Children Go Hungry in Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara County Has the Highest Child Poverty Rate in California

California has the fifth-largest economy in the world, with the highest rate of child poverty in the United States. The largest percentage of hungry California children lives right here in Santa Barbara County — more than 28,000 children are at risk of not having enough to eat. This number has been rising steadily for almost a decade, and organizations from federal food services to public school cafeterias are trying to help.

McKinley Elementary School, for example, has a vibrant and vital program. Every midday, the cafeteria bustles as kids line up to receive their school lunch. More than 90 percent of these children are from families living on or below the poverty line, and this cafeteria often provides the only free and wholesome meals they might receive all day. The kids are excited with their choices today — an incredible array of options including pozole, chicken and veggie enchiladas, and a colorful, inviting salad bar. It even has veggies covered with Tajín, a popular Mexican seasoning made of ground chili pepper, salt, and dehydrated lime.

McKinley Elementary is part of the Santa Barbara Unified School District (SBUSD), which has one of the largest ongoing projects combating child hunger in the county. Within the district, approximately 7,400 of its 14,500 students qualify for the National School Lunch Program, which provides children of low-income families with meals at school each day. To have qualified for reduced-cost meals for the 2017-18 school year, the federal government required that a family of four make no more than $45,510 a year; for free meals, the income ceiling was $31,980. However, in Santa Barbara, as in other wealthy sections of the country, housing costs are so high that poor families are forced to live in extremely overcrowded and often unreliable housing. More than 2,000 children in the Santa Barbara school district live in tight quarters or must move from location to location as rents rise. These conditions are generally classified as homeless, and in our ever-tightening rental market, this phenomenon is not uncommon.

Gina Cuevas, who coordinates the Federal Food Service Program in the SBUSD, believes that the number of homeless children is even higher than the 30 percent increase noted since 2017. That increase is only based on the application families must submit to qualify for free or reduced-cost meals. Many families, she said, register with an online form that has some confusing language, and of course, increasingly some families are afraid to even return the application at all since it asks for the primary wage earner’s Social Security number. Even though that number is not required, and a student’s citizenship status is not ever asked, the fear of deportation is so great that the question is enough to dissuade them from returning the form. Nancy Weiss, director of SBUSD Food Services, estimates an additional thousand kids within the district qualify for the program but have not submitted an application.

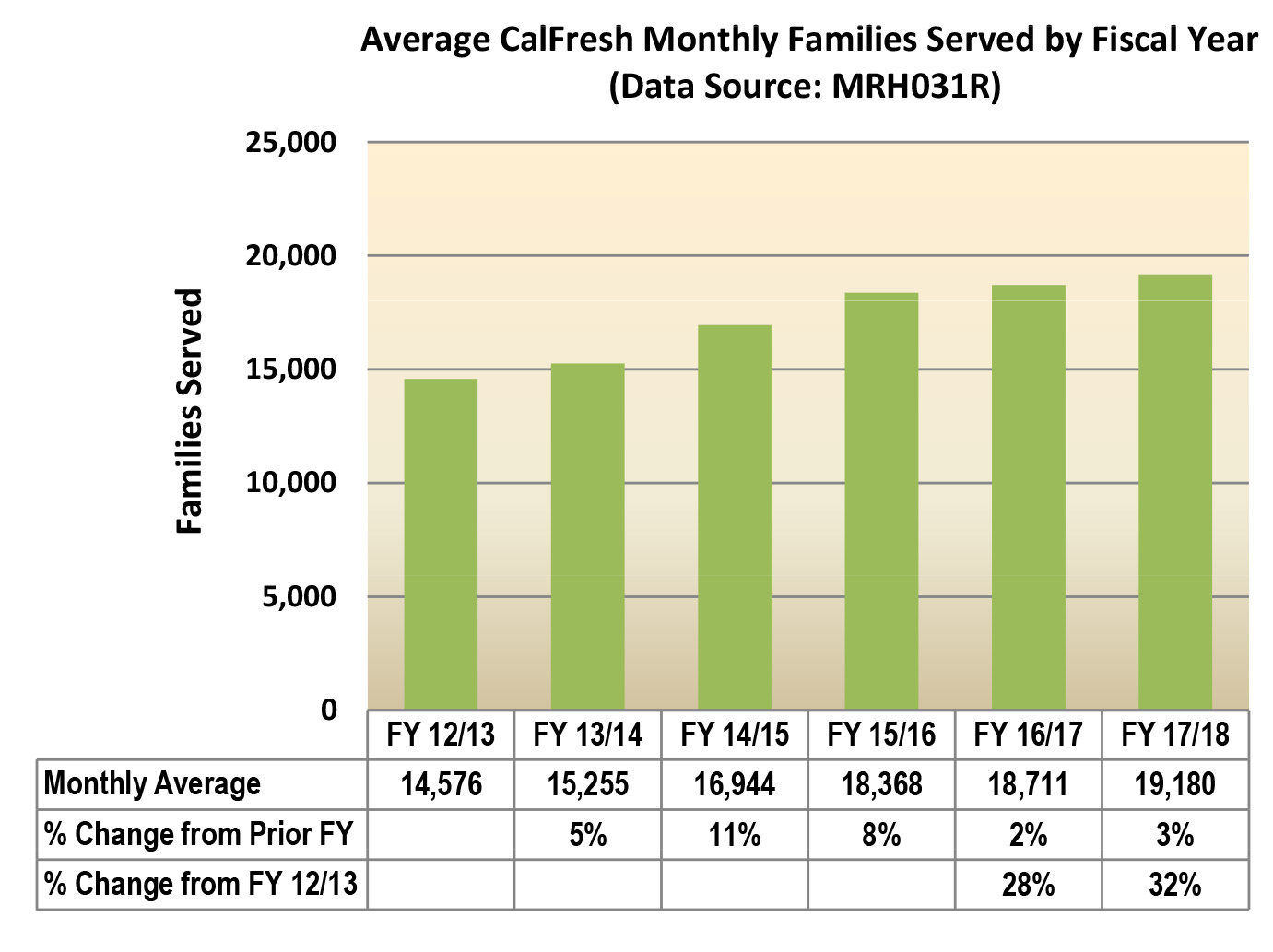

Our county has also seen a 32 percent increase over the last five years in families enrolling for food stamps, officially known as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) federally and as CalFresh in California. CalFresh serves an average of 19,000 families a month county-wide. To qualify, a family of four must make less than $49,200 annually, and only U.S. citizens or legal residents within the family can receive the benefits. All working-age adults must prove that they are employed a minimum of 30 hours a week. Families that fail to comply have benefits cut off, including those for children.

Skyrocketing rents are the cause of poverty in Santa Barbara County, not unemployment. Most children have at least one parent working full-time, and more often than not, both parents are working more than one full-time job. High rents are the direct cause of the increasing rate of child poverty. Families are forced to choose between having access to jobs and paying housing costs that exceed half of their income or moving to areas where employment is scarce.

This situation for many families in our county comes as no surprise to Michael Baker, chief executive officer of the United Boys & Girls Clubs of Santa Barbara County. “I was one of those kids,” said Baker, whose own family struggled with poverty as he was growing up. Baker recognized that the breakfast and lunch being provided at school were still leaving kids with nothing to eat on the weekends. “At the end of the month, families are out of money,” said Baker. So he talked to Dave Cash, who at the time was the SBUSD superintendent. Cash agreed to have the schools’ food services provide brown-bag lunches on Saturdays at the Westside Boys & Girls Club. Cash also connected Baker with Weiss. She offered to organize a supper program on the Westside, where 98 percent of students live on or below the poverty line. Through federal government funding, Weiss was able to send a food truck to the club Monday-Friday, providing free supper to every person age 18 or younger. Adults could pay $4 and join the kids. Baker estimates they serve 150-200 dinners a day. Toward the end of the month, he said, he sees parents splitting one meal in two.

Since the first supper program in 2015, Weiss has expanded to 13 other locations, providing an average of 1,200 meals nightly from Santa Barbara to Isla Vista. All year long, the SBUSD continues its free food services; in the summers, they have been serving more than 3,000 kids. In June, the mobile cafés will expand into Carpinteria and Buellton, two very-high-need areas. Carpinteria currently has 64 percent of its students qualifying for free and reduced lunches.

Children living in poverty have a higher likelihood of being malnourished and in poor health. Weiss’s mobile cafés and food services directly combat those statistics. Weiss’s insistence on using fresh, local, nutritionally rich food provides students with a balanced diet and the necessary nutrition for a strong immune system, making them less likely to need medical care. Weiss jokes, “If students eat with me from K-12, it’s like they’re being put through a natural immunization program.”

The food being served to our students is very unique to Santa Barbara, she said. Weiss partners with local farmers and small businesses to provide fresh, seasonal fruits and veggies. All the food is made from scratch, including sandwich rolls, granola, and salad dressings, avoiding high-fructose ingredients, hormones, hydrogenated oils, and other additives. And, in partnership with Hungry Planet, they even provide vegan options.

Weiss makes it a point to include culturally familiar foods such as pozole, quesadillas de rajas, tacos de adobada, and tostadas; “It gets them excited,” she said. Students are also exposed to vegetables they’ve never tried before and experience healthy, fresh food. Weiss has a motto she tells the kids: “Eat to live, live to learn, and learn to eat.” Weiss and her service to the community are making that possible.