Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself

Filmmakers Tom Bean and Luke Poling

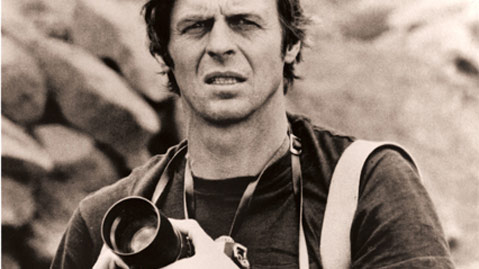

This portrait of participatory journalist George Plimpton features the biggest names in magazine journalism analyzing the late writer and his considerably legacy, from perfecting the Q&A form in his tenure at The Paris Review and penning perhaps the best work of sports journalism ever in Paper Lion to his friendship with Bobby Kennedy and lifelong struggle with acceptance amongst his peers.

Plimpton boxed, tamed lions, acted in Westerns, trapezed through circus tents, apprehended Sirhan Sirhan, did stand-up comedy, and hosted the most raucous parties on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, living perhaps a most enviable existence. This documentary does him well, but it also analyzes his sometimes conflicted and lonely life.

To get a better sense of the man and the film, I emailed filmmakers Tom Bean and Luke Poling some questions, and this is what they had to say.

First of all, for being the man who perfected the Q&A format, what do you think Plimpton would have thought about the emailed Q&A? It’s certainly not quite as cool.

Tom Bean: The Paris Review interview, which George helped create and develop, wasn’t the result of a single live interview session, but rather the culmination of months (and sometimes years) of interviews, correspondence, and editing that was done in collaboration with the writers they profiled. The goal was to have the subject say exactly what he or she meant about the craft of writing, and correspondence was (and is) a terrific way to achieve this. With some of the interviews, like Jack Kerouac, who was in poor health at the time, much of the final printed interview in the magazine was derived from letters between the writer and George. In short, I think George would like your style.

The film features a who’s who of magazine journalism. Was everyone eager to remember him as you filmed this doc?

TB: I never had the good fortune to meet George (I moved to New York the year after he died), but it seems clear that people loved being around him. I once heard someone refer to him as an “agent of joy.” When we called his friends and family, his peers, and even his rivals, they were generally very happy to talk about him with us — it seemed like they wanted to bring him back for a couple of hours.

Had Bobby Kennedy not been killed and won the presidency, do you think Plimpton would have served in his administration?

Luke Poling: If Kennedy had not died, been elected and offered George a position in the administration, I don’t know if George would have taken the post because I don’t think he would have wanted to leave his beloved Paris Review. He compared the thought of closing the magazine to losing an arm, so, I don’t know if he would have given it up so easily. And accepting the appointment would mean he also would have to give up reporting on the people and subjects that fascinated him. (You don’t see as many cabinet members on the trapeze as you would like.)

Why do you think he never wrote about the Bobby Kennedy assassination, which he witnessed from a few feet away?

TB: We got very lucky in our research to have discovered a recording of George’s interview with the LAPD after Kennedy’s assassination because it wasn’t an event that he spoke about often in interviews or that he wrote about in a specific way. (George edited a book about Bobby’s rise in politics, but it wasn’t from Plimpton’s perspective.) Plimpton and Kennedy were close friends (and George was an big supporter of his campaign for the Presidency), so I can only assume that witnessing Bobby’s death was deeply traumatic and not something he wanted to revel in or comment on publicly.

Near the end of George’s life, he was given a significant offer to write a memoir (a book I would have loved to read), and we were told by his friends that he was nervous and even emotional about idea of writing about Kennedy’s death. When I read his essay “The Man in the Flying Lawn Chair,” a story which shows a person soar (figuratively and literally) to great heights and then take his own life, it makes me think that George could have faithfully captured in prose the trauma and emotional depth of losing his friend — if only he’d lived long enough to write it.

The only thing I might add to Luke’s answers is in response to your question about the Kennedy government. George was a fireworks enthusiast and was appointed by Ed Koch as the unofficial Fireworks Commissioner of New York City (a post he unofficially held until his death in 2003). If Kennedy had created a cabinet position in this vein (Secretary of Fireworks and Celebratory Displays, for example- FCD for short), I think George would have seriously considered the job.

Do you think he died a satisfied man, one who had moved past being thought of as a dilettante?

LP: That’s one of the central questions of the movie and we tried hard to show both sides of the argument. I think that, at the end of the day, George did exactly what he wanted and died incredibly satisfied. A few years before his death, Plimpton was inducted into the Academy of American Arts & Letters as a writer, and not as an editor.

It’s an important distinction because he certainly could have been inducted as an editor. But he was honored for his writing which features his unique, witty and self-deprecating style. Ken Burns told us that he thought people would still be reading Plimpton in 50 years for the same reason people still read Mark Twain today: He’s a funny, entertaining writer. And I think one of George’s ambitions was to be a

good writer.

I think this shows that he most certainly was.

What about his parents? Did he meet their expectations?

LP: I don’t think he met their expectations, but I don’t think he was living his life to please them. He did what he wanted to do. And he made a great success of it. The mere fact that The Paris Review is still publishing after 60 years, Paper Lion is still in print 50 years after it first came out, and we’re still talking about George 10 years after he died, shows he was a great success.

I think he followed his own muse which must have made for some difficult conversations over the Thanksgiving table. Maybe he didn’t meet his parents expectations, but what parent expects their son to play himself on “The Simpsons,” invent a new way to conduct an interview or play horseshoes with the President of the United States?

Plimpton! screens on Sun., Jan. 27, 10:40 a.m, at the Metro 4, and Thu., Jan. 31, 11 a.m., at the Lobero Theatre.