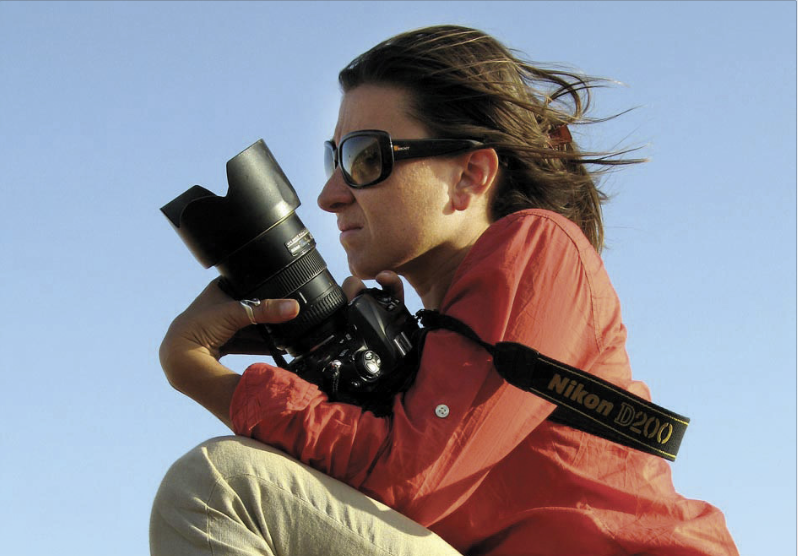

Lynsey Addario Comes to UCSB

Award-Winning Photojournalist Gives Talk as Part of Arts & Lectures’ ‘Nat Geo’ Series

When I mentioned to photojournalist Lynsey Addario over the phone that I read her memoir, It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War, and found it both stirring and terrifying, she let out a laugh and said, “Aren’t you glad you’re not my mother?” It’s a sobering question considering the life-and-death situations with which Addario is constantly confronted in her job as a war correspondent — she’s been kidnapped twice.

Selfishly, I am glad she chose the path she did, as Addario has documented some of the Middle East’s most pivotal moments of the past decade, from the fall of Saddam Hussein to the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan to the Libyan civil war. What she captures is far more than combat stills — she illuminates the humanity of the men, women, and children living in the battle zones trying to carry on semblances of “normal” existence — going to school, having babies, providing for family, etc. In doing so, Addario reveals that we have far more in common with people of differing cultures than we may have thought.

From her home in London — which she shares with her husband, journalist Paul de Bendern, and their 5-year-old son — Addario spoke about spending time in war zones, the sexism she experiences on the job, and the responsibility she feels to show the world the consequences of our foreign policies.

I find your profession both scary and enviable, to be in the middle of the fray, capturing it so people can understand what’s going on — I imagine there is nothing like it. When I first witnessed what it was like to watch history unfold, I mean, there was no substitute. It’s exhilarating and I started to feel this sense of responsibility immediately because I felt like most Americans who make up the bulk of whatever readership I’m working for don’t get the chance to witness what I witness, so I felt like it’s very important that I’m here and show them what’s happening on the ground. These are the fruits of our foreign policy; this is where our troops are fighting. I felt like it’s really important to be here.

How do you cope with that burden of responsibility? It’s hard because I’m a pretty intense person, and I don’t have an off switch, really. So once I started doing this work, I just felt like there was no end in sight. One of things I always struggle with is that I kind of always want to be in a hundred different places at once. Obviously, that’s not possible, but I never feel like I’m doing enough. I always feel like I’m sort of struggling with [the] need to be doing more.

How do you separate your life at home with your family from your life in war zones? Well, you sort of learn to separate the two worlds and just say, “Okay, when I’m home, this is life. When I’m in the field, this is a different life.” … When I first started out, I was like, wait; why doesn’t anyone care that there’s a war? I still feel like that, but I can’t judge people because most people, they’re preoccupied with just sort of getting by in their own lives. So I think my job is to try and make them care but to not judge them.

You mentioned in your memoir that Sebastião Salgado inspired you to be a photojournalist. I know; it’s funny — I think it was last year — I was in South Sudan and I posted a picture on Instagram, and he “liked” it. It was the highlight of my life. … It was very funny. It was a completely starstruck moment, you know. That’s who I get starstruck over.

You’ve spoken about being a female photographer in war-torn places. It must be disheartening to have men make assessments of your capability — or liability — based on your gender. I think, like, whether or not people admit it, the sexism is incredibly pervasive today in the year 2017. I’ve been doing this job for 23 years, and it still exists. I still have to fight to prove myself in a way that I’m sure my male colleagues don’t, and that is incredibly frustrating. But my philosophy has always been to just get on with it, to just show rather than sit around and complain. To just do the work and to try and do it better than anyone else or to try and do the best I possibly can. It’s not that it’s not frustrating, but it’s just a fact. This is, sadly, how it still is.

They could choose to see you as an ally because you can get access places they can’t, such as into the women’s hospital in Kabul. I think there’s just incredible competition in this job, and there’s a lot of narcissism, as well. I think rather than look at it as a collaborative process, some people look at it as like it’s a zero-sum game, and it’s just not. That’s just not how it is. I’ve been very generous with my contacts and information, and anyone who reaches out to me, I try and help. Everyone’s very different in their approach to this work.

It seems, unfortunately, there’s plenty of war and misery to go around. I guess, but there’s not much money in our profession anymore, so I think people are really struggling for assignments.

You mention in your book that you are a shy person. But to take the photos you take, you have to get right up in the melee. Does being behind the lens embolden you? I started out shy; there was no question I was terrified to photograph people. Now I think it takes a lot for me to be intimidated. I observe a lot when I’m working. I feel like my greatest asset is to be able to just hang out and observe and then figure out how to tell a story. But I also feel like the camera enables me access to places that obviously I would never have access to [otherwise]. I think it’s kind of an excuse to sort of butt into people’s lives. Obviously, why would a complete stranger let me into the delivery room? Or why would a complete stranger let me photograph the funeral of their mother? These are, for me, such great privileges to be able to witness those things. I think also being a woman helps because I think that I’m seen as sort of less threatening, but I also think it’s in the approach. We all have different techniques with how we approach a subject.

What I love about your photos is that you capture people in intimate moments — experiencing loss, birth, fear, family, celebration, war — showing that their lives are similar to our own despite the separation of culture, etc. That’s my point. That’s exactly my goal, to connect these two very different worlds. How can I show that Iraqi women are just like us? Or Syrian women? Sure, they might be refugees, but they’re women, just like us. They want the best for their children. They want a home. They want security. We might have these huge cultural divides, but we’re all the same at the end of the day.

These days feel more frightening than ever, with the philosophy of our president being “use versus them.” Has that changed anything in terms of your job? Maybe makes it more important than ever? It was really disheartening when [Trump] came in and implemented the Muslim ban, for example, because I feel like, “Oh my god, you are basically doing recruitment for ISIS.” … It’s hard for me because I’ve spent the last 17 years in the Middle East and in the Muslim world, and I’ve been treated with such incredible respect and generosity and hospitality, and I think that it’s very easy for people to just label things and people they don’t know. The harder thing is to actually take the time to get to know them.

Have you ever shot a series in the U.S.? I’m working on a story now for National Geographic in the U.S., so I was there most of last month and then I’m coming back on Friday. Actually, I’ll be in Michigan and then Chicago and then I’ll be in New York. So yeah, I’m working on a piece right now.

How do you cope with the long periods of waiting for the action, like when you were in Istanbul biding time until the Iraq invasion? It seems a job of contrasts — durations of down time and then go, go, go. How did you deal with it? So much of international journalism and being a war correspondent or a photographer is waiting. The best stories usually entail a tremendous amount of waiting. I think that that’s something that most people don’t realize, but that is the reality. [You] just have to make sure you’re there when everything goes down, and the only way to do that, because so much of this is unpredictable, is actually just being there and waiting.

What’s the longest you had to wait? [I spent a long time] being in Northern Iraq; I think it was like five weeks sort of basically waiting for the fall of Saddam. We got in there through Iran, but none of us had an exit visa to go back into Iran. We all had a single-entry visa to Iran, and then we couldn’t go south because Saddam Hussein was still in power. None of us had a visa for Iraq, so basically we were stuck. We couldn’t get out until Saddam fell. That’s something that I could do in my twenties and thirties. Now I have a child, and so it’d be a lot harder for me to go into a situation where there was no exit with a 5-year-old because, God forbid, something ever happened to him, I’d need to get out.

And you wouldn’t want anything to happen to you, either, I would think. I guess, but that’s less of an issue … I’m not scared of dying, obviously. I’ve been confronted with that several times. It’s more about I have him to think about more than myself.

You’ve been kidnapped and in other terrifying, life-and-death situations. Were you frightened of dying before then, or do you just become inured to the danger? No photographer or no person who covers war expects to die. It’s not like you go into these situations being like I’m marching to my death, you know. I think it’s just that the possibility is always there. [But] I think there’s no substitute for sort of knowing that it might happen to that feeling when I’m looking down the barrel of a rifle and thinking, “Okay, this is it. I’m about to die.” Obviously that feeling is unbelievably terrifying, and you can’t really put it in words. … When something like being captured happens, that fear is so overwhelming.

That makes sense. I suppose you don’t spend your time constantly worrying about dying because you couldn’t do your job. I mean, of course you’re scared; anyone who covers war feels fear, and if you don’t then you’re crazy. Of course I’m scared when I’m covering war. It’s not like I’m fearless, you know, but I manage it. I put it in a place, and I say, this is rational fear of course if I’m covering war, but this is part of the job.

Is there anything you would like to say about your job or what’s going on in the world today? I think that there’s always this misconception that people who cover war are adrenaline junkies, and I think that the most important thing is to realize that adrenaline has nothing to do [with it for me]. Look, everyone’s different, so everyone has different reasons for covering war. But me personally, and a lot of the great correspondents that I know, don’t do this for the adrenaline. They do it because they believe that the public has the right to know what’s happening and to know about human rights and abuses, to know about the repercussions of our foreign policy. So I think it’s important to dispel that misconception that’s it’s all about the adrenaline.

Are you participating in the film being made by Steven Spielberg and starring Jennifer Lawrence? I’m a consultant, so I’m definitely sort of reading versions of the script, and I’m in touch with Jennifer Lawrence a lot … I took her on assignment with me, and Spielberg is still the director. So and there’s a script — there’s no production date set yet, but yeah, it’s happening, I hope.

How do you feel about having your life story on the screen? I haven’t even really thought about it; it’s not at that point yet. It hasn’t become a reality to me yet.

4·1·1 UCSB Arts & Lectures presents photographer Lynsey Addario as part of its National Geographic Live! Series on Saturday, May 13, 3 p.m., at UCSB’s Campbell Hall. Call 893-3535 or see artsandlectures.sa.ucsb.edu.