Maceration Magic at Central Coast Group Project

Scott Sampler Employs Punk-Rock Ethos and Extreme Winemaking in the Buellton Bodegas

“Every Sunday, I grew up eating sauce,” said winemaker Scott Sampler, who was raised in Los Angeles during the 1970s and ’80s by an Italian-American mother and African-American, World War II–vet-turned-commercial/fine-artist father. Hot on the city’s emerging culinary scene, they introduced good food and sips of wine to their son at an early age. By the time he hit Berkeley to study philosophy, fine art, and film theory in 1985, Sampler found that he was addicted to slow-cooked sauce and started stewing it himself as a cure for homesickness.

“The ingredients profoundly affect the outcome of your perceived skill,” Sampler told me a couple of months ago inside his slender slice of the Buellton Bodegas, the warehouses-turned-wineries complex where he’s made his Central Coast Group Project wines since 2013. Wine-wise, that means sourcing top-quality grapes, which he does from vineyards such as Larner and White Hawk. But sauce-making also taught him about the differences between a fresh concoction and one that’s cooked down to achieve richer textures and flavors. “It transitions the ingredients,” he explained. “You get a deeper essence.”

That lesson looms over Sampler’s winemaking, which blends the antiestablishment ethos of punk rock with old-school techniques from classic regions such as Barolo. While many winemakers allow their wines to soak on their grape skins for a couple of weeks, maybe a month, after primary fermentation to extract more color, flavor, and texture, Sampler lets his stew far longer — more than nine months, in fact, for certain lots of the 2015 and 2016 vintages. Though this isn’t completely unheard of in corners of the Old World, the super-extended maceration increases risk of spoilage on multiple fronts, especially when Sampler barely uses any sulfur as a preservative.

And that totally freaks out neighboring winemakers. “People are going to be irritated, even here,” he said of the Bodegas, where most people have pressed their wines into barrel by Thanksgiving each year. “When I roll the press out in January or February, people are like, ‘What the fuck is he doing?’ — angrily. It creates a little bit of tension. It’s almost like a punk-rock gesture.”

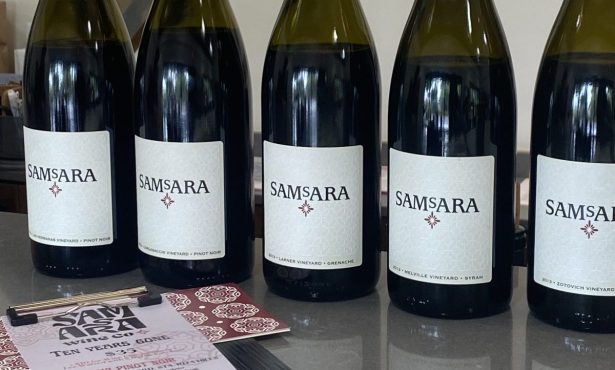

So far, though, the Central Coast Group Project wines are working out. There are a couple of intentional and intriguing oddballs — like the sherry-ish Blood Orange viognier and see-through yet high-octane Twilight Idol grenache — but the bulk of Sampler’s wines are richly flavorful and framed by smooth, resolved tannins. In a curious way, they seem to taste more like themselves, as if these extreme winemaking measures somehow double down on each vineyard’s unique qualities.

“The whole point is to push the fruit back,” said Sampler, noting that, thanks to California’s sunshine, the ripeness of grapes is never a problem. “It’s more like directing, knowing what you’re trying to get from their performance.”

Directing and screenwriting were what Sampler did before wine, natural pursuits for an Angeleno raised amid the “heightened aesthetic experience” cultivated by his parents, who resided in Los Feliz before it was cool. They divorced when he was 13, so he wound up splitting time on the Westside with his dad and attending Beverly Hills High, where his friends’ parents had serious cellars. He recalls a 1967 Georges de Latour as a “momentous occasion,” around the same time he was hitting the Sunset Strip for seminal punk-rock experiences courtesy of Black Flag and X.

At Berkeley, he sharpened his wine knowledge on bottles from legendary importer Kermit Lynch and ate out regularly at Chez Panisse, where hashish smoking and old vintage imbibing was the norm. “The time was so much wilder then,” he said with a booming laugh. “It was a more permissive culture.”

Upon returning to L.A. to pursue a film career in 1990, Sampler moved downtown into what was then called the “artists” district, where the vast majority of tenants were indeed artists. “Now it’s called the Arts District,” he said. “When I left, there were zero artists.”

That flat is where he started a dinner group called Sauce Fest with three friends. They’d prepare multicourse dinners while sipping on the carefully selected bottles that each brought. “It had to be good, or you would get ridiculed and denigrated and practically hazed,” said Sampler, who became close with retailers at K&L Wine Merchants and Silverlake Wine. “It got competitive.”

Following a bad breakup, Sampler escaped to a friend’s property in the Malibu mountains and found the landscape to be a cross between Spain’s rocky Priorat and Italy’s coastal Bolgheri. He and his friend decided to plant a vineyard in 2009 and the following year started making wines from Santa Barbara grapes at a custom crush facility in Camarillo with the help of Steve Clifton, of Palmina and Brewer-Clifton. (The Malibu vineyard never bore fruit and burned down in a 2013 wildfire.)

In 2011, Sampler moved into a Winnebago at Rancho La Viña on Santa Rosa Road near Lompoc and made wines alongside Joe Davis of Arcadian, Brett Escalera of Consilience, and Bruno D’Alfonso and Kris Curran of D’Alfonso-Curran Wines. “That was like going to enology school,” said Sampler, being surrounded by four renowned winemakers with strong opinions on how best to do it. He then moved into a double-wide trailer in Buellton with Curran’s mom — “It was like a kitschy, quirky movie,” he recalled fondly — and made wines at Standing Sun for a while.

Then the partnership with his Malibu friend fell apart in 2012, and Sampler had to essentially start over. He scribbled a business plan on a napkin at the Hitching Post and was able to raise enough money in two weeks to make about 300 cases and launch the Central Coast Group Project as his very own brand.

The next year, he moved into the Buellton Bodegas as one of the original tenants. “This has been a godsend,” he said. “In the privacy of my own space, my bins can soak for 200 days, and it doesn’t bother anyone.” He still lives in L.A. but is often at the winery for extended periods. “It’s like doing a tour of duty on a nuclear sub,” he said. “When harvest comes around, sometimes I get stuck in the sub.”

The sub is also home to Sampler’s boundary-shattering wines, such as Blood Orange, an orange-colored wine that started with viognier and then fermented through the two months of harvest as sorting-table drippings of various red grapes got tossed into the mix. “It’s a great food-pairing wine,” laughed Sampler, his salt-and-pepper afro bobbing away. “It’s great with hot dogs.” It’s also big in Manhattan, where much of the batch was guzzled.

Then there’s Twilight Idol, which spent 140 days on skins to make a transparent yet 16.4 percent alcohol grenache, unlike anything you’ll find anywhere. “You can see the edge, just before death,” said Sampler of how deep into the maceration mystery he took this wine. His other red wines, such as the Captain Kierk syrah, Barrington Hall Wine Dinner Special Cuvée, and Happy Birthday mourvèdre, are more familiar in style, albeit whimsically named.

Today, Sampler makes a lot of wines, but not much of any of them —7-14 individual bottlings (most are $75 each) totaling 900-1,200 cases per vintage. Many sell in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., but he is open for tastings by appointment in Buellton. And a visit may grant a glance of his latest experiments, which grow increasingly adventurous with time.

“I’m pushing things a little further,” said Sampler. “I have more of a sense of how far I can go.”

See ccgpwines.com.

Editor Explorations:

Join our senior editor and resident wine expert Matt Kettmann on a river cruise through Bordeaux this October. Learn more over a glass of wine at Grassini Family Vineyards tasting room (24 El Paseo) at a free info session on Wednesday, February 21, 5:30 p.m. See sbindytickets.com for more.