Stoker Enters State Assembly Race

Calls for Shrinking Government and Cutting Business Taxes

Preaching the Republican gospel of smaller government and lower taxes, Mike Stoker officially threw his hat into the ring for the 35th California Assembly District race. The Greka Oil Company spokesperson and former Santa Barbara County supervisor is the only Republican candidate to emerge so far and is his party’s probable nominee.

Stoker’s Democratic opponent is likely to be either Santa Barbara City Councilmember Das Williams or environmental activist Susan Jordan, wife of Pedro Nava, who is termed out as 35th District assemblyman. The district stretches through parts of both Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

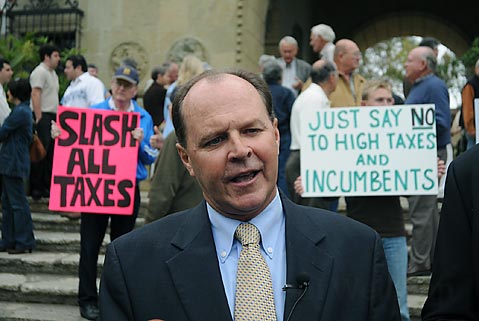

At the County Courthouse on Friday, May 29, with about a hundred supporters arrayed behind him like a choir on the Sunken Garden steps, Stoker stepped up to the podium and sketched out his positions for the coming campaign.

Emphasizing job creation and retention, Stoker inveighed against “job-killing legislation that does very little or nothing to protect the environment but puts California businesses out of business” or causes them to leave the state. He called for spending caps, which would stay in place when the economy recovers. Had government grown only at the rate of population increase and inflation over the past decade, he claimed, California would now have a “$15- to-$20-billion surplus versus a $45- to-$50-billion deficit.”

Stoker drew cheers from the crowd by characterizing government as issuing “blank checks” to public employee unions. He called for reducing the number of government employees with the exception of police, firefighters, and others who risk their own lives to save others’. “They should be exempt,” he said. Answering reporters’ questions afterward, Stoker claimed that government services would not be compromised by cutting workers. He could cut 20 percent of social workers he said, “and have the remaining 80 percent pick up their caseloads, and it’s a good thing.” When the economy was growing, the state hired more workers than it needed, Stoker said. The state should balance its budget by cutting the number of state employees, he emphasized.

As a real-life example of such efficiency, Stoker cited his leadership on the Board of Supervisors (BOS), where he served from 1986 to 1994. The BOS halved the Air Pollution Control District’s (APCD) workforce, he said, from 260 people to 120, reducing the budget from $14 million to $6 million-and a year later Santa Barbara County met federal air quality standards for the first time.

The APCD’s current executive officer, Terry Dressler, disagreed with Stoker’s recollection. At its height, in 1993, to deal with eight new offshore platforms and three new onshore oil-and-gas processing facilities that were being constructed, the APCD’s ranks swelled to 113 workers, Dressler said, with fees to the oil companies helping foot the bill for the extra work. When Stoker left office a year later, staff was down to 93 workers and the budget was $11 million. The county first attained the federal ozone standard in 1999, Dressler said. The decreased workforce was largely due to a decreased workload with the completion of construction, according to Dressler. Stoker conceded as to the precise numbers, but noted the controversy at the time over eliminating so many APCD workers.

According to County Auditor Bob Geis, the APCD workforce continued to diminish incrementally and now stands at 50 workers with a budget of about $11 million, the same as when Stoker left office in gross dollars but “significantly less” when inflation is taken into account. Geis added that Stoker “led a significant effort . . . during the recession of the ’90s to reorganize county government.” He added, “I think everyone can be proud of the levels of efficiency and effectiveness the APCD has achieved.”

Asked about his role as a spokesperson and consultant for Greka in the wake of its numerous onshore oil spills in the past few years, Stoker said he was brought on board, along with a new company president, to help turn the company around once the owner “decided he wanted to be a good corporate citizen.” Stoker praised the newfound aggressiveness county regulators displayed following the two spills, a year and a half ago, which escaped containment zones. Upon his recommendations, Stoker said, the owners responded by spending $36 million to add secondary containment berms and address longstanding equipment problems, and by implementing round-the-clock monitoring by live operators at each Greka site in the county. The company is now into the second year of a five-year Greka Green program designed by himself and the new president, which Stoker said should make Greka “a role model for onshore oil and gas companies.”

Besides cutting public employee unions, the other area Stoker marked for reduction was school administration, which he said was only 2 to 3 percent of the education budget in the 1960s, when California’s educational system was rated first in the nation.

Stoker and State Senator Tony Strickland, who joined Stoker at the podium and promised to walk as many precincts for him as he had for himself, repeatedly hearkened back to the California of the 1960s, when California led the nation not only in education but in job creation. Stoker invoked the name of former Governor Pat Brown, a Democrat, who presided over the building of much California infrastructure, including the freeways. Stoker said he worked well with what he called Chamber of Commerce Democrats. “I tell them if I was as liberal as you are, with all the programs you want to create, I would be more pro-business than Mike Stoker.”