The Black Dahlia Never Dies

The Unsolved Mystery of One of the 20th Century’s Most Sensational, Brutal Murders

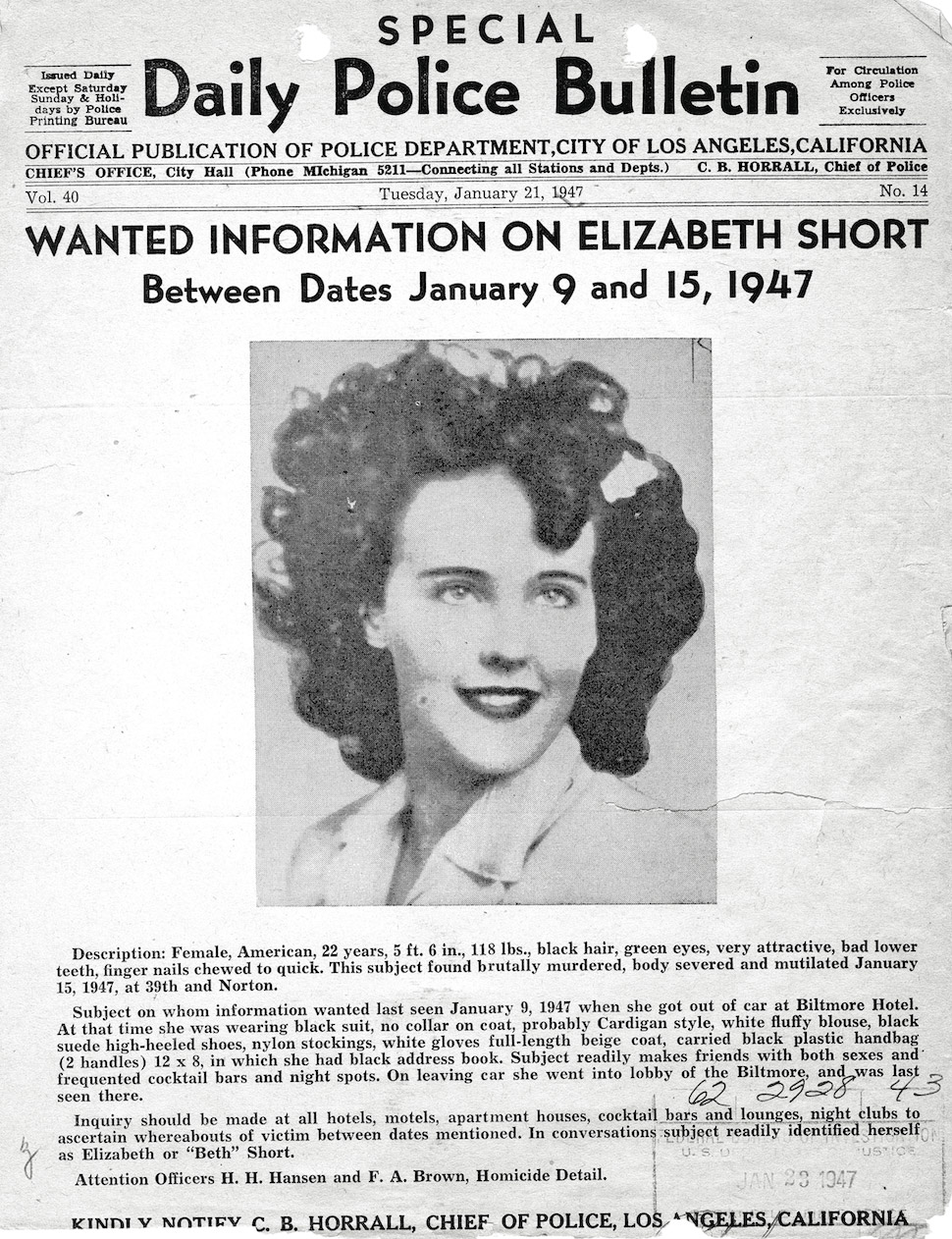

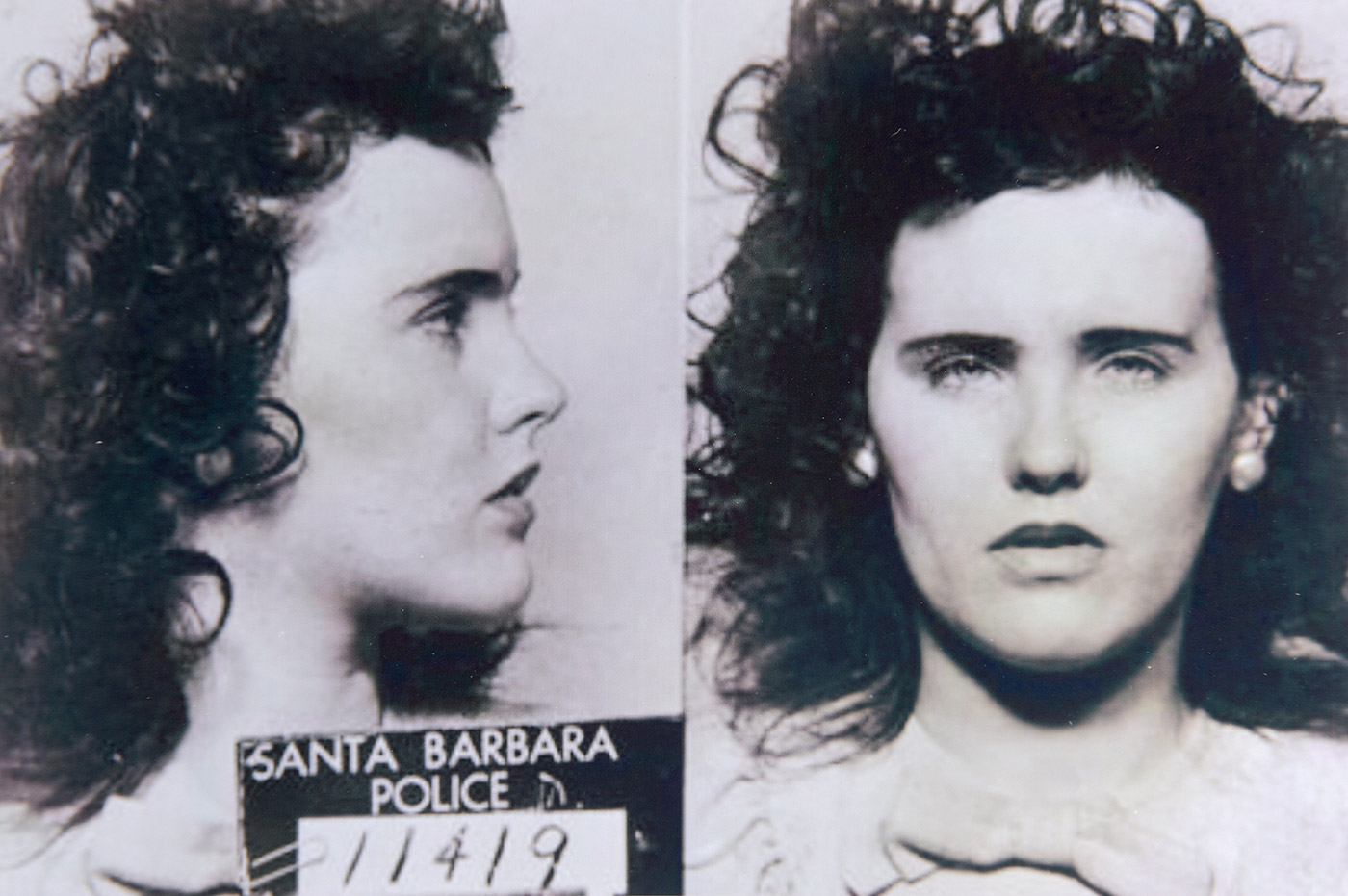

On a September night in 1943, a Santa Barbara police officer worked the camera for a routine mug shot. Staring into the lens was a 19-year-old female arrested at El Paseo Restaurant’s bar for underage drinking.

The resulting black-and-white photograph, with the young woman’s dark, curly hair framing a face both defiant and vulnerable, has since become iconic.

It’s the face of Elizabeth Short, known now as the Black Dahlia, who was brutally murdered in Los Angeles shortly after World War II. The 1947 crime grabbed national headlines when her body was found surgically bisected at the waist, drained of blood and bizarrely mutilated. The murder remains unsolved.

Another high-profile cold case with Santa Barbara connections — the Golden State Killer — resurfaced in April with the arrest of Joseph DeAngelo, 72, a Sacramento County resident who has been charged with a dozen homicides from the 1970s and 1980s, including a pair of double murders near Goleta.

The 71-year-old Black Dahlia case isn’t likely to get a similar resolution via arrest and courtroom prosecution. The killer is probably dead, so no formal conviction will be had. Even so, the grisly crime has staked out a lasting hold on the public imagination.

Santa Barbara Connection

In 1943, Elizabeth Short lived briefly in Santa Barbara in a courtyard bungalow still standing on West Montecito Street, now hidden behind a concrete wall next to a 7-Eleven. Earlier that year she worked at Camp Cooke, a U.S. Army training post where Vandenberg Air Force Base stands today. Her time in Santa Barbara County nevertheless figured prominently in Los Angeles detectives’ investigation into her murder and continues to stir the interest of many today — including writers, filmmakers, amateur detectives, a Santa Barbara City College professor, and, more recently, a former CIA officer, Douglas Laux, who is reexamining the case for an upcoming podcast series.

Laux, like many, had heard of the Black Dahlia but knew little beyond the famous nickname. Through his research he has since discovered the picture often painted of Short — including that she was a prostitute — is false. “Hopefully with the podcast, people will unlearn a lot of these ‘facts,’” said Laux, a New York–based writer who produced a recent Discovery Channel show tracking drug lord Pablo Escobar’s money.

The Black Dahlia podcast is expected to be released this fall and will run about 10 episodes.

Rose Tattoo

The local ties from Short’s brief stay in Santa Barbara radiate primarily from the involvement of the arresting police officer, Mary Unkefer, in ways that became public after the murder as well as through connections uncovered more recently by the Santa Barbara Independent.

After the murder, Unkefer told newspaper reporters Short had stayed with her in the days after the arrest until the juvenile court released her on probation and sent her home to Massachusetts. “She was very good looking, with beautiful dark hair and fair skin,” she told one Los Angeles paper. “She dressed nicely and was a long way from being a barfly.”

Unkefer let drop another detail: Short had a rose tattoo on her left thigh, something that turned out to be a gruesome piece of the case. The murderer cut the tattoo from Short’s thigh and reportedly inserted it into a body cavity, records from the period indicate.

Details about the tattoo were intentionally withheld from the public as a way to weed out the many people who came forward to confess to the murder at the time.

“Mary Unkefer is one of the few people who had ever seen it,” said Laux. Unkefer’s comments to the press are the only reason the public knows about a detail the police essentially hinged their case on, he said. Since the Los Angeles Police Department considers the case unsolved, its files are sealed, and the tattoo’s exact appearance remains a mystery to this day.

Lens to the Past

Short’s arrest report was made public for the first time by the Santa Barbara Police Department at the Independent’s request, according to Sergeant Joshua Morton, a current department spokesperson.

The report shows Short lived in the city only a week before the El Paseo bar incident. She then was moved to a house owned by Unkefer, located where the Victoria Court parking lot is today.

As the arresting officer at the time, Unkefer almost certainly would have taken the young woman’s now-famous mug shot as well as her fingerprints, Morton said. The FBI used those arrest fingerprints to identify the body, according to the agency’s public case file.

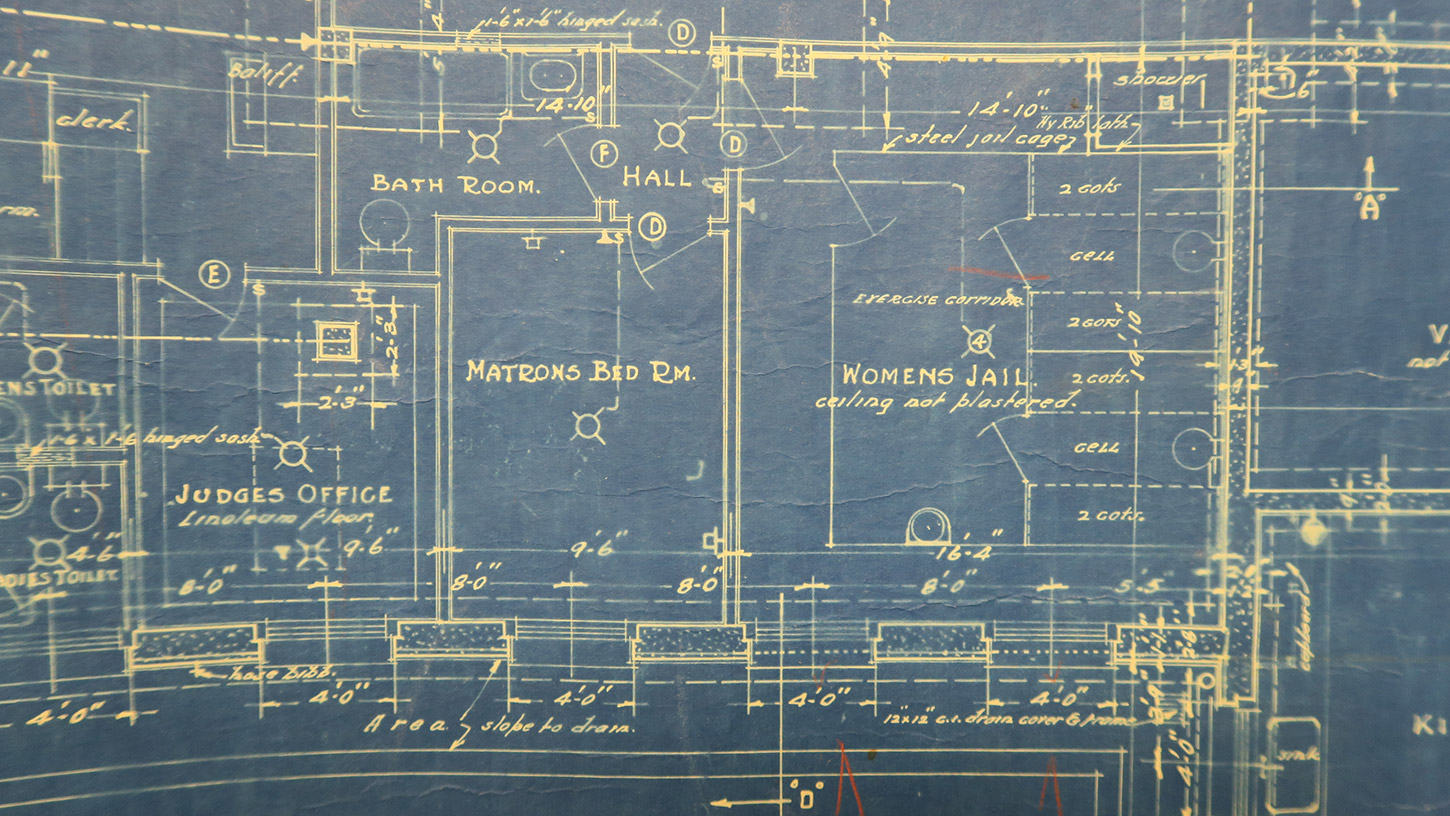

Santa Barbara was a smaller town back then, and the police department operated in the basement of City Hall, across the street from El Paseo. Blueprints show the department had a police court, separate jails for men and women, a dedicated “tramp” cell, a matron’s bedroom, and more crammed into the space. Today, the original 1920s-era mail chute is still visible in the basement hallway.

FBI files show that Short applied for a clerk job at Camp Cooke near Lompoc in January 1943, a process that also sent a set of her fingerprints to the agency’s database. She was hired to work at the base’s post exchange, essentially a convenience store for service members. Short was featured as the Camp Cooke “Cutie of the Week” in the base publication the following month. A photo caption attributes the “steady increase of business at PX 1” to the newly arrived 18-year-old. By September, Short had moved to the Santa Barbara bungalow. Less than four years later, she became the murder victim in one of the most sensational cases in postwar America.

Death and Fame

On January 15, 1947, a mother pushing her young girl in a stroller found Short’s nude body near the curb of a vacant lot in a southwest Los Angeles neighborhood. Severed in two, the body was posed oddly. Gashes roughly three inches long had been carved across her face from the edges of her mouth, among other grisly defilements.

The freakish details created a national sensation that still fuels books, movies, TV shows, and pop culture more than 70 years later. You could burrow down a Dahlia rabbit hole for years.

At one end are things bizarre. Plug the hashtag #BlackDahlia into Instagram, and you’ll find dead-girl tattoos, faces made up with red-gashed cheeks, souvenir shots at a mural in Hollywood’s Museum of Death, and portraits — some in full costume — at Short’s gravestone in Oakland. A Michigan death metal band called The Black Dahlia Murder is currently on a U.S. tour.

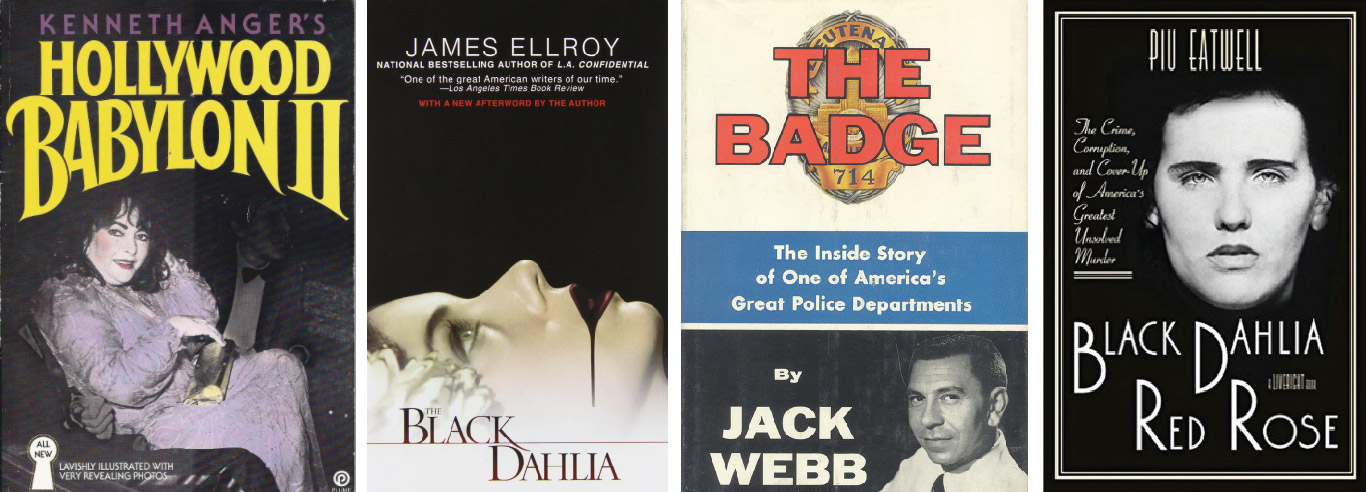

At the other end you will find writers fascinated with the murder. Many readers are familiar with the case through acclaimed author James Ellroy’s 1987 novel The Black Dahlia, which presents a fictional account (and became a 2006 Brian De Palma film that flopped). Ellroy, whose mother was murdered when he was 10, has told interviewers he became fixated with the case after reading about it in Jack Webb’s The Badge when he was 11, effectively fusing the two murdered women in his mind. In 1979 John Gregory Dunne included a fictional account of the Dahlia murder as an element in his novel True Confessions. The book was later made into a popular film written by Dunne and Joan Didion, his wife, and starring Robert De Niro and Robert Duvall. With the publication of avant-garde film director Kenneth Anger’s book Hollywood Babylon II in 1984, interest in the murder spread, as it included a graphic crime-scene photo of Elizabeth Short’s body splashed over two pages, bringing gory details of the horror to a large audience for the first time.

The crime shows up in high art, in jazz composer Bob Belden’s Black Dahlia suite on the Blue Note label, and in two Black Dahlia graphic novels (one adapted from Ellroy’s novel by director David Fincher). Another book, Exquisite Corpse: Surrealism and the Black Dahlia Murder, links the murder to surrealist art. On TV, the slaying was part of the first season of FX’s American Horror Story in 2011.

Then there are the many books claiming to solve the murder. The most recent, Black Dahlia, Red Rose, by Paris-based author Piu Eatwell and released last October, pins the crime on one of the original suspects, Leslie Dillon. In May, seven months later, a Paramount Network television series, It Was Him: The Many Murders of Ed Edwards, was already making the case for another man as the killer.

Black Dahlia Avenger, originally published in 2003, was number one on the New York Times best-seller list. Written by retired LAPD detective Steve Hodel, the book alleges Hodel’s father, an L.A. physician, was the murderer. Hodel has since updated the book and expanded his accusations, suggesting his father was also responsible for the Zodiac murders in the Bay Area and many others. The elder Hodel was investigated by the LAPD as a suspect in Short’s murder but not arrested for the crime. A Hodel family tale is coming to the TNT network this year as a six-episode show, One Day She’ll Darken, starring Chris Pine and produced by Wonder Woman director Patty Jenkins. The series is based on the autobiography of Fauna Hodel, Steve’s niece, and includes the doctor and the Black Dahlia link.

Other alleged suspects were previously fingered in the once-popular 1990s titles Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder by John Gilmore, which pegged the crime on Jack Anderson Wilson, and Janice Knowlton’s Daddy Was the Black Dahlia Killer. Newspaper accounts after the murder carried ongoing stories about arrests and confessions; Leslie Dillon, Robert “Red” Manley, and Joseph Dumais were top suspects at the time.

Folk singer Woody Guthrie was briefly a suspect. Other well-known names were accused in books, including director Orson Welles and mobster Bugsy Siegel, allegedly acting at the behest of Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler. (Neither Welles nor Siegel were ever suspects in the case.)

“There is something about the Black Dahlia case that just attracts crackpots and liars,” said Larry Harnisch, a retired Los Angeles Times journalist who is also writing a book on the topic. In 1997, Harnisch wrote a 50th-anniversary piece on the crime for the Times, and he has continued researching Short and the murder ever since. He contends there is no documentation showing Short was a prostitute or any of the other lurid rumors that buzz around the case involving porn films, abortion rings, and the like.

Even the tragic drama often associated with Short, that she was an aspiring actress who achieved fame only in death, lacks evidence, according to Harnisch. She had not even been in a school play, he found.

The Real Elizabeth Short

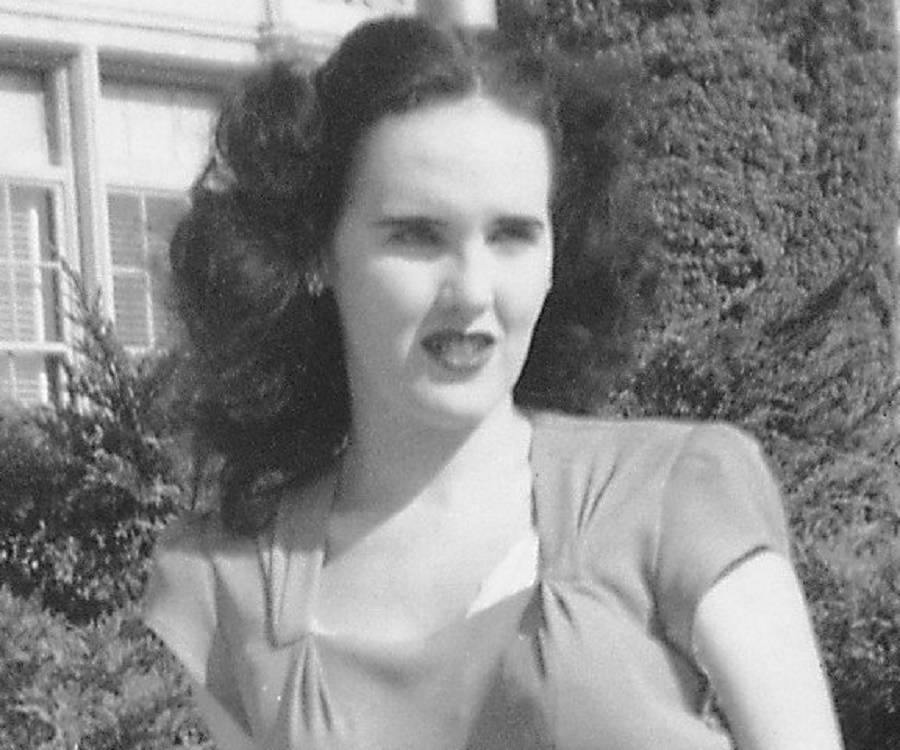

A brief outline of Short’s life goes like this: She was born in Boston in 1924, the third of five girls. In 1942, after learning her father was in California — he had abandoned the family during the Great Depression — Short moved to the Vallejo area to live with him. The reunion was an unhappy one, and she soon took the job at Camp Cooke, moved to Santa Barbara, and eventually traveled around the country.

A pretty, social girl, Short dated often but seldom seriously. She was not known as a drinker, despite the El Paseo incident, and worked regularly as a theater usher, cashier, and waitress.

She became engaged to a U.S. Army Air Force pilot, but when he died in an August 1945 plane crash in India, “her life really unraveled,” said Harnisch. “I’m not sure she ever worked again after that.”

Her final year and a half morphed toward parasitic behavior. She mooched meals, rides, housing, and money. She had excellent radar for picking nice people who would be sympathetic to the sad story about her fiancé’s death, Harnisch said.

By July 1946 she had returned to California, spending time in L.A. and San Diego. She received the Black Dahlia nickname months before the murder, according to Harnisch. Soda fountain customers at a Long Beach drugstore she frequented noticed her dark hair and good looks and probably made a play on a popular movie, The Blue Dahlia, a mystery about a returning soldier falsely accused of murdering his unfaithful wife.

Short, then 22, was last seen alive in the ornate lobby of the Biltmore Hotel in downtown L.A. about a week before her body was found.

Up on the Hill

“This case is why I’m sitting in this office,” said Professor Anne Redding, department chair for Santa Barbara City College’s Justice Studies program. Redding first encountered the Black Dahlia case when, as a student at Cal State L.A. in the 1980s, the professor in a sex crimes investigations class showed the coroner’s 8′-by-10″ photos of Short’s body.

“I had never seen real-life brutality and horror like that before,” Redding recalled. The jolt inspired her to learn “as much as I could about sexually motivated murders,” she said.

Knowledge about psychosexual pathology — for future law enforcement officers as well as potential victims — offers the best chance to prevent such crimes, Redding believes.

She now teaches a class, The Study of Murder, developed in part as an homage to that original course featuring the Black Dahlia.

Shared interest in the case led to a friendship between Redding and James Ellroy, who met at a Black Dahlia exhibit at the Los Angeles Police Museum in 2012. Ellroy spoke at City College that year at Redding’s invitation. Laux, preparing for his podcast, also spoke with Redding at length.

Redding herself doesn’t endorse anyone’s theory regarding who killed Short. She also bristles at the implied message buried in the wannabe-starlet-turned-prostitute myth: that Short somehow had it coming. “She was not a femme fatale — she just wasn’t,” Redding said. “She was sad, lonely, and pretty much homeless at the time of her death.”

The crime’s lasting fame is perhaps more remarkable because it involved just a single victim. It is one drop in a cold-case sea: Some 211,000 homicides in the U.S. went unsolved between 1980 and 2015, a Scripps News analysis found. Yet Black Dahlia fascination lingers.

As a mystery, the case has all the elements of a good noir tale: a beautiful woman, postwar Los Angeles, Hollywood, a catchy title, and no easy resolution. At center is a victim who knew the truth, and in the end, it’s Elizabeth Short’s version we long to know.