David Wiesner at SBMA

Artist Depicts ‘Wordless Storytelling’ Through Timeless Images

Few childhood memories compare to the experience of sharing a well-loved picture book. First, there’s the settling in process, as child and reading partner find a comfortable way to sit that allows both to see the book. From this intimate point of departure, the pair takes off on an imaginative journey that’s guided by whatever is on the page but is certainly not limited to it. The book becomes a point of departure, a place from which child and adult leap together into a world that is as much a place they make as it is one they perceive.

In the impressive new exhibit David Wiesner & the Art of Wordless Storytelling at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA), one of the preeminent figures in contemporary picture book making gets a show that explores the process and the influences behind his powerfully fertile imagination. As the exhibit’s title indicates, Wiesner operates beyond illustration in a territory that’s primarily defined by what can be told through images alone. Among his three Caldecott Award winners, for example, only his sublimely surreal take on the tale of The Three Pigs (2002) employs the traditional composite art of images complemented by words on the page. The other two Caldecott winners, Tuesday (1992) and Flotsam (2007), deliver their stories without recourse to written language.

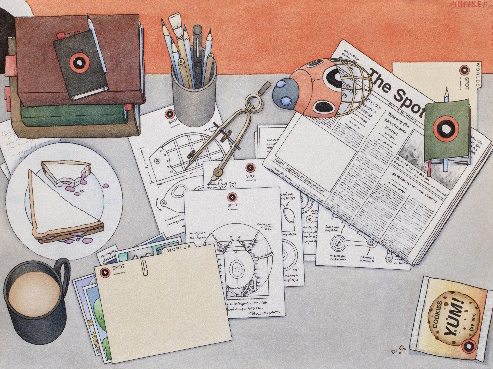

A graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design and a prolific artist in multiple media since early childhood, Wiesner blends the wide-eyed enthusiasm of a kid who loves comic books with the educated sensibility of an art historian and the craftsmanship of a technical illustrator or a precisionist painter. His heroes include Charles Sheeler and Salvador Dalí, but he also learned a lot from the artists at DC Comics and from Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng, the animators behind Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and the Road Runner.

In practice, Wiesner often harnesses his command of technique and delight in intricate detail to ideas that resist or even shatter the fourth wall of the conventional picture plane. His version of The Three Pigs offers a particularly bold example of this tendency. In the opening pages, the wolf pursues the first of his victims, the pig who builds his house with straw, until we reach the standard and, for the pig at least, catastrophic first plot point, when the wolf’s huffing and puffing ordinarily results in a blown-down house and an eaten-up pig.

That’s not how things go in Wiesner’s version, however. His straw-house pig scrambles across the edge of the picture frame and escapes the wolf by exiting the representational schema in which he originated. The technical execution of straw pig’s transition is dazzling and adds an irreducible element of visual pleasure to the conceit. Inside the old frame, where the wolf lives, the pig’s hind end is flat and strongly bounded by a dark black line. Outside the frame, the rest of his piggy body is rounded, textured, and deliciously fleshy. Over the course of the next dozen page turns (the page turn being the fundamental discursive unit of the picture book), the three pigs take a merry jaunt through a surreal space that’s neither in nor entirely out of the book. The image of three giddy pigs flying on a paper airplane that’s been folded out of a page from the book they are in has an M.C. Escher–like audacity, but the blank pages that follow go where even Escher feared to tread.

I fear I have overemphasized what’s clever about the work at the expense of its extreme charm and vitality. There is one certain corrective, and I recommend it to everyone. Get to the SBMA (1130 State St.) for the David Wiesner show, and if you really want to enjoy it, take some children. They will show you how wordless storytelling works and what fun it can be.

David Wiesner & the Art of Wordless Storytelling shows through May 14.