The KCSBeat

The Man Steps In: a Brief History of KCSB, Part II

Before we march bravely on into the annals of KCSB history, we should note that, of the few widely-known facts about the station’s past, one pops out above the rest: that it was the first and is thus far the only radio station to have been forcibly shut down by the cops.

In the small world of community, college, and renegade freeform broadcasters, this designation confers massive amount of credibility. But how did it actually happen? What outlandish conditions could possibly have mounted up to lead to the mandated shutdown of an innocuous 180-watt station staffed primarily by beachgoing college students of the early 1970s?

Perhaps a little context. By the end of 1969, KCSB had moved once again, this time to its current spot in the then-newly-constructed Storke Communications Building. This location, directly under the iconic Storke Tower, effectively made the station the easiest department to find on campus, and has acted as a boon ever since to sleepy, disoriented new DJs working the graveyard shifts. For concentrations of students across America and Western Europe, the late 1960s was a troubled but exciting era, infused with the ambitious, if quixotic, mood of fomenting revolutions in education, commerce, and society itself. With its own critical mass of college types, filled with flavors of anger political and otherwise, Isla Vista was no exception.

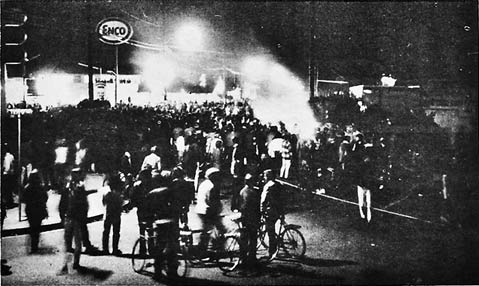

Dedicated KCSB listeners will almost certainly have heard the station’s many remembrances and commemorations of the series of riots sparked in Isla Vista as the 1970s dawned. The destruction of February 25, 1970 undoubtedly seared itself into local memory more deeply than any of the other troubles. The sequence of events, as has already been examined countless times in film, book, journalism, and radio, went down as follows:

“Chicago Seven” defense attorney William Kunstler gave a speech in Harder Stadium. Though not, it seems, an incitement to violence, Kunstler’s talk referenced the controversial firing of UCSB anthropology professor Bill Allen and a recent spate of incidents of vandalism in Isla Vista. KCSB’s own recording of the speech captures Kunstler refusing to endorse these sorts of violent tactics, but also refusing to condemn them.

As night approached, a somewhat confusing chain of events progressed: Police mistook a wine-carrying former UCSB student for a Molotov cocktail-wielding agitator; a passing crowd already primed to rally witnessed this fellow’s arrest; large-scale stone-throwing began; the stone-throwers’ aim angled over toward the Bank of America building, that symbol of American capitalism. Suffice it to say that by the next morning, only tear gas residue and a charred bank foundation remained. Some ruefully recall this as the night that local law enforcement displayed the brazen temerity to force KCSB, a bastion of Isla Vista broadcast journalism, off the air, at perhaps the time when its coverage was needed most.

There’s only one problem with that story: KCSB wasn’t shut down the night the bank burned town, though it was the night of an attempted re-burning of the rebuilt bank. The Isla Vista disturbances of 1970 actually consisted of three separate riots, known as “IV I,” “IV II,” and “IV III.”

The fall of the Bank of America happened during only the first act, IV I. It wasn’t until IV II, an even uglier situation which began the evening of April 17, that KCSB’s ability to cover the action was compromised. Three on-site KCSB reporters, strategically placed in nearby buildings and connected back to the station’s control room by telephone, relayed in real time the events leading to the shooting death of student Kevin Moran. Describing the fire’s spread through the new Bank of America and an attempt by several men to extinguish it, the correspondents remained on the line as both the police presence and the clouds of tear gas spread and intensified.

Despite these valiant efforts to disseminate information about the riot, KCSB could only do so much before the law cracked down. In the wee hours of April 18, the station received orders to cease transmission. Acting through the Chancellor’s office, the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Department demanded the shutdown of KCSB as an ostensible move against alleged “aiding and abetting” of the demonstrations on the part of its reporters. For the next three hours, KCSB complied with this order that directly violated federal law, its frequency carrying only silence.

Whether you regard the early 1970s as a lost era of noble student activism or a terrifying, chaotic time best forgotten, there’s no question about its historical richness, especially with regard to the role of community media. Though the details aren’t always remembered with impeccable precision, KCSB’s importance during the Isla Vista riots is well-known-and as my research is revealing, it’s only the tip of the iceberg as far as the interesting happenings KCSB history. But the radio station’s role during time is always worth another look back: After all, it gives credence to KCSB’s familiar streetwise, battle-hardened, tough-as-nails attitude.