What Doctors Should Learn from Veterinarians

Zoobiquity's Kathryn Bowers on Anorexic Pigs, Ancient Erections, and Growing Up in Goleta

We take for granted that humans and other species on the planet share a great deal of physical traits — legs and eyes and brains, for instance — and we’re even happy to admit that some similarities go deeper, acknowledging that other critters might have personalities, that some even seem to use tools. But we’re very afraid to consider that we noble, exalted humans might actually have vastly more in common with these so-called beasts and that by studying animals, insects, and even plants we might learn a great deal about ourselves.

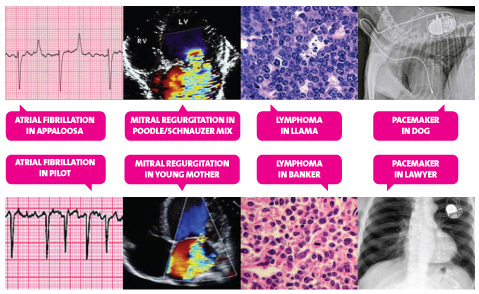

Such discoveries are at the heart of Zoobiquity: What Animals Can Teach Us About Health and the Science of Healing, a new book written by UCLA cardiologist/psychiatrist Barbara Natterson-Horowitz and journalist Kathryn Bowers that explores, among other fascinatingly convergent topics, disease, depression, and drug-taking in dozens of species. While consulting with veterinarians at the Los Angeles Zoo, Natterson-Horowitz realized that the animals were suffering from the same problems as her human patients, so she started investigating such similarities, quickly finding that pigs had eating disorders, wallabies got stoned, and jaguars battled breast cancer. Indeed, because culture wasn’t getting in the way, veterinarians were actually learning more about sex, addiction, and mental illness than their human counterparts, and — despite two centuries of growing separation between human and animals doctors since the dawn of the combustion engine — there was way too much complementary science being left on the table. The result is an entertaining and insightful series of anecdotes, bolstered by the latest in medical and veterinary science, arranged in chapters that focus on specific diseases and disorders from infection and fainting to self-injury, adolescent aggression, and obesity.

Along the way, Natterson-Horowitz enlisted the writing help of Kathryn Bowers, who was raised in Goleta and is the daughter of Arthur Sylvester, a respected professor emeritus of geology at UCSB. After graduating from high school, Bowers attended Stanford University, worked as an editor for The Atlantic Monthly in Boston, and then set about living all around the world, from New York and Washington, D.C., to London, Moscow, and Los Angeles, “the big bad city” where she’s resided for the past 13 years with her journalist husband and her daughter. I learned as much during two recent telephone conversations with Bowers: once while she was in Seattle on a book-related visit, the other from her home in L.A. What follows is an edited mash-up of those chats.

Tell me about your Santa Barbara upbringing, or were you in Goleta? It was Goleta — Goleta pride! I went to Dos Pueblos and Goleta Valley Junior High. I grew up running around Stow Park and Lake Los Carneros, and really loved growing up there. The longer I’m away, the more excellent it seems. It was a nice childhood.

Did you have a lot of pets growing up? The main feature of my childhood was that my sister and I were in 4-H and we raised rabbits. That was one thing I understood at the time but appreciate even more as an adult: the rural nature of Goleta and the ability to do something like that, to have rabbits in our backyard. I was like a city girl, but I had country surroundings. We had a dog and a cat, which we adopted from the shelter on Turnpike. We had hamsters and hermit crabs. We had very tolerant parents.

I know what happens with pigs in 4-H, so did you harvest the rabbits? We were doing rabbits for show. You could go into meat rabbits, but I was doing show rabbits.

So they were pretty rabbits? The breed was English spot, and they’re perfect for an 11- or 12-year-old girl. They have this eyeliner around their eyes, and a beauty mark, and a stripe down their back, and spots on the side. They’re very pretty rabbits. There was some sort of county-wide competition, and I won “Best in Show.” I still have the trophy. It is one of my prized possessions.

Did you always feel that humans had some deeper connection to animals? I always had a sense there was some connection there, but I don’t think I quite understood how deep the connection goes. That has been the most eye-opening part of writing this book: understanding that at the molecular, genetic level, we have the legacy of our evolution. I find that really fascinating. It’s something that I hadn’t thought that deeply about before I started writing the book, and now I think about it every day.

How’d you get interested in health and science journalism? A mutual friend introduced my coauthor and me, and Barbara started telling me about her experiences at the zoo — she was a human cardiologist who was a consultant at the L.A. Zoo. It sounded so interesting, so we started interviewing more and more, and it turned into the book. That was my introduction to health and science and environmental writing.

And my dad is a geologist at UCSB, so I have an interest in nature and evolution and science from my household while growing up.

He must be thrilled that your book is causing a stir in the science world. He’s really into it. He’s been supportive all the way through writing it, and also growing up.

What influence did he have in your childhood? Most geologists are either born naturalists or they become naturalists through their training. That was really influential growing up. I went on a lot of field trips with him. He would point out the very small things on the ground and also the giant scope of geology — entire mountain ranges and landforms. I felt like I had a micro and macro exposure to the Earth.

Also the idea of the Earth being very, very, very old, that made you think of humans and humanity in a different way when you appreciate how old the mountains are. I have really strong memories of visiting his office at UCSB — there were seismographs, which were fun to look at, maps on the walls, and all of these professors bustling around in their big boots and their beards, doing important work.

The book explains how doctors don’t talk with veterinarians anymore as they once did a century ago. Was that a conscious effort? I think it’s more the byproduct of specialization on the human side and then also the urbanization that started happening 100 to 200 years ago. The combustion engine worked animals out of the daily life of most people.

There is a little bit of a professional, perhaps, rivalry — well, it’s more like a separation between vets and human physicians. They started taking separate paths, and now they rarely communicate. But there are areas where they collaborate, and there are movements trying to bring them together. We’re hoping to galvanize that with this book.

What’s the reception been? We’ve had a really good reception. We weren’t quite sure how the human side would take it, but most physicians who we run this by are interested and receptive to it — just to realize the science we are leaving on the table by not talking to doctors that are taking care of these same diseases in animals and people. There’s cocker spaniels with breast cancer, orca whales that have Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and the behavioral aspect is also really interesting.

As someone who is neither a physician nor a veterinarian, it was eye-opening. It opened my mind to the idea that we’re really connected and health is really connected, not just to the other humans around us, but to our pets and even wild animals.

You’ve got great stuff on penises and stoned wallabies and toad-licking cocker spaniels. What did you find most fascinating? [Laughs.] Well, we did call that section secretly the penis-orgasm section. I had never stopped to think that even something like an erection has to have evolved from somewhere and that we have ancient ancestral ejaculators — it didn’t just spring forward into human form.

For me, the connections we have behaviorally were maybe most fascinating. We tend to think of psychology and psychiatry as so uniquely human, and we put so much pressure on us as having big human brains. But injuring ourselves, getting obese, suicidal behaviors, and risk-taking in adolescents — every one of those things can be found in other species. That means they aren’t necessarily your fault or a condition of being human. Plus, disease is not uniquely human, and there is something liberating in that.

In terms of examples that really surprised me, probably the idea of eating disorder was most interesting to me. That’s so very, very human. It always seemed to be linked to body image and seemed so conscious, but we learned that pigs can get self-starving syndrome during times of intense anxiety, especially social anxiety. Some pigs respond to stress by stopping eating, and sometimes they go on to starve themselves to death. And there are veterinarians who see this behavior and try to combat it.

We’ve evolved to eat on this planet for more than two billion years, and not eating is kind of dangerous, so we’ve evolved really complex behaviors to eat in a dangerous world. One is if you have a predator around, it’s a good idea to stop eating. So the idea that eating could be linked to fear of predators and predation responses — that could be a whole new way for psychiatrists to view eating disorders.

A lot of your book has some resonance with evolutionary psychology, which I studied at UCSB in the 1990s, and teaches that, because our behavior is a product of evolution, we are Stone Age animals running around in an urbanized world. But your book takes that even deeper. One thing that Barbara and I talk about is that anthropology and evolutionary psychology seem, like a lot of other human studies, to look a little bit less into the evolutionary timeline. They look at other ancient human beings, the hominids, for answers and stay around the great apes and primates.

But we say we should look further left for these much more common ancestors. We’re so used to looking at differences, trying to find the one little thing that makes us human, but there are vast similarities, including with ancient animals like dinosaurs and other animals that have been evolving, like insects. There’s even crossover with plants.

What action or effects do you hope comes from Zoobiquity? There are several of them. There’s already a lot going on in terms of cancer treatment and some cures pioneered by veterinarian-physician collaborations.

There’s also a lot being learned about obesity and how we eat. If veterinarians saw a group of animals getting fat, they’d never say, “Oh they have no willpower.” They’d say, “What’s going on in their environment to make them get fat? Is there too much food? Are they relaxed?” Diet gurus say you’re on your own, that it’s all about you and your mindfulness, but there’s a lot to be said about looking at obesity as an environmental issue.

Also, just the idea of a medical education that brings together veterinary students and human medical students to collaborate, starting that conversation between physicians and veterinarians, would be educational and, I hope, would educate patients, too.

It does seem as if people have reached a point where we’re happy to learn that we share a lot in common with animals, despite what we’ve been told over the years. We’ve been very, very lucky. It’s a new way of seeing ourselves. Even though, obviously, veterinarians have been doing this awhile, there’s something about putting it all together that the world’s ready to hear.

4•1•1

Kathryn Bowers and Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz will sign copies of Zoobiquity on Tuesday, August 28, 7 p.m., at Chaucer’s Books. For more information, see zoobiquity.com.