‘California 101’

UCSB Art, Design & Architecture Museum Surveys California Art, 1940-2016

Interest in the postwar art of California has been running high, at least since the Getty Institute’s Pacific Standard Time initiative that began in 2011. This current exhibit at UCSB, which primarily draws on the Art, Design & Architecture (AD&A) Museum’s permanent collection, delivers a sharp, informative, and thought-provoking version of what California has contributed to the art world since 1940. Curated by Rebecca Harlow at the request of art history professor Jenni Sorkin, who is teaching a course called Art in California: 1949-2016, California 101 travels the length of the state in pursuit of objects that represent the engagement of artists who have lived and worked here for a substantial period of time with the major issues and movements of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Car culture permeates the show, as only befits an exhibition whose title conflates our main coastal freeway with the idea of an entry-level college course. One concatenation of artworks in particular succeeds in articulating a vision of the automobile as cultural avatar. Audrey Simokaitis Sanders and her husband Jeff Sanders traveled up the 101 from Los Angeles to Ojai in the early 1970s. Audrey Simokaitis Sanders’s “Open March Zebra,” a painting-like construction from 1974 consisting of chicken wire wrapped in cloth and then dappled with black paint, hangs on the far side of the main space, propped at a slight distance from the wall in order to take full advantage of the way the dense weave of shadows it casts interacts with its crumpled, painted surface. An image drawn from nature — Sanders sees it as embodying the texture of sunlight through a latticework of moving leaves — “Open March Zebra” nevertheless partakes of the same black-and-white sensibility evident in Ed Ruscha’s “Main Street” (1990), which hangs elsewhere in the same room.

At the center of the room sits a vitrine full of scale model cars built by Jeff Sanders, Audrey’s husband. These “Plush Hummers,” as Sanders titles them, come in Mandarin Orange, Tangy Lime, and Delicious Apple, among other colors seemingly derived from the marketing of candy. Sanders served for many years as a chief fabricator in the atelier of Ed Kienholz, and the two magnificent examples of the Kienholz oeuvre in this exhibit are both on loan from the couple’s private collection of his work. “Sawdy” (1971), a car door modified to present a gruesomely ambiguous scene on the inside of a functioning roll-down window, presents Kienholz at the height of his powers, dictating the direction of a crucial stream of California art that continues down to today, most prominently in the grind-house Guignol sensibility of filmmaker Quentin Tarantino.

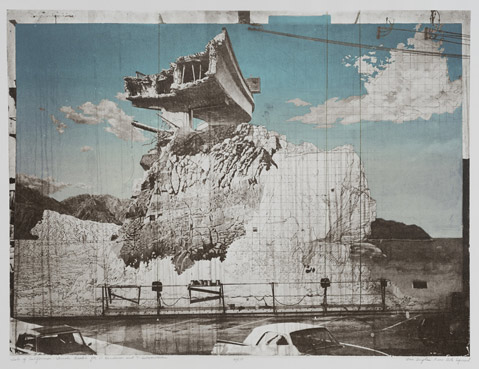

Curator Harlow has echoed this current in her choice of an image to represent the entire exhibit on posters and flyers. “Isle of California — Lunch Brake for V. Henderson and I. Schoonhoven” (1973) is a lithograph that’s all that’s left of a mural created by the Los Angeles Fine Arts Squad that once occupied a wall at the corner of Sawtelle and Santa Monica Boulevard. This postapocalyptic image of a fractured freeway overpass, which predates the Northridge quake by more than two decades, provides a telling reminder of the degree to which our concrete California reality is built on so much superficial sand.