John Nava Brings Painting and Tapestry to Sullivan Goss

On Display is a Masterpiece of Contemporary Tapestry

The craft of weaving has given us many of the most durable metaphors we have for high levels of communal integrity. It’s no accident that when people reach for the best appropriate way to praise a multicultural society, for example, they often speak of it as a “grand tapestry.” And there’s a reason for that. Even more than in a “colorful mosaic,” where each individual chip retains its essential color identity, the threads of a fabric woven by the Jacquard process blend optically into something new — a combination of values that is perceived by the human eye as a single color.

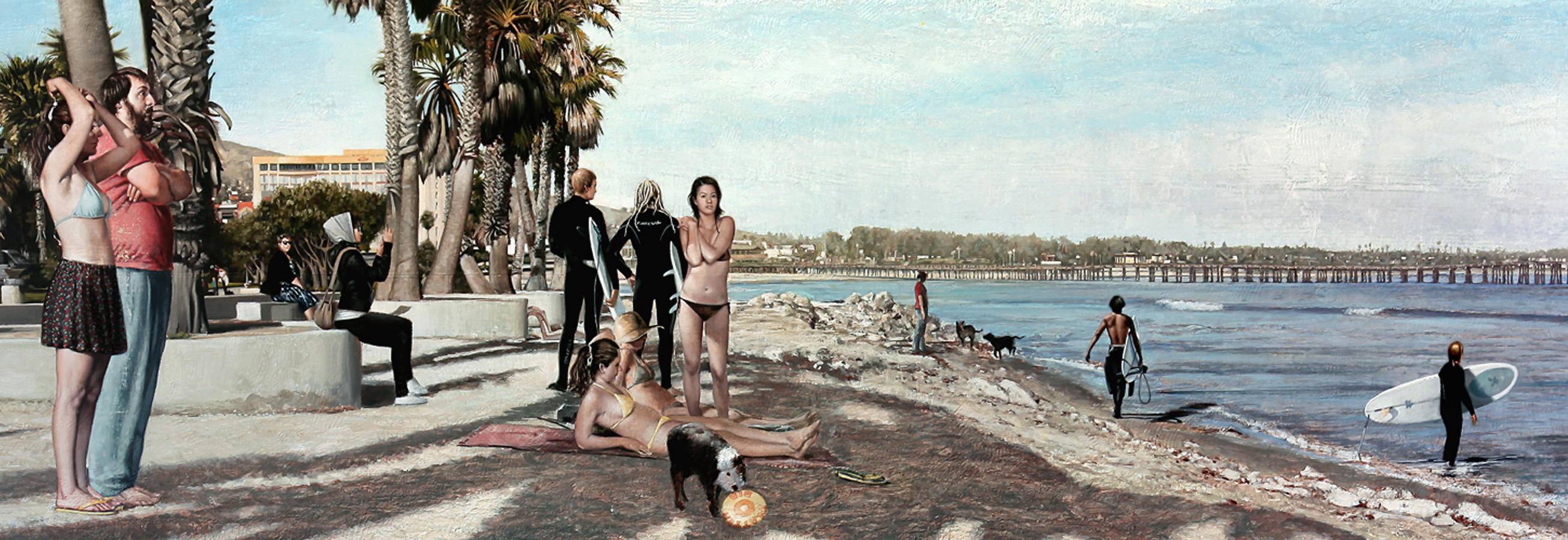

In a spectacular new exhibition at Sullivan Goss, the Ojai-based painter John Nava, an expert on the history of artistic techniques, has produced, with the help of a computer-aided Jacquard weaving process, a 27-foot representational panoramic tapestry depicting the crowd at Surfers’ Point, a public beach in Ventura. The tapestry, which is called “Big Platter,” is in turn derived from a smaller, but still substantial, painting of the same name, along with multiple figure studies and a digitally assisted technical process that begins with Nava in Ojai before passing through the Jacquard looms in Belgium, only to return to the United States when the completed work is ready for display.

The architect Le Corbusier, a devotee of the tapestry as an art form, once referred to these imposing works of fine art as “nomadic murals.” To see Nava’s “Big Platter” at Sullivan Goss is to realize what he meant. The scale of the work is commanding, yet the technique employed by the artist to render the image, a species of pointillism, softens its impact by calling attention to the three-dimensional character of the medium. Nava, who is best known for his extraordinary commissioned tapestry work in the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles, was inspired to make this piece by his research into pointillism as practiced by the 19th-century French artist Georges-Pierre Seurat, and in particular by Seurat’s iconic “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte,” a large, densely populated painting that hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. Seurat studied the science of color as elaborated in the work of another Frenchman, Michel Eugène Chevreul, a chemist who, as part of his job directing the dye works at the Gobelins tapestry factory in Paris, invented the color wheel of primary and intermediary hues. French painters such as Eugène Delacroix and Seurat were quick to grasp the significance of Chevreul’s observation that the simultaneous contrast of colors in adjacent threads could, at a distance, create the optical effect of a single color.

In Nava’s work, the technical means of production is always in critical dialogue with the subject matter and the execution. The artist built this wide horizontal panorama out of dozens of figure studies, several of which are on view in the show at Sullivan Goss. Echoing the decidedly un-aristocratic, subtly utopian feeling of Seurat’s Sunday in a public park, Nava finds the beauty and humanity in a collection of beachgoers who, while not motley, are nevertheless conspicuous only in their relative disregard for the conventions of covering up and remaining fully dressed that typically apply in public places. Bathing suits, wetsuits, T-shirts, and shorts — they are all here, and the people wearing them all receive equally reverential treatment from the painter. Stepping definitively away from the hierarchical representational schema of history painting and official portraiture, Nava, like his master Seurat, elevates the leisure of the middle class to the status of a masterpiece.

411

John Nava’s Painting and Tapestry exhibit runs through December 31 at Sullivan Goss, An American Gallery (11 E. Anapamu St.). See sullivangoss.com.