Public Safety in Goleta

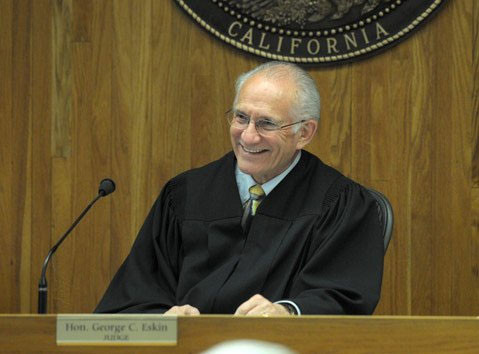

A Talk with Retired Judge George Eskin

High on the list of what Goleta residents expect from city government is public safety. We want to feel safe from threats such as theft, damage, and violence. Concurrently we don’t want to live behind barricades or spend the entire city budget to ensure our safety.

Our first line of defense is having Goleta’s own police department. Under Goleta’s contract with Santa Barbara County, the Sheriff dedicates officers and detectives to patrol and solve crimes in Goleta. However, it’s well worth noting that the $8.2 million cost of these services consumes nearly 40 percent of Goleta’s $22.9 million operating budget.

Goleta crime rates are relatively low compared with other California cities, thanks in no small part to our Sheriff’s Office (and our county’s criminal justice system, including probation, prosecution, public defender, and related departments.) But the cost of policing services is projected to rise faster than Goleta revenues, essentially eroding funding so badly needed for services and infrastructure such as street repair, libraries, recreation, and a new City Hall.

To learn about opportunities to reduce both crime and the policing costs, we turn to an expert, retired Superior Court judge George Eskin, who has 50 years of experience in the criminal justice system as a prosecutor, public law office administrator, defense attorney, and judge. He was certified as a specialist in criminal law for 25 years and served on the Criminal Law Advisory Committee to the California Judicial Council.

Are there are any opportunities for reducing crimes and maintaining or even reducing societal costs? Or are we faced with mounting policing and jail costs just to stay at our current crime rate?

One opportunity for reducing the costs associated with law enforcement is replacing the “criminal” label we have attached to certain nonviolent conduct. In a recent veto message, Governor Brown observed that “California’s criminal code … cover[s] every almost conceivable form of human misbehavior” and “Before we keep going down this road, I think we should pause and reflect how our system of criminal justice could be made more human, more just, and more cost-effective.”

Sure, some states have decriminalized some behaviors, such as the growing movement to make personal possession and use of cannabis legal. But are there other options to reducing policing and incarceration costs for criminal behaviors we want to discourage?

Yes. In our county recidivism rates by people whose behavior is impaired by mental illness and drug addiction is over 50 percent. Indeed, recognizing the enormous cost of mass incarceration in the United States and the failure to reduce recidivism, there has been a bipartisan effort in Congress, supported by President Obama, to change our approach to crime and punishment.

Mental illness and drug addiction should be treated in appropriate mental health and public health facilities; those charged with nonviolent offenses who need mental health and addiction treatment should not be going to jail. Much like our history with the failure of Prohibition, the so-called “War on (Other) Drugs” has not only proved to be an abject failure but also a financial disaster that has created massive societal problems. Drugs are more easily available and in greater demand, plus drug cartels have flourished, much as did organized crime syndicates during Prohibition.

Are there other places that have tried more successful approaches that we can learn from?

I recently returned from a trip to Scandinavia, where I was able to meet with criminal justice authorities in Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Oslo. Their approach to crime and punishment presents a stark contrast to ours, and their recidivism rates are far lower. Following an arrest, law enforcement agencies first determine whether a defendant’s pretrial incarceration is required for public safety. Release from custody with therapeutic conditions and use of an electronic monitoring device is customary, resulting in lower jailing costs and better treatment options.

Prosecutors and judges there seek noncustodial sanctions following conviction, the length of prison sentences is much less than ours, and the primary concern of custodial officials is the prisoners’ “reentry” to society. Release from custody occurs when it is determined that a prisoner is “ready” for release and not by a predetermined, fixed sentence imposed by a California trial judge who rarely receives input from prison officials at the time of sentencing.

What kind of “reentry” preparation is available in Scandinavia?

Inmates receive education, job training, and treatment from an assigned team. Of course, there are some incorrigible offenders who commit crimes of violence, and they are easily identified and not released from custody. It is essential for me to emphasize that the reforms I advocate do not extend to crimes of physical and financial violence.

What about Prop. 47? Won’t this result in even more criminals being let out on the street to offend again?

Prop. 47 has led to a 40 percent reduction in felony case filings, and that should produce significant savings for the courts if vigorous case management policies and practices are adopted. Although crimes of violence are the focus of media attention, the vast majority of cases that occupy the courts are misdemeanors with the potential of incarceration for less than one year. The financial savings realized by Prop. 47 will be available for education, treatment, and housing programs starting in 2016, and local agencies should be preparing grant applications for submission when the authorizing legislation, Assembly Bill 1286 (“The Second Chance Fund”) is signed by the governor.

Do we need a new jail, and how will that help? If not, what’s the alternative?

I continue to believe that we need a North County detention facility with easier access to the courts, especially for people whose cases have not yet been adjudicated. However, I question the required size and capacity. A better alternative to massive jail expansion is reducing the jail population by referring those with mental illness and drug addiction to public and mental health facilities, improving the reentry process, and reducing the 50-plus percent recidivism rate; and, we need to expand non-custodial sanctions through our excellent Probation Department.

What can/should the public do in terms of urging city and county leaders?

We should begin by insisting on a departure from the failed policies of the status quo and instead provide resources for education, job training, and treatment by qualified professionals. We should advocate for recognizing that those suffering from mental illness and addiction should be treated. We must question whether incarceration is appropriate for nonviolent offenses and increase focus on the inevitable reentry to society of those who have been incarcerated.

We have more people in prisons and jails in the United States than every other country on earth combined, and reentry programs and diversion from custody should be expanded. If we do not acknowledge that a policy of lengthy mass incarceration has proved to be a failure, public safety-related costs will continue to rise, and public safety will continue to be threatened.