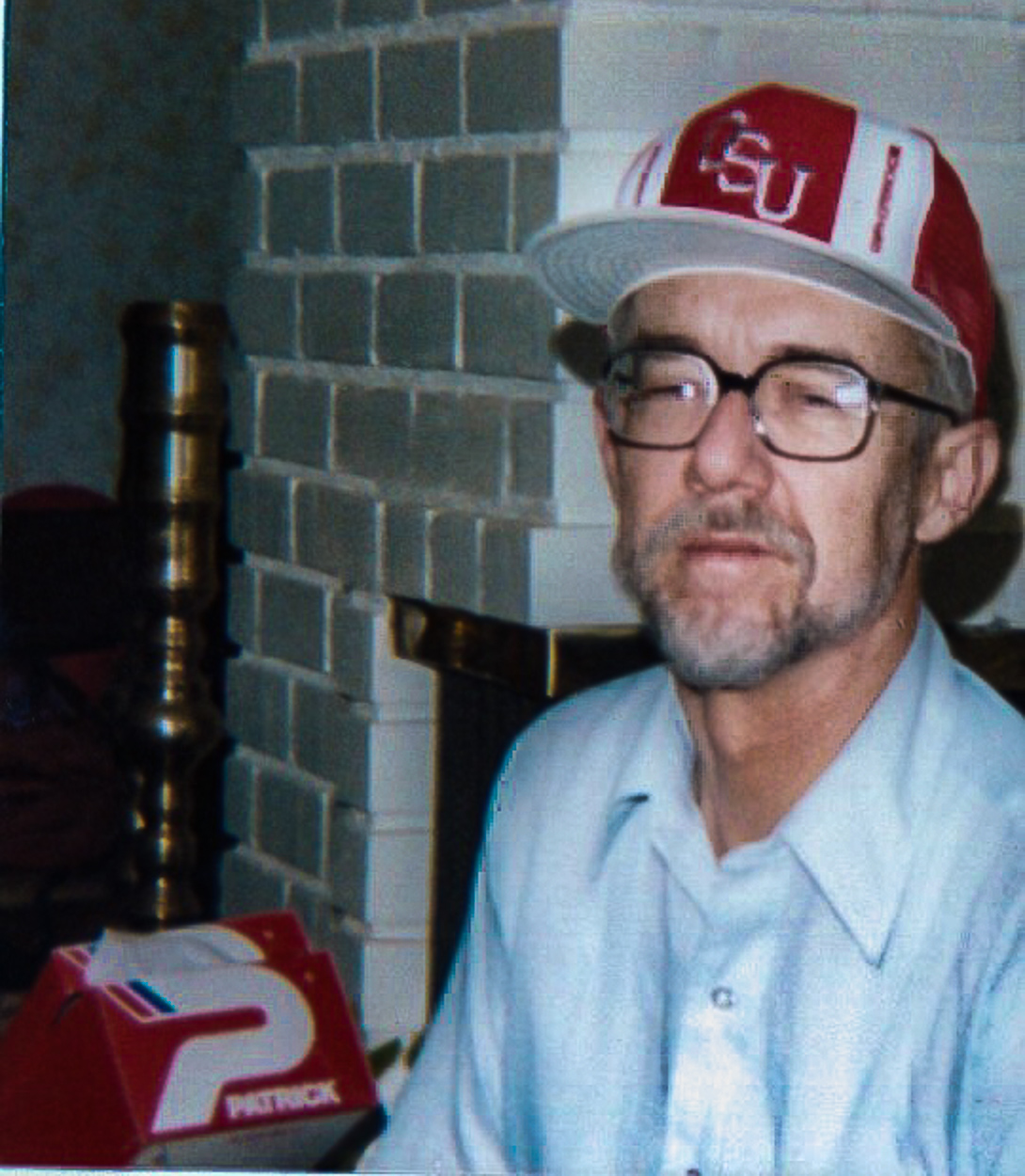

Jim had a very good sense of humor that he used to keep himself grounded. He would often look at you with a knowing twinkle in his eye and make a remark that was both self-effacing and empathetic. The joke he would make, with a disarming chuckle, was typically on him and his simple farm-boy sensibilities. He was a man of basic needs and, as a child born less than two weeks before the stock market crash and the start of America’s Great Depression, he never spent money on anything not entirely essential, keeping cars running well past their prime and owning only one tailored suit in his wardrobe. As a husband and a father, Jim was never once not there for his family and remains there for us to this day. Loyal to family, company, and alma matter for his entire life, Jim was also a diehard OSU Buckeye fan and rarely ever missed catching their football games on television.

Prior to his retirement from Raytheon in 2006, which would last a mere six months before taking the consulting job with NASA, a co-worker had asked Jim what he liked to do in his spare time. “I like to make up fun physics problems and solve them” was his response. But Jim didn’t just love solving physics and engineering problems, he loved sharing what he knew with others and was a teacher to so many of the engineers working with him, helping so many along the way.

Tom Pagano, MODIS systems engineer manager, credited Jim as “the brains behind the theory of radiometry” and cited his work as “a contribution to humankind’s expanded understanding of calibration and remote sensing instruments. He contributed to just about every major flight program we’ve had at SBRS.” But Pagano added that Jim’s skills weren’t limited to calibration. “He taught countless individuals how to do analysis. He is a legend around here.” Fellow engineer Dick Cline at SBRS (owned by Hughes Aircraft at the time), who worked under Jim for 28 years and shared an office for nine of those years, shared that even among NASA’s biggest and brightest technical review experts, Jim “stood tall. His technical skills were/are widely recognized. His words may have been slow, but his communication skills were outstanding.”

And while praised as a “great mentor to so many,” the “Mahatma of calibration” by his peers, Jim found simple joy in the pursuit of his life’s work and not in any form of self-aggrandizement. When asked if he was on hand to witness the historic Viking Spaceship launch to Mars, equipped with the Infrared Temperature Mapper instrument he designed for NASA for the Mars Observer program and our return to the Red Planet, Jim responded “I was invited. I didn’t go. That does not personally turn me on.”

Jim was also a deep thinker in the spiritual realm, holding on to a firm belief that there is an afterlife and we simply “close one door (in this life) to open another in the next.” Among his vast collection of technical books, he also was keenly interested in literature around the relationship between physics and spirituality, looking for the mathematical equations that made sense of our existence.

Jim was a loyal and earnest man who lived for his family and his life’s work. “I am most fortunate to do the things I like to do,” he was known to say. And I had the extreme fortune in life to call this brilliant, kind-hearted soul my dad.