Anger and Politics

Stoking the Fire Can Lead to a Loss of Rational Thought

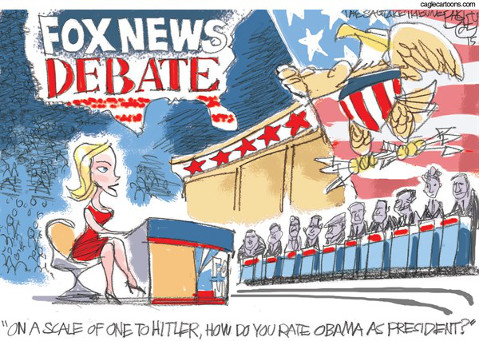

How do we define anger? “A strong feeling of annoyance, displeasure, or hostility,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary. Anger has its place on the map of today’s political landscape with the upcoming presidential election in 2016 providing the backdrop. There is distinct displeasure shown by a significant amount of people who feel disenfranchised. It is not abstract but much more existential. The pulse can be felt in the rhetoric of the politicians and certainly the diatribes of right-wing talk radio. There are people like Donald Trump who can stoke this anger with visceral comments that are regarded as incendiary toward people of color and women. Still it is transparent that Trump could not have conjured up an anger that was not already there.

The candidates running for president in the Republican Party have tapped into this anger. They have tried to elicit xenophobic reactions from their supporters from 2010 with Tea Party phrases like “We have come to take our country back” to challenging the birth certificate of the President of the United States. In 2015 the immigration issue and blaming immigrants for the country’s woes hearken to a time in the early 20th century. Deep prejudices against European immigrants in that time are now transferred to refugees from Mexico and Central America who have come across our border looking for a safe haven and a better life. In recent days Donald Trump has announced an immigration plan that would deport more then 11 million people from our shores. And presidential candidate Scott Walker has advocated that those born of foreign parents in America should not have citizenship, thereby invalidating the 14th Amendment. Hostility has become a plank in the Republican platform.

So how do behavioral and public policy professionals regard anger and its role in decision making? In the International Handbook of Anger, Paul M. Litvak, Jennifer S. Lerner, Larissa Z. Tiedens, and Katherine Shonk of Harvard University write in their chapter “Fuel in the fire,” a portrait of angry decision makers. They look to see whether anger affects perceptions, beliefs, ideas, reasoning, and final choices. Quoting Aristotle at their conclusion, “Angry decision makers have a difficult time being angry at the right time for the right purpose and in the right way. Their emotional experience may hinder their ability to view a situation objectively and rationally.

It is this “harvest of anger” that many in the Republican Party reap to convince their base that they share their annoyance. For instance, Ted Cruz accused the party’s own Senate leader Mitch McConnell of lying, and we saw Rand Paul and Chris Christie matching verbal blow for blow in the debate over the libertarian privacy issue of government overreach on national security. And Scott Walker and Marco Rubio assured evangelicals that the life of the unborn should have supreme consideration over the life and well-being of the mother, and women should be forced to give birth even in cases of rape and incest.

And yet, issues that truly affect the lives of everyday people in the nation went unvoiced in their recent national debate. Income inequality, voter suppression, and a living minimum wage inspired hardly a murmur of protest or a sincere feeling of indignation. The U.S. is falling further and further behind other industrial democracies around the world, and still the GOP clings to the outdated notion of American exceptionalism. Further the collective outrage from the Democrat or Republican party over poverty, child hunger, and mass shootings in this country remain muted by the saturation of money in politics and special interests like the NRA.

In the coming months, the American electorate will be asked by the GOP to choose emotion over reason in an attempt to dissuade critical thinking from the science of global warming to the founding fathers’ core principle of separation of church and state. For those whose anger has created an obdurate perception, this strategy will prove effective. But when anger stays outside the voting booth and doesn’t “buffer indecision and risk aversion,” decision makers can choose a candidate who is willing to separate fact from fiction and pragmatism over angered ideology and tribal involuntary responses.