Superintendent David Cash Makes His Mark

After One Year on the Job, the District Gets Reshaped and Reinvigorated

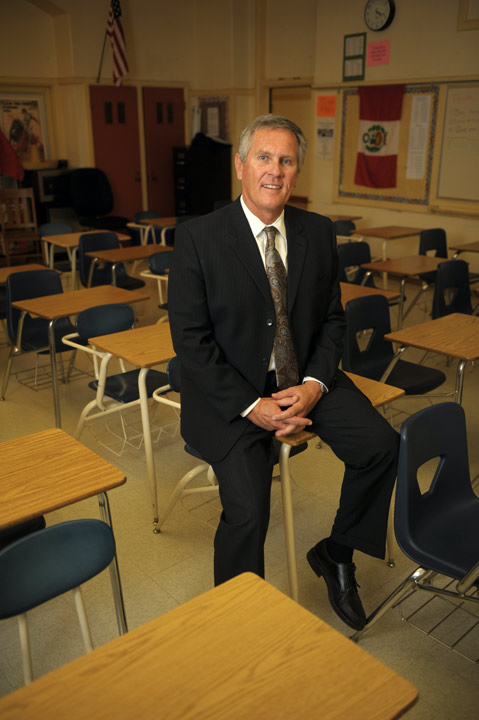

David Cash skipped the 2nd grade, not because he was a prodigy, but because none of the 2nd grade teachers at his elementary school wanted him in their classroom. “I was a wiggly kid,” Cash described himself. Some parents who have interacted with the Santa Barbara Unified superintendent have guessed that he suffers from ADHD. He’s never been diagnosed, but he admits that, even now, he isn’t one to sit behind a desk. As superintendent, he constantly visits school sites — including every classroom in the district twice a year — and when he’s at the district headquarters, he’d rather trot across the courtyard to a colleague’s office than pick up the phone.

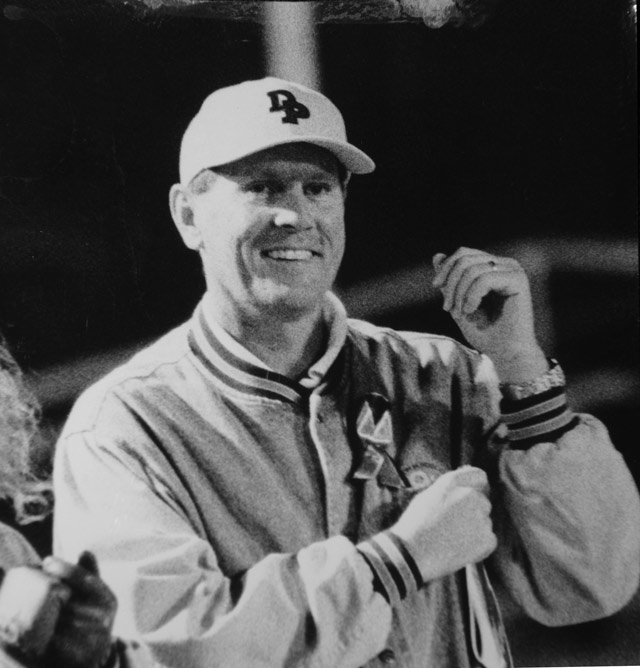

Cash’s career has moved at a frenetic pace, as well. After graduating from UCSB in 1979, he attended law school at Willamette University and then worked as an attorney in Portland, Oregon. But five or six years into his career, he had an epiphany. While lecturing to a high school class on the First Amendment, he decided he could do more good as an educator. So he left the law and began teaching high school social studies in Irvine, near his hometown of Long Beach, then returned to Santa Barbara as a special-education teacher at Peabody Elementary School, where Paul Cordeiro was the principal. Cordeiro, the current Carpinteria Unified School District superintendent, urged him to consider working as a school administrator. Cash did. After completing a degree in administration at UCSB, he became principal of Buellton’s K-8 school. Three years later, he returned to the Santa Barbara District as a principal first at Goleta Valley Junior High and then Dos Pueblos High School. In 2004, he left for Fullerton to become an assistant superintendent, left there in 2006 to take over as Claremont’s superintendent of schools, and, three years later, took on the challenge of running the large Clovis school district in Fresno.

In retrospect, Clovis seems a terrible fit for Cash. Located in a well-heeled, ultra-conservative section of Fresno, folks there honor what they call “The Clovis Way.” The schools enforce a strict dress code, the playing fields are hallowed grounds, the teachers are not unionized, and an abstinence-only curriculum passes for sex ed. Just two weeks ago, some parents sued Clovis for allegedly violating California law by teaching misinformation about contraception and, while doing so, using a textbook that lists getting plenty of rest and respecting yourself as methods for avoiding STDs, according to a press release issued by the ACLU.

Cash, a registered Democrat, had quickly lost clout with the Clovis community when his board expelled a popular high school wrestler who performed what The Fresno Bee called an “aggressive move” on a teammate. The expelled wrestler said he was employing a common maneuver called a “butt drag,” but his accuser said the alleged bully had been, in wrestling parlance, “checking the oil.” It didn’t help Cash’s relationship with his colleagues when, in response to budget cuts, he called for an across-the-board cut for all teachers and administrators. So it should have come as no surprise that in 2011, the board of education summoned him to undergo what promised to be an intense evaluation. What did come as a surprise to everyone was that Cash never showed up. Instead he announced his resignation. After a stellar career marked by speedy advancement and visionary ambitions, Cash had incredibly, unbelievably, decided to quit. He was retiring from education and moving to Monterey.

Above and beyond the culture clash at Clovis, Cash, 57, said his weariness resulted primarily from the fact that four of his closest friends had all died within the year. And so he was ready to catch his breath, to spend more time with his family, and to finally quit his wiggling.

Doctor Yes

The deus ex machina arrived, however, in the form of a casual email. Just after the deadline to apply for the Santa Barbara superintendent position had closed, the outgoing superintendent, Brian Sarvis, sent out word that Cash had announced his retirement. That email set the wheels in motion. A member of the district’s search team, Rudy Castruita, happened to be Cash’s dissertation director when he received his 2008 EdD in Educational Leadership at the University of Southern California. Castruita recommended that the board check out Cash’s résumé. Since Cash had been named a potential candidate early on in the search process, they agreed. According to Trustee Ed Heron (who had not met Cash before), it was clear he was the man for the job once he interviewed.

For Cash, a man who was determined to retire, Santa Barbara was the only place that could lure him back to work. His wife, Heather, was raised here, and their two children were born at Cottage Hospital. This would be his very last job. Still, in the year he has taken over as superintendent of the Santa Barbara Unified School District, there has been no sign that he is slowing down.

Since arriving, Cash has completely overhauled the district office staff and reassigned many of the principals to different schools. He has drafted a “Strategic Plan” for the district, sold it to parents and teachers at public forums, and begun the process of systematically integrating technology into classrooms. Todd Ryckman, former Dos Pueblos teacher and current district director of technology, said that with Cash “change is fast and furious. People who don’t like Dave don’t feel comfortable with change.”

When Cash took over Dos Pueblos in 1999, he tabbed Ryckman and some of his other tech-savvy teachers to build a digital infrastructure at the high school. Dos Pueblos became one of the first schools in the district to manage its own mail server. This was so successful that the then superintendent Michael Caston made the server part of a district-wide system. When DP moved to Gmail, the district once again followed suit. An early adopter of digital grade books and one of the first schools to post grades online, Dos Pueblos set up file servers early on so teachers could easily share lesson plans and documents by dragging and dropping. Although Cash wrote grants to fund the equipment and manpower necessary to make all of that possible, and although several Dos Pueblos veterans remember him for rescuing them from the analog age, Cash insists that he is not at all technologically inclined. But he couldn’t ignore the fact that kids are growing up in a wired world.

Cash’s willingness to delegate authority and then to empower his delegates is a recurring theme. School board president Susan Christol Deacon said, “When he first came back to the district, he told principals, your job is to say yes.” Deacon participated in the parent-led effort to install a new pool at Dos Pueblos that began while Cash was principal. The school district only approved $700,000 for the project, which would cost millions, but Cash told the school’s parents to go ahead and raise funds on their own. They did. Longtime Dos Pueblos economics teacher Roland Lewin said, “If you go to him and tell him, ‘I’ve got this idea,’ he’ll find a way to get you what you need so that you can be successful. I call him Doctor Yes.”

What Is a Superintendent?

A school superintendent is often referred to as the CEO of a district. While keeping a balanced budget is a crucial part of the job, the business analogy tends to break down. Schools aren’t for-profit enterprises; their raison d’être is to educate children, not reap profits. Administrators must divide their attention between the logistical operations of their districts and the performance of their students.

It’s a bit more complicated than that, though. Longtime district teacher and administrator Mike Couch said that a principal has four bosses — teachers, parents, students, and the district. A superintendent, he said, has a fifth boss — the community. Fullerton high school superintendent George Giokaris, Cash’s boss from 2004-2006, explained that on top of pleasing all of those constituencies, supes must also navigate the minefield of politics.

Cash’s dissertation, completed in 2008, offers a window into his theory of executive power in school districts. It focuses on the relationship between superintendents and principals. In it, he elaborated on a concept called “defined autonomy,” which he defined as “the relationship school principals have with superintendents where non-negotiable goals in teaching and learning are given to schools, but schools are given the responsibility and authority to determine how best to meet those goals.”

In other words, the superintendent gives his or her principals plenty of leeway in how to spend their resources and run their sites, but they are held accountable to specific, concrete goals. This means that a superintendent should, according to Cash, meet regularly with principals one-on-one. And on the spectrum from manager to educator, Cash argues that superintendents must lean toward educator. In their meetings with principals, they must discuss metrics-based student achievement and instructional strategies. So, while on the one hand, Cash gives his principals lots of rein, on the other hand, he pays close attention to what’s happening at their schools.

And whereas he is often willing to delegate responsibility, one area where he inserts himself is in the teacher hiring process. The single most important thing a school can do to improve achievement, he said, is to hire good teachers. This year, for the first time, Santa Barbara teacher applicants were asked back for second interviews where they presented a sample lesson plan. Cash observed most of them.

And he is a workhorse. “When I used to show up to school early,” said Ryckman, “Dave was already there. When I left late, he was there. When I went to my classroom on the weekend, he was there.” The principal’s assistant at Dos Pueblos, Marietta Sanchez, said that her desk would often be stacked with work on Monday mornings because Cash had spent all weekend in his office. Now, he said, 60- to 80-hour work weeks are short.

Honeymoon’s Over

If you speak to Cash one-on-one, you’ll likely find him warm and affable. But Doctor Yes can be intimidating, too. Barrel-chested, six feet tall, supremely confident, and blessed with a subwoofer of a diaphragm, Cash does not present meekly. Board Trustee Monique Limón described him as “a direct and straightforward person.” Associates have made comments like, “he’s not out to make friends” or “he’s willing to break a few eggs.”

Cash agrees. “The stakes are too high,” he said about student success, to worry about pleasing every employee or even every parent. “The people who are going to be upset are the adults.” And his actions so far have indicated that, although he was once a labor attorney, he’s not afraid to test the authority of the unions. His loyal fans, of which there are many, cast him as a motivator more than an egg-breaker. “My goal,” said Cash, “is to get people to do things they previously imagined they couldn’t do.”

His fans are also extremely loyal. One of his assistant superintendents uprooted herself from Green Bay, Wisconsin, to work for him, and another one followed him from Clovis. Sanchez said that he’s one of her “favorite people.” Jim Ranta, who coached water polo and taught math at Dos Pueblos for 40 years, said Cash was one of his two best principals (the other being Couch). Former employees say that he had an open-door policy and always listened to input from others. Cash said the greatest lesson he learned from his mentor, former Santa Barbara superintendent Michael Caston, is “you can find a common ground even with people who seemingly hate you, vehemently oppose you.”

About Cash, Giokaris said, “He combines his passion with his political astuteness, his situational awareness, his intelligence, and then his ability to have a vision and see the larger picture.” It’s a gooey hot fudge sundae of a compliment, but many agree with it. Multiple district employees have called Cash a “visionary.” “He sees schools in a global sense as opposed to subcommunities in the city,” said his new lieutenant and former McKinley Elementary principal Emilio Handall. One innovative technique Cash has brought to the district to increase uniformity is a program where school administrators visit one another’s campus to compare the differences in the way they meet their specific challenges. Santa Barbara High School principal John Becchio said that the district feels much more cohesive under Cash. “In the past, it’s been really fractured, everyone in their own school doing their own thing.”

Healing those fractures, reasons Cash, will go a long way to improving Santa Barbara’s schools. And improving achievement across the board will hopefully help erase the glaring achievement gap between whites and Latinos that is literally visible in segregated elementary schools and stratified high schools. Right now, he said, parents have an easy excuse to request a transfer out of their neighborhood school.

Adding to Cash’s challenge is the financial state of public education. With the current fiscal reality in California — Santa Barbara schools have suffered more than $20 million in cuts in just the past five years — classrooms are brimming, courses are on the chopping block, and the district is asking its citizens to pick up the tab with parcel taxes. Under those circumstances, it’s hard for a schools boss to look like a good guy.

At the same time, the educational landscape in the U.S. is shifting. Scholars are rethinking how to assess students and hold teachers accountable. The federal government is exploiting its pocketbook to urge reform at the state level. Mobile, networked technology is transforming the classroom. And social entrepreneurs are strengthening the connections between schools and their communities. Paradoxically, as resources are shrinking, innovation is accelerating. “For me, Cash said, “it feels like one of those seminal moments in education history.” If Cash can resist his lifelong urge to wiggle, he might just make Santa Barbara part of that history and his tenure here his legacy.