On the Road – The Great Plains

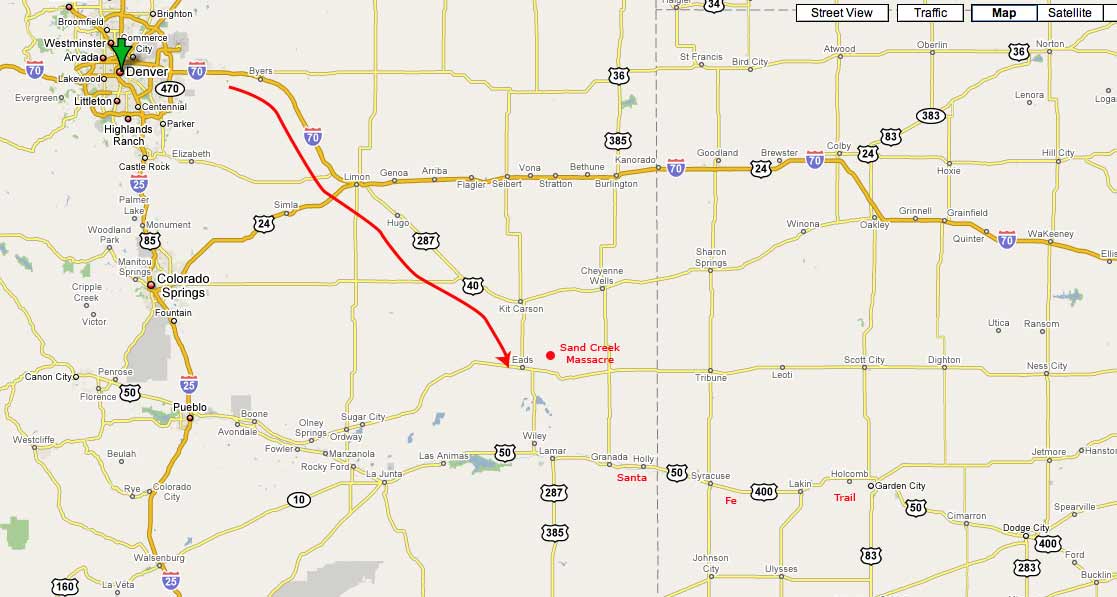

Heading east out of Denver, the sun was shining overhead but ahead of me, out on the Plains I could see the clouds building. Snow was ahead of me. It was time to turn south and drop below the worst of it.

East of Denver the landscape changes dramatically, shifting from mountainscapes to a sort of barren tundra-like environment. This marks the beginning of prairies and a thousand miles of wide open spaces marked by a relatively flat landscape perfect for growing corn, wheat and other staple crops further to the east.

There are few trees and what looks like a scruffy grass, perhaps edible by buffalo in centuries past but a tough place to make a living for farmers or ranchers I would guess. The wind howls and though I’ve still got fifteen-to-twenty miles of visibility, as I eat up the miles on Highway 70, the sky is dropping down on me rapidly, a fog like cloud cover.

I’d originally planned on heading north up into the Black Hills of South Dakota but the snow storms that have been creeping up on me the past several days have scotched those plans and now the weather ahead is causing me to shift my plans again. Stopping at a rest area I re-check the maps. Not too far east of my position at the small town of Limon, State Highway 287 cuts down and across the lower part of Colorado. This route will take me across the lower part of Kansas and the Weather Channel promises me that this is well below the snow line.

As it turns out, Highway 287 cuts through historic country that takes me through some of our country’s frontier past – both the best and the worst of it. I cruise through Wild Horse and Kit Carson. Wild Horse has a post office, church, a scattering of buildings that have known better times and not much else. Kit Carson is a bit larger but not much. Founded in 1838, and at one time the western end for the Union Pacific Railroad, Kit Carson’s was ideally located to serve as a commercial trade center. The development of modern roads, the interstates and the trucking industry have left the town much smaller, quieter and less prosperous.

I continue on to another small town, this one named Eads. I’ve dropped far enough south that I’m out of the worst of the snow and the visibility is much better. I stop for breakfast at a small cafe called the Ranch House. The wind is still gusting enough that I’m chilled to the bone by the time I reach the front door: the temperature is in the low 30s and the wind blowing at 30-to-40 mph. Inside, though, it’s warm and toasty.

It’s a cowboy cafe. The Marlboro man would be comfortable here. A sign on the wall says, “First thing when you get up in the morning, put on your Stetson.” Just then several young men, all decked out in hats come in. “It’s a bit nippy out, ain’t it,” one of them remarks. With the wind cutting through me like a breeze through an open door any time I get out of my truck, I agree wholeheartedly.

Another sign on the wall says “Never kick a fresh turd on a hot day.” Today it’s cold enough to stub a toe on that turd. After a huge breakfast of hot cakes, coffee and orange juice I venture outside. it’s still way too cold. An Econo Lodge is just across the street. On the off change I can get an wireless connection I power up my laptop. Bingo – I can connect via the motel’s router. Amazing. Not much more than a century ago this was rough, wild country with few roads, a handful of saddle tough pioneers and almost no connection to the outside world and now I’ve got it at my fingertip.

Big Sandy Creek is just a few miles up the road, the site of what in now known as the Sand Creek Massacre. A chapter of our history that has not brought out the best of us. As I turn on to the dirt track that leads to the national historic park where the massacre occurred I’m surprised at the sign – which says 55 mph. I’ve never driven a dirt road with a legal speed limit that matches the nearby state highways. I can see why though. The road is wide and straight as most all of the plains state roads are having been surveyed out along lines of latitude and longitude prior to the homestead days.

The Big Sandy isn’t much, more a depression in what is rolling grass-covered country, perhaps a much larger creek in 1864 when Colonel John Chivington ordered his troops to attack the encampment of a band of Southern Cheyenne chief Black Kettle. Despite the entreaties of one officer, Captain Silas Soule, who refused to follow Chivington’s order and told his men to hold fire, other soldiers in Chivington’s force immediately attacked the village.

Looking out at what is a bitterly cold but overwhelmingly peaceful view, it is difficult to imagine such a scene playing out here and the impact it had on our western history. Resulting in a heavy loss of life, the Sand Creek Massacre devastated the Cheyenne’s traditional government, due to the deaths at Sand Creek of eight of 44 members of its governing council, including White Antelope, One Eye, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, Bear Man, War Bonnet, Spotted Crow, and Bear Robe. Among the chiefs killed were most of those who had advocated peace with white settlers and the U.S. government.

Ironically, not only did Black Kettle survive the slaughter but he continued to work towards a peaceful resolution of the conflict. Just three years later, in 1867 signed the Medicine Lodge Treaty, agreeing to move to two smaller reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) where the Cheyenne would receive annual provisions of food and supplies. When the promises were not kept, more warlike Indians began a series of raids that prompted a swift response.

Under General Philip Sheridan, three columns of troops converged to launch a winter campaign against Cheyenne encampments, with the Seventh Cavalry commanded by George Armstrong Custer selected to take the lead. Setting out in a snowstorm, Custer followed the tracks of a small raiding party to a Cheyenne village on the Washita River, where he ordered an attack at dawn. It was Black Kettle’s village, well within the boundaries of the Cheyenne reservation and with a white flag flying above the chief’s own tipi.

Nonetheless, on November 27, 1868, nearly four years to the day after Sand Creek, Custer’s troops charged, and this time Black Kettle could not escape.

“Both the chief and his wife fell at the river bank riddled with bullets,” one witness reported, “the soldiers rode right over Black Kettle and his wife and their horse as they lay dead on the ground, and their bodies were all splashed with mud by the charging soldiers.”

Custer later reported that an Osage guide took Black Kettle’s scalp. On the Washita, the Cheyenne’s hopes of sustaining themselves as an independent people died as well; by 1869, they had been driven from the plains and confined to reservations.*

I’m out here alone on these plains. It’s not only too cold to attract other visitors but the park is still closed for the winter so there are no guides to walk me around and explain more of this sad chapter in our history. I suppose I’m comforted a bit by the fact that just a few years after this Custer would receive his own just rewards.

With a final glance behind me I move on, back down the dirt road to Eads and on down Highway 287 to Granada. On the way into town I spot my first tall structures that marks wheat and corn country – the cooperative silos that stand eight or so stories high.

The stain of this morning’s experience will no wash away easily. Later that day when I reach the evening’s motel I first hear about the controversy regarding the Reverend Jeremiah Wright’s sermons. The words are repeated over and over, no matter which of the cable news outlets I turn to.

“God Bless America,” he first says.

Then “No, no, no, God damn America, that’s in the Bible for killing innocent people … God damn America for treating our citizens as less than human. God damn America for as long as she acts like she is God and she is supreme.”

People are aghast at the words and it appears for Barack Obama they might threaten his presidential ambitions. I wonder about them, though, as I reflect on what I’ve learned today about America’s past today.

*As noted in a PBS special entitled “New Perspectives on the West”.