Submarine Shelling of Ellwood Oil Field in 1942

Myths Can Obscure Consequences of 70-Year-Old Event

Less than three months after the Imperial Japanese Navy attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the United States into World War II, a Goleta oil field became an early, and unexpected, target in that horrendous conflict.

February 23, 2012, will mark 70 years since a large Japanese submarine, identified as the I-17, surfaced at sundown off Ellwood Mesa and fired its deck cannon at the tidelands oil-production facilities clustered along the shore. Aerial photos from the time show more than a dozen piers anchored to what is now Haskell’s Beach.

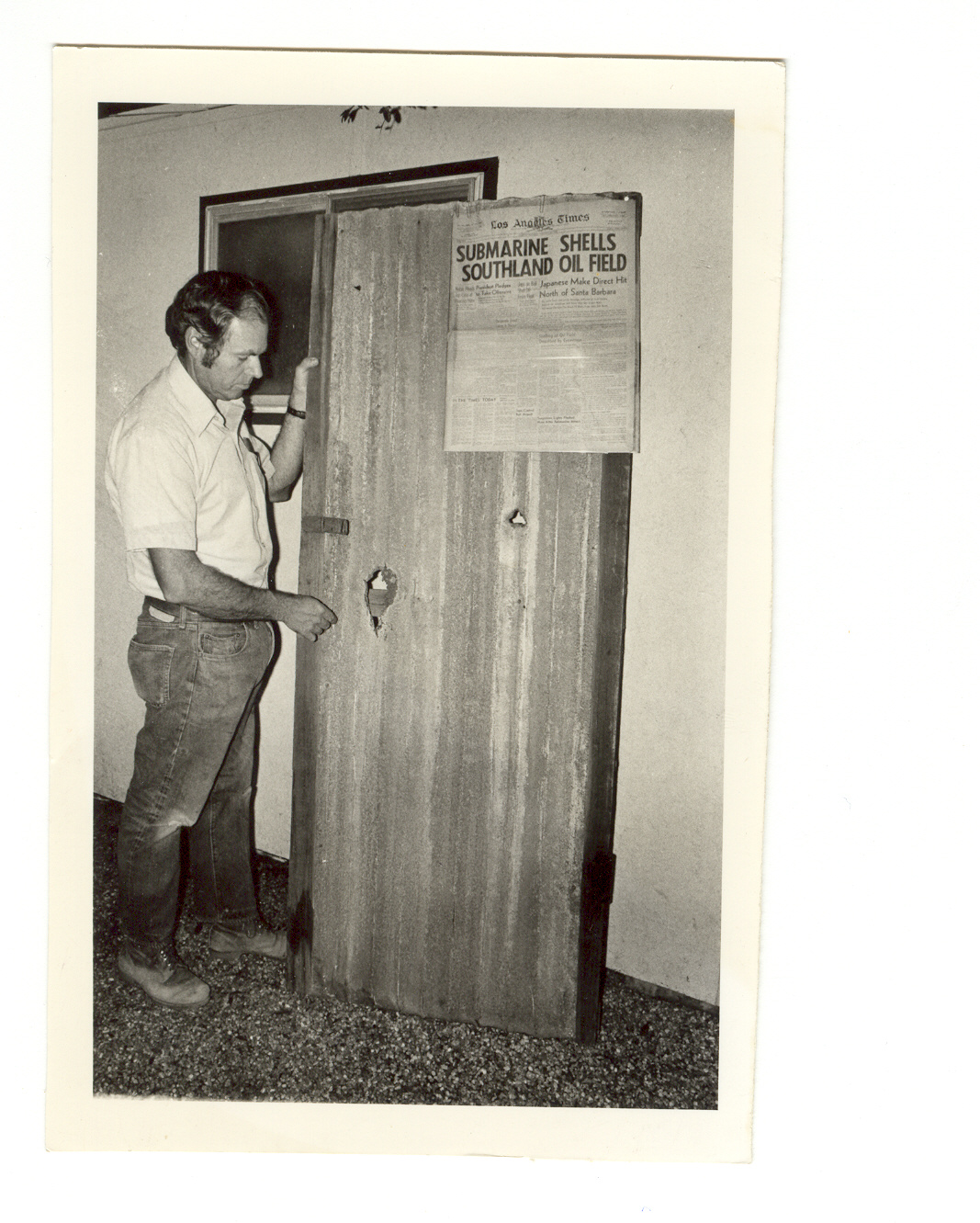

Given eyewitness reports that the sub was within a mile of shore, and the profusion of oil storage tanks, piers, and pump houses, the damage was remarkably minimal: an estimated $500 worth of splintered railing, cracked equipment housing, pier planking, and shrapnel-punched doors. Duration of the attack was estimated to be around 20 minutes, though the vessel was sighted in the Santa Barbara Channel an hour after the attack began.

The Ellwood shelling was, in the words of Kenneth Hough, a PhD candidate in UC Santa Barbara’s History Department, “deliberate, almost leisurely.” It was also said to be the first attack on the U.S. mainland by a hostile nation since the sack of Washington, D.C., in the War of 1812.

Well, maybe not. As part of Hough’s research into Americans’ fears regarding Japan in the pre-World War II era, he unearthed earlier incidents of brief military attacks on the U.S. One was a border incursion during the Mexican-American War of 1846 and the other a submarine attack on a barge in a Cape Cod harbor in 1918 during WWI.

However, the event was, as the Santa Barbara News-Press headlined on February 24, 1942, the “First Attack of War on Continental U.S.” Fortunately the raid produced no human casualties, though one soldier was injured trying to defuse one of the “dud” shells.

While facts are hard to pin down — even the number of cannon shots varies widely — myths and speculation seem to cling to the Ellwood shelling like burrs to a hiker. Some claimed that signal lights had been seen in the Goleta foothills before and after the attack; others, at least initially, thought the inept shelling a hoax staged by the American government to rally citizens behind the war effort and to sell bonds.

One persistent story is that the sub’s commander, Kozo Nishino, targeted Ellwood to avenge a loss of face he allegedly suffered at the hands of oil workers when he captained an oil tanker that loaded at pre-war Ellwood. That linkage is suspect, to say the least.

The earliest version of this “revenge” motive I’ve found is in Santa Barbara’s Royal Rancho, published in 1960 by the late S.B.-area historian Walker Tompkins; it has been repeated elsewhere. However, in 1993, military historian Harvey Beigel reported that the I-17 was originally ordered to wage terror attacks on West Coast population centers.

Nishino found San Francisco and San Diego “too well defended and so he chose the Ellwood oil fields,” Beigel wrote. The I-17’s poor gunnery was likely due to the crew’s haste and what the author termed the deck gun’s inadequate range-finding and targeting mechanisms.

Santa Barbara-area historians, such as Tompkins and Justin Ruhge, should be credited for laying the groundwork, but as researchers expose new information, skeptics like Hough need to be heard. A good example of fear clouding the facts were the reports of “signal lights” from a supposed fifth column of Japanese agents guiding the I-17’s attack.

Though naval intelligence did find activity by so-called “Japanese war societies” in Santa Maria and Lompoc, no connection to the I-17 attack was ever made, according to a 1965 letter to Tompkins from the Santa Barbara-based Navy liaison. A better explanation of any strange lights above Ellwood came in a 1988 article written by J.J. Hollister III about his illustrious family for the Santa Barbara Historical Society.

In it, Hollister disclosed for the first time that his father, John James Jr., had taken the family van from their Winchester Canyon home to investigate the flashes and booms at sea that night. Due to blackout requirements only the parking lights were on as the vehicle slowly traversed the rough road’s many dips and turns. From far below, the sporadically seen lights could seem to be signals.

“Thus it was that Jack Hollister contributed in a small way to the groundswell of rumor and fright,” Hollister wrote, “that resulted in President Roosevelt signing an executive order … that forcibly removed some 117,000 Japanese from their homes to inland detention camps.” Most of these people were American citizens.

Myths and how they come to be are of interest to historians, and they should be to journalists who may be the first to disseminate them. The Ellwood shelling, moreover, demonstrates how some myths can cloak deeper cultural attitudes that may lead to damaging actions.