Shine a Light

Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, et al. star in a film directed by Martin Scorsese.

Creating a modern day-aka retirement age era-Rolling Stones concert film may have been a necessary and risky job, but somebody had to do it. And thankfully that someone was longtime fan Martin Scorsese. Scorsese has used many a Stones song in his film soundtracks dating back to the ’70s, long before pop songs in movies became a tired cliche. Here, Scorsese returns the favor, creating a vibrant concert movie that does its basic job, capturing the band’s particular electricity, and sneaks in some cinematic seduction and trickery.

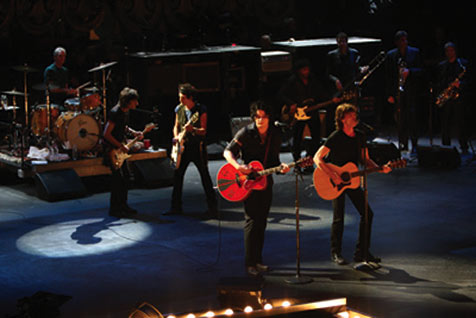

Shot at N.Y.C.’s Beacon Theater, Shine a Light gets in the face of the inimitable Stones vibe, bearing witness to a band that has managed to turn arrested development into a career-and have infectious fun doing it. Guests include Jack White and Christine Aguilera, but they’re unnecessary younger-generation props for a classic songbook that runs from the mid ’60s to today.

Oddly enough, the dualistic characters in the protracted “plot” of the Stones saga lay in the famed Jagger/Richards teaming. In concert and in life, we keep expecting Richards-the woozy slacker compared to Jagger’s neurotically kinetic livewire-to be the one who falls down. In the film, Richards is all about cool, melting angles and signature behind-the-beat guitar playing. He drapes himself on band members and drops to his knees to play before the hearth of Charlie Watts’ kick drum. In one sneaky cutaway shot, we watch Richards spit his cigarette butt out onstage. Later, he makes a gift of his Gibson 335 guitar to guest Buddy Guy. Meanwhile, Jagger’s athletic restlessness is still the Stones’ focal point. He runs, dances, wriggles, and otherwise can’t stand still, even at 60-odd years old.

Among the film’s charms is its respect for the Stones’ musical integrity. Scorsese refuses to edit songs down, and the approach works because the Stones are such masters of the extended, ecstatic ending vamp, of which we get many here.

The concert film genre is fairly oxymoronic and absurd, like the proverbial eunuch at an orgy. But when the films are good-like this and like Jonathan Demme’s Neil Young film, Heart of Gold-they can be valuable documents and can imitate the buzz of the “real” thing for fleeting moments, before you snap awake and realize you’re just watching lights flickering on the screen and that the performers won’t hear your applause.