Visionary Vintner

Richard Sanford’s Rise to Winemaking Royalty

On October 28, 2005, at Mission La Purísima de la Concepción, a couple hundred people came together inside the adobe walls of the centuries-old church to sit at one long, wooden table, with only flickering candles to light the scene. There was plenty for us to be excited about on the menu that evening — pumpkin soup with smoked boar, wine-splashed quail with oregano, roasted lamb with truffle tamales — and we all buzzed about the soon-to-be unveiled bottles of pinot grigio, chardonnay, and pinot noir from the brand-new Alma Rosa Winery.

But the real reason so many had converged on the outskirts of Lompoc that crisp autumn night was for a man, not a meal. This was the first time that Santa Barbara’s wine country was celebrating the creation of the Sta. Rita Hills appellation, which had been federally recognized four years earlier, and we’d come to honor Richard Sanford, the man who proved that pinot noir grapes could thrive in that fog-enshrouded, windswept western end of the Santa Ynez Valley.

Today, the Sta. Rita Hills are considered one of the best places on the planet to grow the delicate, delectable grape; pinot is one of California’s most sought after varietals; and the wine business has become one of the most important industries on the entire West Coast. But Sanford’s impact was wider still: Since 1983, he’d been growing his grapes organically, forging what he calls a “new paradigm in agriculture,” decades before sustainability was in vogue. In this one-of-a-kind setting — that candlelit affair in La Purísima church hadn’t happened before and hasn’t since — we all took part in a royal roast of the one-of-a-kind Sanford, a true living legend.

“That was really the beginning of him recognizing what impact his choices have made on the region,” recalled his daughter, Blakeney Sanford, who remembered “giggling a lot” that afternoon with her father as they got ready because being placed atop a pedestal was never part of his plan. “It’s still hitting him. He’s going, ‘Whoa, it’s pretty amazing to be a pioneer.’”

The accolades haven’t ceased, and this past February, Sanford was the first person from the entire Central Coast of California to be inducted into the Vintners Hall of Fame, joining a list of about 40 mostly deceased men and women from the wine world’s history books. Longtime journalist Steve Heimoff, who writes for Wine Enthusiast and is one of the 75 experts polled for Hall of Fame nominees each year, credited Sanford both for pinot’s popularity and the rise of the Sta. Rita Hills. “Either one of those would have made him a very important historical figure,” said Heimoff. “Both of them together make him over-the-top historical.”

In agreement is James Laube of the Wine Spectator, one of the industry’s top critics. “His legacy will always be being the first and having the courage to go forward,” said Laube, but he also praised the quality of Sanford’s wine, having tried every pinot that Sanford’s been involved with over the years, from the first in 1976 to the new Alma Rosa wines. “They age beautifully. They were fantastic. They were as good as any wines anywhere.”

But Sanford’s legacy is not all sunshine. His entire career has been a struggle — economically, emotionally, psychologically — and his lofty dreams have exploded into nightmares more than once. Perhaps that’s why, when you mention Sanford to younger winemakers in the region, you get a curious response. There’s genuine reverence for the man who literally planted the roots of an industry that now employs hundreds, but there is also a silent sense of reservation, because Sanford’s turbulent career isn’t necessarily one that anyone would choose to endure.

Indeed, our October 2005 tribute came just months after Sanford experienced his most devastating blow yet: After building one of the most amazing wineries on the planet, an adobe cathedral of his dreams, Sanford lost it all in a financial disaster and was forced to walk away from his vineyards, his winery, his very name. As we sipped on the debut bottles of Alma Rosa wine, his first project since losing Sanford Winery, it seemed to me like wine country was giving Sanford one big ceremonial slap on the back, collectively saying, “You’ll get ’em next time.” Despite four decades of dedication, Sanford didn’t yet have the option of riding his horse off into the sunset. Instead, his toughest days seemed before him.

“This has been our livelihood,” said his wife and business partner, Thekla Sanford. “It’s offered us an incredible life, even though it’s been challenging. But anything that’s good in life is challenging, and you’re supposed to learn from each thing.” She admits it’s been a “roller coaster” of a life financially, but explained, “Richard is a dreamer. Richard doesn’t give up. He did it because it seemed like the right thing, and it’s what felt really good to him.”

Sailor, Soldier, Rebel, Rascal

Sanford was born on the Hawaiian island of Oahu in March 1941, the son of a naval officer. Nine months later, Japanese warplanes flew directly over their home on their way to blow up Pearl Harbor. While his father fought the war in the Pacific, the rest of the Sanford family relocated to California, first to a Baldwin Hills apartment and then to a home in Rolling Hills overlooking the garbanzo fields of Portuguese Bend on the Palos Verdes Peninsula.

When Sanford was 9 years old, tragedy struck: His father, who survived World War II, was on board the Korean War–bound ship Benevolence outside the San Francisco Bay when a freighter tore through thick fog and rammed the ship, sinking it almost immediately. His dad’s body survived, but his mind was lost. “He was never quite the same,” said Sanford. “I sort of lost him at that stage of my life.” The family’s resources went to taking care of his father, so from the time Sanford was a boy, he was pretty much on his own. Two decades later in 1970, the same year that Richard started growing grapevines, his father committed suicide.

As a student at El Segundo High, Sanford spent his free time lifeguarding, sailing, and, to make money for college, working for the merchant marine. He first studied geology at UCSB but realized he was “more interested in the human interaction with the physical environment.” That meant geography, and since UCSB didn’t offer those courses, Sanford transferred to UC Berkeley.

Graduation in 1965 was followed by service in the U.S. Navy, where he worked as a navigator on a destroyer that shelled the North Vietnamese coastline as part of Operation Sea Dragon. “The whole thing was pretty stupid,” said Sanford, who was discharged in 1968. “I sailed down the coast of Vietnam in tears because it was so wrong for us to be there.”

As an officer, Sanford wrote his own ticket home, hitching rides on military courier planes while seeing the world. His most memorable stop was the Kathmandu Valley, just a year after the king of Nepal opened the borders. “It was like stepping back into the Middle Ages,” said Sanford. “That was a really impressionable time for me. I was on my own spiritual quest, so it was meaningful to be there.”

The trip was also Sanford’s personal rebellion against the American machine that had sent him to kill the Vietnamese but then spat on soldiers when they came home. “My way of dealing was to reject the culture — completely,” said Sanford, “and what an opportunity to have a clean slate to start over.”

Once back in California, Sanford sailed competitively in Santa Barbara on The Rascal, a boat owned by Bill Wilson, who later founded Wilson’s Furniture. They entered a few transpacific races to Hawai‘i and even won a race to Tahiti. “It was through sailing that I ultimately was introduced to people who might be interested in investing in [the vineyard],” said Sanford. He’d also later meet Thekla in a sailboat.

Before both the wine and the wife, Sanford and Wilson started a company that produced educational videotapes, but Sanford was not fond of the Hollywood types that they had to deal with. “It wasn’t resonating with me,” he explained. “I wanted to be outside, to be more earthly connected.”

Pioneering Pinot Noir

Sanford did not grow up with wine on the dinner table. But while in the navy, an officer named, no joke, Scott Wine introduced Sanford to a bottle of Volnay, a French pinot noir from Burgundy. “I still remember that Volnay,” said Sanford. “That became my threshold.”

So Sanford studied a century of weather reports from Burgundy, cross-referenced with California to locate similarities, and began driving around his 1950 Mercedes with a thermometer sticking out of the windshield. The process, said Sanford, “all seemed very obvious to me,” but he turned heads by suggesting that hills between Buellton and Lompoc might be perfect for pinot. That was due to the “very unique” climate fostered by the west-to-east lying Transverse Range, where, thanks to the ocean’s influence, the average temperature rises about one degree for each mile you drive inland. “I was interested in the variety of climates in the short distance,” said Sanford, whose list of possible pinot zones also included Los Alamos and Edna Valley. “That’s why the flower seed companies came here, too.”

But even with science on his side — not to mention nicely draining soils and landowners ready to sell — most thought cool-climate–loving pinot couldn’t be grown this far south. “The only thing that anyone went to Buellton for was the split pea soup,” remembered Wine Spectator’s Laube, who said the region was better known for surfing, row crops, and horse ranches. “People thought he didn’t know what he was doing.” And even though Sanford was confident, it was still a big leap. “When you go out and plant a vineyard like he did, there’s huge risk, and the outcome is uncertain,” said Laube. “There’s just no way to gauge how the project is going to go.”

Sanford teamed up with botanist Michael Benedict, and they started looking for investors at places like the Los Angeles Country Club. Thanks to an IRS loophole that benefited citrus, cattle feed, and grape-growing companies, Sanford explained, “I was able to offer them a very good loss on their investment.” With cash in hand and Sanford pledging sweat equity, the partners bought an abandoned 473-acre slice of Rancho Santa Rosa that had once been dry-farmed for beans and barley. In 1971, the 120-acre Sanford & Benedict Vineyard along Santa Rosa Road was planted with cuttings of pinot noir, chardonnay, riesling, merlot, and cabernet sauvignon that they’d started propagating the year before.

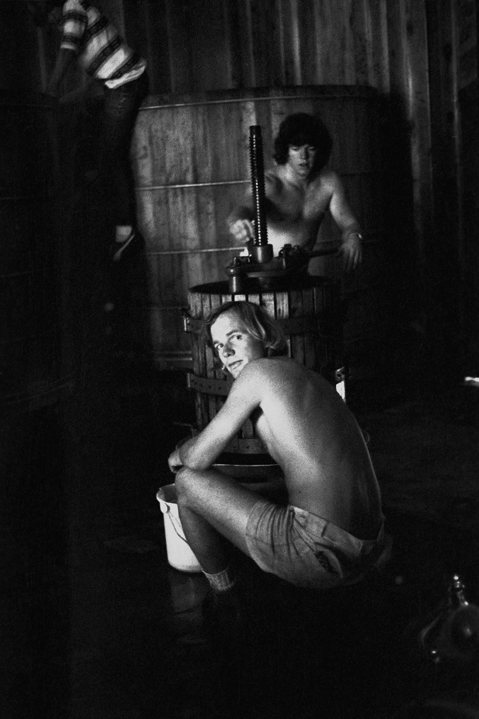

Sanford moved onto the property and became a tractor-driving farmer overnight, explaining, “You really learn fast. You have no choice.” With the help of Santa Barbara’s hot-tub pioneer Gary Gordon, they built open-top fermenters out of white oak that were eight feet wide and five feet deep, converted the old barn into a working winery, and awaited the first harvest.

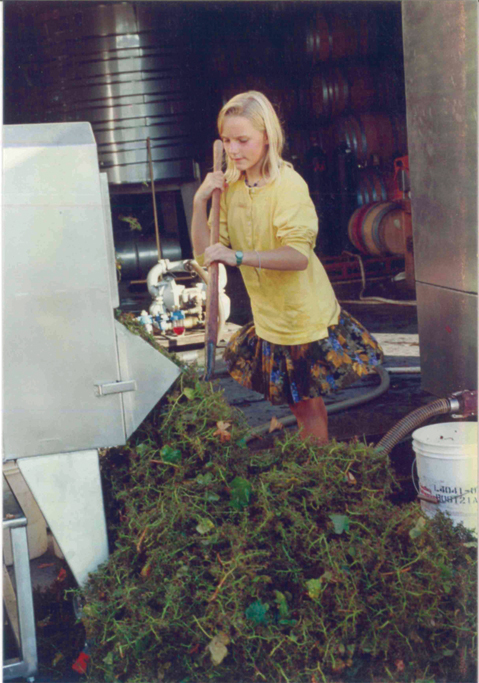

About that time, Richard and Thekla met on a Wet Wednesday in the Santa Barbara Harbor. She’d grown up in Wisconsin, where her family was connected to the Schlitz brewing empire, but came west by way of college in Tucson, Arizona, and a few years in Boulder, Colorado. Thekla distinctly remembers her first drive up to the vineyard. “I loved the fact that it didn’t have electricity,” said Thekla, who eventually married Richard there in 1978. “There was romance — a romantic feeling for Richard, yes, but that was all connected with everything else, too: the land, the vineyard, and also the families that were involved with us.”

She arrived in time for the inaugural 1976 vintage, and the pinot got quick applause, including an article titled “American Grand Cru in a Lompoc Barn” written by influential journalist Robert Lawrence Balzer.

Veteran wine seller Gary Fishman, of Wally’s Wine & Spirits in Westwood, said that the wine “caused a stir,” explaining, “I can’t say that it was wildly popular — at that time, pinot noir wasn’t on the radar that much — but for people who appreciated fine wines and knew Burgundy, they knew that he may be onto something.”

David Breitstein, who’s owned the Duke of Bourbon wine store in Canoga Park since 1967, included that pinot in his collection of the most important bottles ever produced in the state. “The Sanford & Benedict ’76 was one of the most historical wines in California,” he said. “Look at what went forward.”

But by 1980, the partnership fell apart. After meeting with each investor — they all sided with Benedict at the time — Sanford walked away from the vineyard. “It was hard to make wine by committee,” Sanford has repeatedly explained of the failed partnership. Benedict has never really offered his side of the story and, when contacted for this article, did not feel he could add “anything constructive.”

Leaving was crushing for the Sanfords. They had a young daughter and no idea of what was next. “That was a pretty magical place to be living for eight years,” said Sanford, but he relied on the Taoist philosophy of nonattachment to help, as he has throughout his life. “You invest a lot of your soul in an activity like this.” Thekla agrees. “It was really difficult to say good-bye to that place,” she explained. “But I believe in destiny, and if it’s supposed to happen, it will, and if it’s not, you have to walk away and let it all go.” Her intuition would be rewarded a decade later when the Sanfords eventually regained the Sanford & Benedict Vineyard in 1990.

Go Organic, Help People, Save Oaks

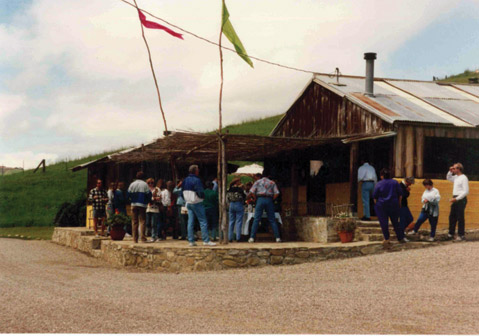

Just a year after walking away from their first vineyard, Richard and Thekla founded Sanford Winery in 1981, buying grapes from other vineyards at first. In 1983, they turned a Buellton warehouse into a winery and hired Bruno D’Alfonso as a full-time winemaker, a job he kept for a quarter-century. Sanford came into his own as the vintner, which is the face of the business. “He’s the consummate frontman, a lot of class, a very magnanimous human being,” said D’Alfonso of his longtime boss. “He hires really well, and he knows how to stay away. The majority of people he hired were good people and stayed with him quite awhile.”

The Sanfords also planted a new vineyard on their home property, Rancho El Jabalí, which Thekla — whose Wisconsin childhood included pesticide-free gardens, free-range chickens, and even the fast fad “beefalo” — insisted be done organically. They were one of the first farmers in the region to go organic. “I can’t think of anybody that was doing it,” said Thekla.

The pesticide-free pledge wasn’t just for nature, though. It was also to protect the health of the Mexican laborers who toiled in the vineyards day in and day out. “They are all part of our family,” said Sanford, who’s helped many get legal residency in the United States, proudly watched them buy homes and send their kids to college, and attended all of the resulting weddings and quinceañeras. The feeling is mutual. “He’s like family — I’m happy that I worked with him all these years,” said Martin Hernandez, who started working for the Sanfords at age 17 in 1975. And even the seasonal laborers recognize the Sanfords’ kindness, as Hernandez explained that some won’t work for other ranches. “Sometimes people don’t want to go because those ranches are different,” said Hernandez. “When they hear Alma Rosa, everyone wants to come work over here.”

In 1990, the Sanfords (as silent partners with British investor Robert Atkin) took back the Sanford & Benedict Vineyard and planted La Rinconada Vineyard in 1995 and La Encantada Vineyard in 2000. By then, they were farming nearly 450 acres of organic vineyards — complete with peregrine-falcon release platforms and bluebird recovery boxes — and approaching 50,000 cases of wine a year, making Sanford Winery one of the biggest producers in Santa Barbara County. Though they’d get certified as Santa Barbara County’s first organic vineyards in 2000, recognition was never the point, said Thekla, explaining, “It comes from so deeply inside of us.”

But the Sanfords did take a public stand in 1997 when 800 valley oaks were bulldozed by Kendall-Jackson to make way for a massive vineyard near Los Alamos. Said Sanford, “Uprooting nature is not being in harmony with it.”

The backlash from other farmers was vicious. “There were some serious sour grapes about a successful, charismatic, very popular, super-premium wine producer like Richard really taking issue with the way someone else was doing it,” said conservationist Greg Helms, who was working for the Environmental Defense Center at the time.

So when the Sanfords applied for permits to build their sustainable dream winery in the middle of La Rinconada Vineyard, the property-rights folks took revenge by calling him a hypocrite. “They didn’t want people out there saying, ‘Hey, we can have a fantastic product and make a good living with minimal environmental impacts,’” explained Helms. “That wasn’t something they could tolerate, so they were willing to engage in a very personal, difficult campaign against Richard and Thekla.” What did Sanford do? “He took it in stride,” said Helms.

That winery project, however, would prove disastrous in other ways.

Losing Your Name

One sunny afternoon last month, Sanford sat in his car on the side of Santa Rosa Road, beset on all sides by vineyards he either planted (Sanford & Benedict, La Rinconada) or inspired (Fiddlestix, Sea Smoke, Mt. Carmel). He stared out at the palatial Sanford Winery that he’d designed in the late 1990s and finished building in 2001, and he described the eco-extravagance of what some say is the largest adobe construction in California since the mission period: load-bearing, earthquake-safe adobe bricks made by hand on site, old-growth redwood recycled from a sawmill he bought in Washington, gravity-powered tank elevators. “Anyway,” summed up Sanford wistfully, “this was the winery of my dreams. It was a labor of love.”

It was also wildly expensive, with the initial estimate of $4 million or so exploding closer to $10 million when the last tile was laid in 2001. “Unfortunately, the winery cost too much,” admitted Thekla. “That got us into trouble.” Then came the 9/11 attacks, which killed wine sales for about a year, plus some weak harvests and more slow sales.

Eventually, the bank came calling, and in 2002, the Sanfords entered into a marketing deal with the Chicago-based Paterno Wines International (since renamed Terlato Wines International), which infused the struggling winery with a capital investment. Beyond that, the Sanfords can’t really discuss how business with the Terlato family unfolded, because they signed a non-disparagement agreement when everything fell apart in 2005. At the time, the Sanfords claimed it was because the Terlatos wanted to stop organic farming, and the Terlatos claimed that the quality of wine had plummeted. Today, both parties would rather focus on the future rather than the past.

But winemaker D’Alfonso, who was eventually fired by the Terlatos, was able to break down the breakup over glasses of Sanford & Benedict–grown pinot grigio one recent afternoon. Though the Terlatos’ initial investment was designed as a show of good faith, sales didn’t pick up, so through a number of capital calls, they were quickly able to gain a majority share in the company. “It was simply Business 101,” said D’Alfonso. And with the Terlatos in charge, the Sanfords came to a crossroads. “It was painful to watch this wonderful ride coming to an end,” said D’Alfonso. “Rather than mortgage his ethics for the new arrangement, he moved on to the Alma Rosa project with his ethics intact.”

Sanford cannot comment on this particular deal, but when asked if he regretted not being more cynical, he didn’t mince words. “I’ve always performed in a responsible way, and frankly, I have not been a cynic,” said Sanford. “When people don’t perform as to their word, it surprises me.”

Of course, in an industry where lofty dreams often crash into economic realities, Sanford is hardly the first vintner to lose his shorts. “It’s semi-ubiquitous in the industry,” said Fishman, the West L.A. retailer. “Wine is an aesthetic and an art, but like many great artists, you don’t realize your fortune until after you’re dead. It’s hard to combine business acumen with winemaking expertise. Richard unfortunately didn’t have the right financial coaching.”

Rebirth of Soul

The loss of Sanford Winery, in the words of daughter Blakeney, was “severely devastating” for the family. “We chose to leave,” said Thekla, “but we left with nothing, including our name.” Plus, adding salt to the wound, Sanford Winery’s tasting room remained on the family’s home ranch for a year-and-a-half, and the family saw it daily. “It was really not comfortable there,” said Sanford. “We had to be patient.”

Richard and Thekla took some time to think about their next move, even contemplating a departure from the wine industry altogether; one day while watching the windjammers cut through Maine’s Penobscot Bay, they pondered whether Sanford should go back to the sea as a boat captain. “But the reality is we like what we do,” said Thekla. “We love being in the wine business.”

So they came home, and, said Thekla, “put our energy into re-creating ourselves again.” They found a sunny, south-facing warehouse in Buellton — not unlike the first incarnation of Sanford Winery — and set up a tent camp inside, where longtime tasting-room manager Chris Burroughs held court once again. “It was fun. It was exciting. It was challenging,” said Thekla. “We did all sorts of creative financing, like credit cards.”

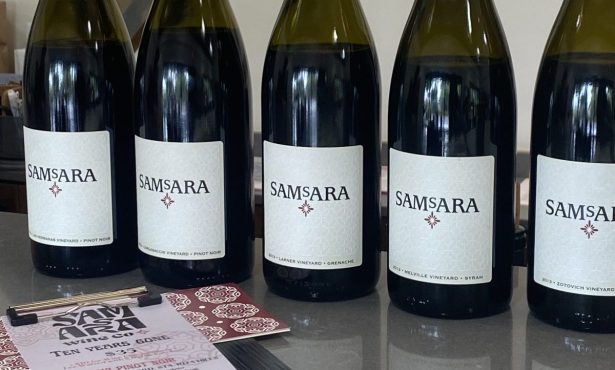

Because Sanford felt that the wines from the El Jabalí and La Encantada vineyards “reflected the soul of Rancho Santa Rosa” — the old land grant that contains those properties — they chose the name Alma Rosa (“alma” being “soul” in Spanish) and also tried to keep prices down in order to “have wines more generally available to a wider audience.” Today, they produce about 15,000 cases a year, both from those two vineyards as well as from fruit purchased elsewhere in Santa Barbara County, but still are actively working to improve their offerings. “Alma Rosa hasn’t reached its potential,” said Thekla last week. “It needs some care and resuscitation.”

Sanford, meanwhile, remains the frontman, attending festivals, presiding over dinners, and selling his wine face-to-face like he did in the 1970s. “It’s become more and more important to be out repping the product,” he explained. “There’s a lot more competition.” That’s only likely to increase, as the Sta. Rita Hills still has room to grow. “There is more demand for grapes,” explained Sanford, “but no new vineyards.”

Workload aside, Richard and Thekla have graciously accepted the praise that continues to be heaped on them. “I’ve just been out here doing this for 41 years,” said Sanford. “But I have been a pioneer. I finally decided to recognize that fact and enjoy that.”

Despite the ups and downs of his remarkable career, Sanford doesn’t regret a thing. “I don’t think that I would have done anything differently,” he said. “It’s been a series of experiments. That’s all we can do, right? That’s life, isn’t it?”

4•1•1

Richard Sanford and Alma Rosa are participating in the Santa Barbara County Vintners’ Festival on Saturday, April 21, 1-4 p.m., at The Carranza in Los Olivos (see sbcountywines.com), while hosting a “Day in the Country” at their tasting room (7250 Santa Rosa Rd., outside of Buellton) on both weekend days. Sanford will be honored on Friday, April 27, 5:30-9 p.m., as part of the UCSB Alumni Association Awards Banquet at Corwin Pavilion (see www.ucsbalum.com/agr) and again by the Environmental Defense Center on May 8, 6-8:30 p.m., at Avant Tapas & Wine in Buellton (see edcnet.org or call 963-1622 x103). For more on Alma Rosa Winery, see almarosawinery.com.