Water Polo Veteran

Kenny Constantinides is the guy nobody wants to meet in the deep end of the pool — or, for that matter, anywhere in the water. A ferocious defender with an awesome outside shot, Constantinides has been blessed with a radar that renders the violent chaos of water polo magically coherent. In 2006, he churned the water for Santa Barbara’s 18-and-under club that won the national Junior Olympics in Southern California. That same year, he played for the Santa Barbara High School team that won the CIF Division II water polo championships. Had Constantinides taken the obvious path, he would have been showered with scholarship offers from Division I schools, entranced by his game-changing abilities. He’d have been a star.

But that would have been too obvious.

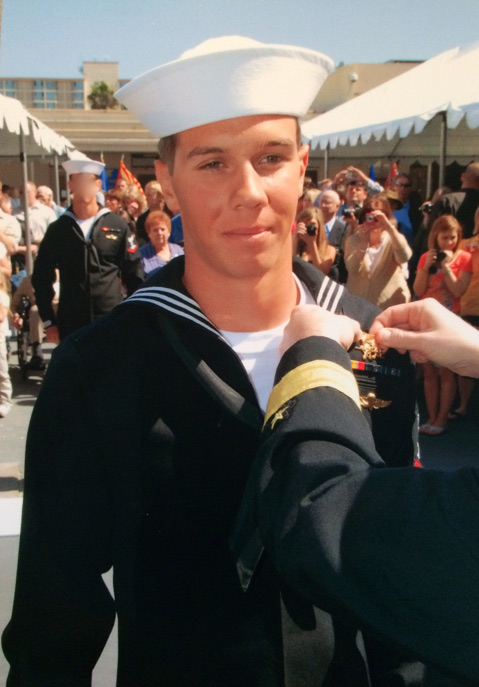

And Constantinides, it turns out, had other ideas. By the time he was 17, Constantinides was determined to become a Navy SEAL, one of the most elite fighting forces in the nation. Despite protests from his parents, coaches, and friends — there were, after all, two wars going on — Constantinides proved resolute and utterly intractable. At age 18, he signed up. Three days after turning 19, he started Hell Week, the most insanely grueling period of the most insanely grueling training camp of any in the armed services. Of the 280 enlistees to start down this excruciating road, only 33 made it. He was one. After six years — two dedicated to training and four with deployments in Iraq and Gulf States — Constantinides decided it was time to go home; to Santa Barbara.

That was June 2013. Today, Constantinides is at UCSB, one of nearly 500 veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars enrolled there. He’s signed up for four classes — 14 credits — a full load. This week, at age 25, he took his first midterm exam. Constantinides also works 24 hours a week as an emergency response technician in Isla Vista for the Santa Barbara County Fire Department. His ultimate dream is to work for a fire department in Santa Barbara County. To that end, he also attended — and aced — Allan Hancock’s fire academy last year.

And then there’s water polo. That’s another 25 hours a week. “I’ve never not been busy,” Constantinides explained. But it’s more than that. “First, I missed the game,” he said. “Second, I wanted to see if I still had it. And third, I missed the game.”

After an eight-year hiatus, Constantinides is back in the pool but this time among much younger players — not an easy task. But despite that handicap, Constantinides is managing to play for one of the top 10 water polo teams in the country, led by its legendary coach, three-time Olympian Wolf Wigo. Constantinides is not a starter, of course. That would be too much of a Cinderella story.

As he readily admits, he has never been a fast swimmer, and he’s playing for a coach who is famously all about speed. Instead, Constantinides has been assigned the function of “a role player.” That means he’s a defensive beast who drapes himself aggressively over the opposing team’s chief scorers. It’s his function to wear them out. It’s also his function, as Coach Wigo explained, to do the same to his top offensive players. Kenny brings “a mature intensity” to the UCSB team, Wigo said, and he gets along well with the younger players. But in practice, he force-feeds them a daily dose of physical, in-your-face defense that Wigo hopes will stand them in good stead during real games.

In person, Constantinides is low-key and reserved, exuding a sense of unshakable calm, leavened by flashes of shy, sly humor. It’s hard to tell whether Constantinides is more the irresistible force or the immovable object. Listening to friends and family, he might well be both.

Born to Be Wild

Born in Santa Barbara, Constantinides spent his grade school years in Vandenberg Village outside of Lompoc, where his mom, Julie Constantinides, ran a preschool operation and then a coffee shop. More recently, she obtained a nursing degree and for the past eight years has worked for Cottage Hospital in the postpartum unit. His father, Christo, is a legendary tugboat captain for the Castagnola family, known for his cool head and preternatural durability. Christo grew up in Khartoum, Sudan, living in a Greek settlement there, speaking Greek and Arabic. When Sudan declared its independence from the imperial cabal of English and Egyptian interests ruling that nation, the family moved to Santa Barbara, where Christo’s sister was then attending Westmont. That was 1961; Christo was 11. His parents wound up running a tuxedo rental and alteration business next to Mel’s, for decades one of Santa Barbara’s signature bars.

Julie was also 11 when she moved to Santa Barbara with her family from upstate New York in 1971. Her father was an engineer conducting sonar and acoustical research for the R&D firms sprouting up throughout Goleta Valley. A determined soul who knew her own mind, Julie — as she put it — was “out the door” by age 17. But by the time she was 25, she returned to Santa Barbara, where she met and married Christo.

In the Constantinides household, Julie would be the lightning, Christo the bottle. Together they’ve raised three sons: Nico, Kenny, and Alec. All the kids turned out to be athletic. The youngest, Alec, is now a fantastic golfer and works at a golf shop. But it was Nico, the oldest, who first got into water polo because a friend’s older brother played. Kenny would follow Nico’s lead. The two first played together at the club level in UCSB’s ancient pool, now more than 80 years old and leaking like a sieve, the subject of considerable derision in the water polo world.

It became immediately obvious that Nico was an accomplished player and that Kenny was something special. He was, his mother recalled, exceptionally competitive in any sport he took up. One year, Kenny kicked every goal scored by his soccer team. But Lompoc was not a convenient location for aquatically obsessed boys and a seafaring father. The nonstop shuttle to waves and water took its toll. After a family vote, the Constantinides moved from the comfort of their four-bedroom home in Vandenberg Village to the confined coziness of a two-bedroom home on the upper Westside.

Kenny enrolled at La Cumbre Junior High School, where everything about him immediately bugged Nick Mason, now one of his best friends. “He was tan, the front of his hair was always spiked up, and he always wore this tight choker of white puka [shell] beads,” Mason recalled. And his feet were huge, size 14. “We butted heads.”

Somehow the two managed to get over their mutual irritation and became fast friends. Nick lived on Mesa Lane right next to the Wilcox Property (a k a the Douglas Family Preserve), and Kenny’s backyard was Elings Park. It would have been impossible to conjure a more idyllic setting for those two growing up. They spent their time riding bikes, skateboarding, shooting airsoft guns, and surfing Hendry’s Beach. “Let’s just say we did not play video games,” Mason said.

The first school Kenny played for was San Marcos High, following his brother Nico. “For me, it was a lot of fun to be able to play with Kenny,” said Nico. They were the two players other schools would key on. Despite his youth, Kenny quickly emerged as the best player on the team. “I was never a great shooter,” Nico said, “but Kenny was a hell of a shooter, and he had a creativity and style that was singular. There was a spontaneity in how he played.”

And Kenny was extremely physical.

There’s No Place Like Home

Water polo is a ruthlessly tough contact sport, one frequently likened to rugby or boxing. One of Kenny’s coaches estimated fouls take place about every eight seconds. Because most of what happens occurs underwater, it’s impossible for referees to catch most of them. “Kenny makes a great effort to keep his hands up where the ref can see them the way you’re supposed to,” Nico recalled. “But he’s really good with his legs. So Kenny’s hands would be up in the air, but the guys he was guarding would be drowning.”

Kenny compared water polo to “nonstop wrestling,” saying, “I like the physicality of it, but it’s also a strategic game. It’s a thinking man’s game. Not like chess, where you can take a sip of coffee while you ponder your next move. You have to react quickly, under pressure, under cardiovascular stress.”

With water polo, the line dividing dirty play from physical is murkier than in most sports. For Kenny, dirty is punching, kneeing, and grabbing your opponents’ testicles. Everything else is pretty much okay. The way he played, however, dirty was unnecessary, gratuitous almost. As Nick Mason, who played with Kenny at Santa Barbara High School, said, “Nobody wanted to go one-on-one with Kenny. He was fearless in attacking the biggest player on the opposing side.” (Kenny transferred to Santa Barbara because that’s where all his friends played, but only after Nico graduated from San Marcos.)

Mark Walsh, his coach from Santa Barbara High, recalled watching Kenny go up against Hungarian players during a European club competition right before his senior season. The Hungarians were much bigger, stronger, and dirtier. “And they just wanted to beat the crap out of the Americans,” Walsh said. “We had one player who was giving it back. That was Kenny.”

Rich Griguoli, who coached Kenny’s club team, was struck just as much by Kenny’s absolute will to win as by his aggressive style. “When the game was on the line, he was the guy you wanted in the water,” he said. At the national Junior Olympics, Grigoli recalled, the game was tied with only seconds left. Kenny got the ball and flung one last shot at the goal. It sailed off the top beam, landing right in front of one of Kenny’s teammates. He shot it and scored. The game was won. “That’s not how Kenny planned it,” Griguoli said. “But it’s how he made it work.”

When Kenny announced he intended to join the SEALs right out of high school, nearly every adult in his immediate circle of coaches, mentors, and relatives freaked. They worried if Kenny didn’t make the SEALs — as most don’t — he’d be stuck in a dead-end assignment for the rest of his enlistment. Given Kenny’s skills, he could get into any number of prestigious schools. Why risk so much, they asked, when other paths were open?

His father, Christo, had come of age during the Vietnam War, which he decidedly did not support. Only by luck did he escape the draft. Aside from one of his mother’s uncles who had spent seven years in a North Vietnamese prisoner-of-war camp, there was no military tradition on either side of the family.

Nico, Kenny’s older brother, was then attending the University of Southern California’s film school, where he graduated at the top of his class, when he heard Kenny was applying for the SEALs. “It was a huge shock, surprise and confusion,” he said. “It popped up out of nowhere.”

Not so, said Nick Mason, who remembered Kenny devouring every book written on the SEALs at the time, even reading them during class. Even though all of Kenny’s friends knew his plans, they still found themselves stunned when the moment actually came. “We all graduated from high school,” Mason said, “and one week later — bam! — he was gone.”

In deference to his parents, Kenny had agreed, after much arm-twisting, to visit the Naval Academy during his senior year of high school. The water polo coach there was extremely interested in Kenny. The feeling was not reciprocated. Kenny worried that if he applied to the SEALs via the Naval Academy and didn’t make it, he’d have to wait — according to the rules and regulations — at least three years before trying again. If he applied directly out of high school and then flopped, he could try again the next year. Besides, when he visited the Naval Academy, he really didn’t like it. “It was too militaristic,” he said. “If I’m going to go to college, I want to go to a real college, a normal college.”

Just to make it into boot camp, Kenny took on a training regimen that even today makes his friends wince. Five days a week, 90 minutes a day, he put himself under the draconian tutelage of Victor Chakarian, who runs the Olympia Studios on Milpas Street and had been Kenny’s conditioning coach at San Marcos High School.

“Victor’s line was, ‘If I say the milk is black, the milk is black,” Kenny said, imitating Chakarian’s thick Russian accent. Chakarian — sufficiently old-school to still use medicine balls back before it became hip to do so — is light-years away from a stereotypical personal trainer. He had Kenny running from his gym to La Cumbre Plaza carrying a 35-pound kettle bell. Chakarian picked him up halfway. “‘I just wanted to see if you’d do it,’” he explained. Other training sessions were at the beach to simulate some of the cold-weather, wet-sand training for which the SEALS have become justifiably infamous. A woman passing by was so appalled by what she saw that she threatened to call the police. And at the same time, Kenny was also taking jiujitsu training. Five days a week. Ninety minutes a day.

All this, of course, paled compared to what he endured during the first five weeks of SEAL training. Given the investment involved — reportedly $1 million per year per SEAL — the Navy has staggered its program to encourage those not likely to make it to leave sooner rather than later. It’s called Hell Week for a reason. It doesn’t disappoint. New recruits are limited to a total of four hours of sleep over a six-day period. The rest is nonstop motion, activity, endurance, and work. When it was over, his mother recalled, Kenny’s body had grown so stiff and puffed up that he couldn’t even move. To make it, Kenny said, “You either have to be crazy, stupid, or a little bit of both.”

The SEALs reportedly take a dim view of body art. Kenny waited until he qualified before acquiring tattoos: The American flag and the Statue of Liberty runs the full length of his right thigh. Then there’s the image of Jesus wearing the crown of thorns on his left calf and a Spartan helmet on his right. “That’s pretty much my yin and yang,” he explained.

When it comes to talking about the SEALs, Kenny is extremely guarded. It’s not part of the code. When doing several ride-alongs with city firefighters, he asked his former coach Rich Griguoli — now a city firefighter — to keep mum about his SEAL experience. He wanted people to know him for who he was now and what he did, not what they imagined a SEAL to be. Griguoli refused to oblige. “It’s an amazing accomplishment,” he insisted. SEALs, for whatever reason, generate instant media buzz. Fox News is nonstop about its impending exclusive with the SEAL who shot Bin Laden. Kenny’s comment? “I didn’t shoot Bin Laden.”

Kenny said the attack of 9/11 stirred his interest in becoming a SEAL. As for the war itself, he said, “I believe the war was just,” but … the biggest blunder, he said, was excluding anyone affiliated with Saddam Hussein’s ruling Ba’ath Party from the new government.

While Kenny was discovering just how American foreign policy was taking shape on the ground, his brother Nico was having political epiphanies of his own. Nico, an accomplished filmmaker, immersed himself in the Occupy Wall Street movement, where he used his cinematic skills to give voice to the growing protest. Since then, his political views have shifted further to the left. That two brothers — who share the same birthday — could be so close and so far apart is a mystery. Nico and Kenny “get into it,” as Nico said, but there’s still affection, still respect. Kenny described their differences as “Nico’s more of an optimist; I’m more of a realist.”

What that means precisely is hard to say. Kenny is guarded about his own political worldview. Should he ever run for Santa Barbara City Council — as he’s indicated an interest in — Kenny will find himself pressed harder to define himself politically.

Nick Mason described Kenny as a “checklist” kind of guy. So, too, does Kenny. Had he signed up for another term with the SEALs, Kenny stood to reap a sizable financial bonus. He chose not to. “I did a lot of things I wanted to do,” he said. “A lot of boxes got checked.” He got to serve his country, see firsthand the situation in the Middle East, and be deployed alongside Iraqis. Now he’s in school studying political science with a minor in education. But the real reason Kenny didn’t sign up was simple. “Santa Barbara was the reason,” he said. “I got out because this place is my home. I want to be back here.”

In the meantime, Kenny Constantinides is in the pool playing a sport that he loves. He’s not getting as much time as he’d like. “It’s harder than I expected,” he said. But it’s another box on his check-off list of things to do: another challenge — improbable bordering on the impossible — confronted and met. And no, he said, there are no regrets about taking so much time away from the sport. “Water polo is a game. It’s fun,” he said. “But there is so much more going on.”