Ghost Salmon

“I would ask you to remember only this one thing,” said Badger. “The stories people tell have a way of taking care of them. If stories come to you, care for them. And learn to give them away where they are needed. Sometimes a person needs a story more than food to stay alive. That is why we put these stories in each other’s memory. This is how people care for themselves. One day you will be good story-tellers. Never forget these obligations.” – Barry Lopez, Crow and Weasel (North Point Press, 1990)

To recover our sense of the wildness of the deep blue ocean, we need to create new stories of our place and region. In stories of place, we human beings find new symbols and galvanizing forces to unite us with the places we inhabit. For millennia, maritime stories have emphasized the need to return to the ocean as a source of wildness and nourishment for the human soul. Poets turn to the ocean not only for food or even aesthetic inspiration but also for what Henry David Thoreau referred to as “the tonic of wildness.”

In one ancient maritime myth, for instance, an albatross was referred to as a representation of the soul of a sailor lost at sea. An albatross is a central emblem in “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In Coleridge’s poem the bird is a metaphor for a burden or obstacle (as reflected by the line “an albatross around their neck”), and in the poem a mariner is punished for killing an albatross. Throughout history, sailors who caught the bird let them free for fear of reprisal from the sea.

Stories of animals can teach human beings about the connections and relationships that exist across the landscape and seascape. We need to look to other animals as surrogates or totemic forces that can support change in our behavior. Other animals can represent unifying forces that re-connect diverse places and peoples to forge a more sustainable future.

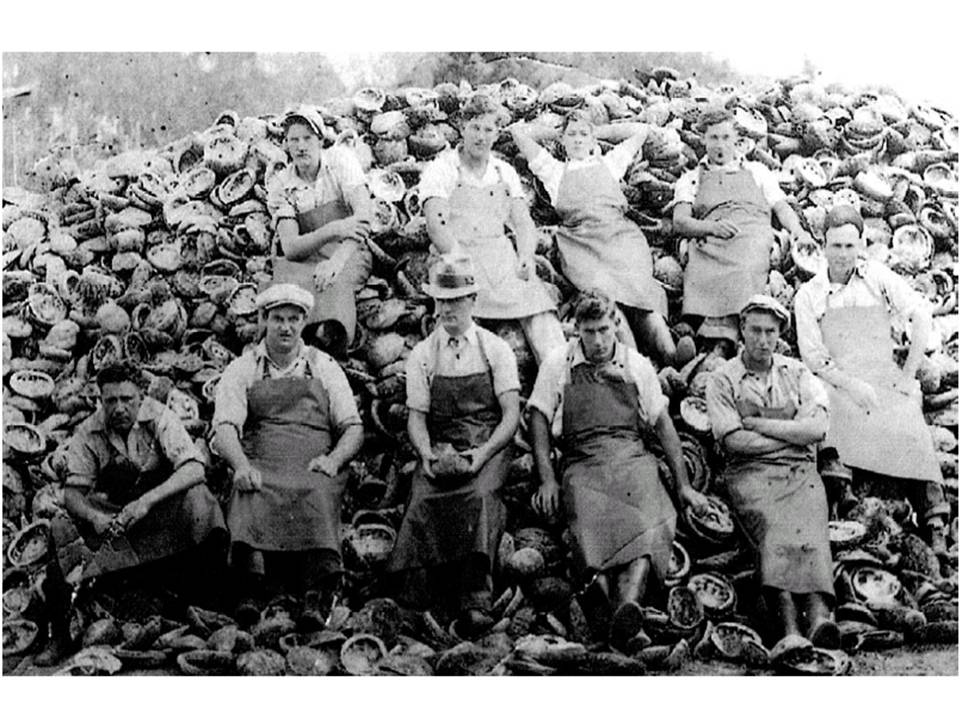

Before the early 1970s, the Channel Islands were home to 1,000-5,000 white abalone per acre. Highly prized for their tender white meat, white abalone were harvested in intense commercial and recreational fishing activity that developed during the 1970s, then quickly peaked and crashed as the abalone became increasingly scarce. The fishery for white abalone closed in 1996. In the 1990s, less than one white abalone per acre could be found in surveys conducted by federal and state biologists. The rarity of this species within its historical center of abundance prompted the National Marine Fisheries Service to list it in 1997 as a candidate species under the Endangered Species Act. In May 2001, the white abalone became the first marine invertebrate to receive federal protection as an endangered species. The collapse of this species is a tragic story of a natural world disappearing before our eyes; it is a story of lost opportunities to preserve available resources and the life-giving values of the sea.

Another animal on the verge of biological collapse in our region is the wild southern steelhead salmon. The genetics of diverse wild steelhead salmon that exist along the west coast of the United States have a common characteristic – they are the genetic offspring of our south coast salmon who survived glaciation during the Holocene several thousand years ago, and migrated up the Pacific coast as the ice retreated.

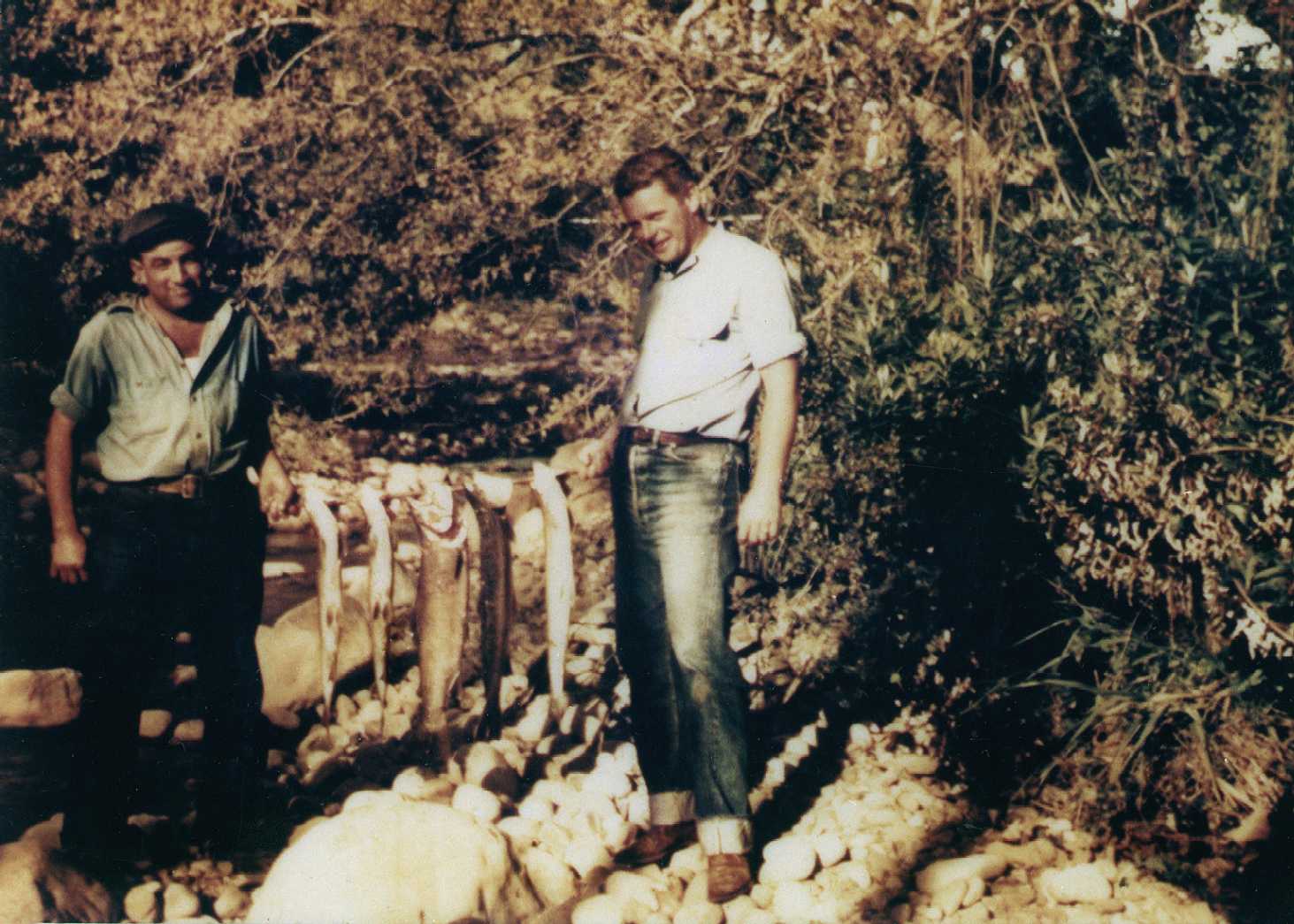

There are stories of fishers using a “Portuguese sling” (a pitch fork) to catch the steelhead salmon as they swam up the Santa Ynez River to spawn. There is no greater indicator species for the health of coastal watersheds and the marine environment than the presence of a wild salmon run. Our reliance on large industrial hatcheries to replace the presence of wild salmon masks the plight of these endangered species. There is no engineering solution or quick technical fix to the loss of salmon. The loss of habitat to urbanization and industrialization during the past one hundred years is the primary factor that has contributed to the loss of wild southern steelhead.

Imagine the Los Angeles River full of salmon more than a hundred years ago. Much of the Los Angeles Basin was a vast rolling plain of grassland scattered with oak trees. There were wild southern steelhead salmon that swam the creeks and rivers of the basin. In low-lying areas between hills and bluffs, the Los Angeles River and dozens of lesser streams meandered through broad valleys to the sea. They carried so much fresh water to the sea that when explorer Juan Cabrillo first anchored in San Pedro Bay in 1542, he could haul fresh water, which floats on heavier seawater, aboard ship with a bucket.

Coastal areas like Malibu and Santa Monica were a mixture of sand dunes, sagebrush, scrub, fresh and saltwater marshes, and lagoons. These areas were home to migratory birds, dozens of kinds of mussels, tuna, trout, halibut, ling-cod and sardine. Thousands of porpoises, sea lions, sea otters, and seals lived in colonies along the coast. In the winter, much of the coastal plain was a vast lake, stretching from the silt-rich highland of present-day Culver City west to the ocean, and fresh water springs flowed year-round in Beverly Hills.

During heavy rains, torrents from the mountains would flood the area, and the swollen Los Angeles River would change its course, sometimes emptying into the Bay at Ballona Creek, sometimes emptying into San Pedro Bay, always depositing rich, dark soil across the plain. The Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers once met to form one of the largest wetland ecosystems in California. In the early part of the 19th Century, the wetland of the two river systems was estimated to be as large as 18,000 acres. By the early 20th Century, the wetland and rivers of the basin were destroyed, filled and paved over.

Despite this type of economic growth and development, the southern steelhead survived. The steelhead is a resilient animal that has adapted to our turbulent Mediterranean climate of floods, fires, and major storm events as well. The continued existence of wild southern steelhead will depend on how the citizens and inhabitants of our coastal region protect and restore their habitat along creeks and rivers.