Thousands of Plaintiffs Added to Refugio Oil Spill Case

Litigation Follows Footsteps of 1969 Union Oil Spill Attorneys

The consequences of the Great 1969 Oil Spill in Santa Barbara go beyond the giant nudge it delivered to assert a need for tighter regulation of the oil industry. It also laid out the game plan for lawsuits. Today’s legal heavy hitters include Santa Barbara’s Barry Cappello, who cut his teeth as city attorney recovering from Union Oil for the coating of the beaches, the harbor, and facilities with thick, heavy crude. The most recent development in suits stemming from the 2015 Refugio Oil Spill — the certification of private property owners as a class that may sue Plains All American Pipeline — was a strategy first pursued in part by Stan Schwartz, one of the big backers of the fledgling Legal Aid in Santa Barbara at the time. Schwartz, who died in 2015, represented renters harmed by the 1969 oil spill, who were ultimately included in the class action brought by property owners in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties. But determining how to assess damages was quite a struggle, recalled John Warnock, a partner with Schramm & Raddue, which represented the property owners.

The 1969 cases were soon moved to federal court in Los Angeles, where the Refugio cases are also being heard. So far, Judge Philip S. Gutierrez has affirmed that fishermen and fishing enterprises are a class injured by the Refugio spill, as well as oil industry and platform workers thrown out of work by the spill and subsequent closure of the broken pipeline, which has yet to reopen. Cappello pointed out that even in 2010’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 — which was settled by the U.S. government for $20 billion — oil workers were not allowed to be a damaged class of plaintiffs. Cappello’s law firm, Cappello & Noël, is pursuing the litigation with three others: Audet & Partners; Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein; and Keller Rohrback. The latter two sued Exxon in the 1989 Valdez case.

Another precedent set by the 1969 spill was the ability of governments to recover revenue losses, said Cappello. He said he’d fought Union Oil to a settlement for $4.5 million for the damage to the city’s shore and facilities; it was only later that the California Legislature passed laws codifying such recoveries. This time around, the City of Santa Barbara settled with Plains a year or two after the spill for $2.5 million. City Attorney Ariel Calonne explained that the city hadn’t suffered much property damage but considerable reputational harm that reflected in a drop in tourism.

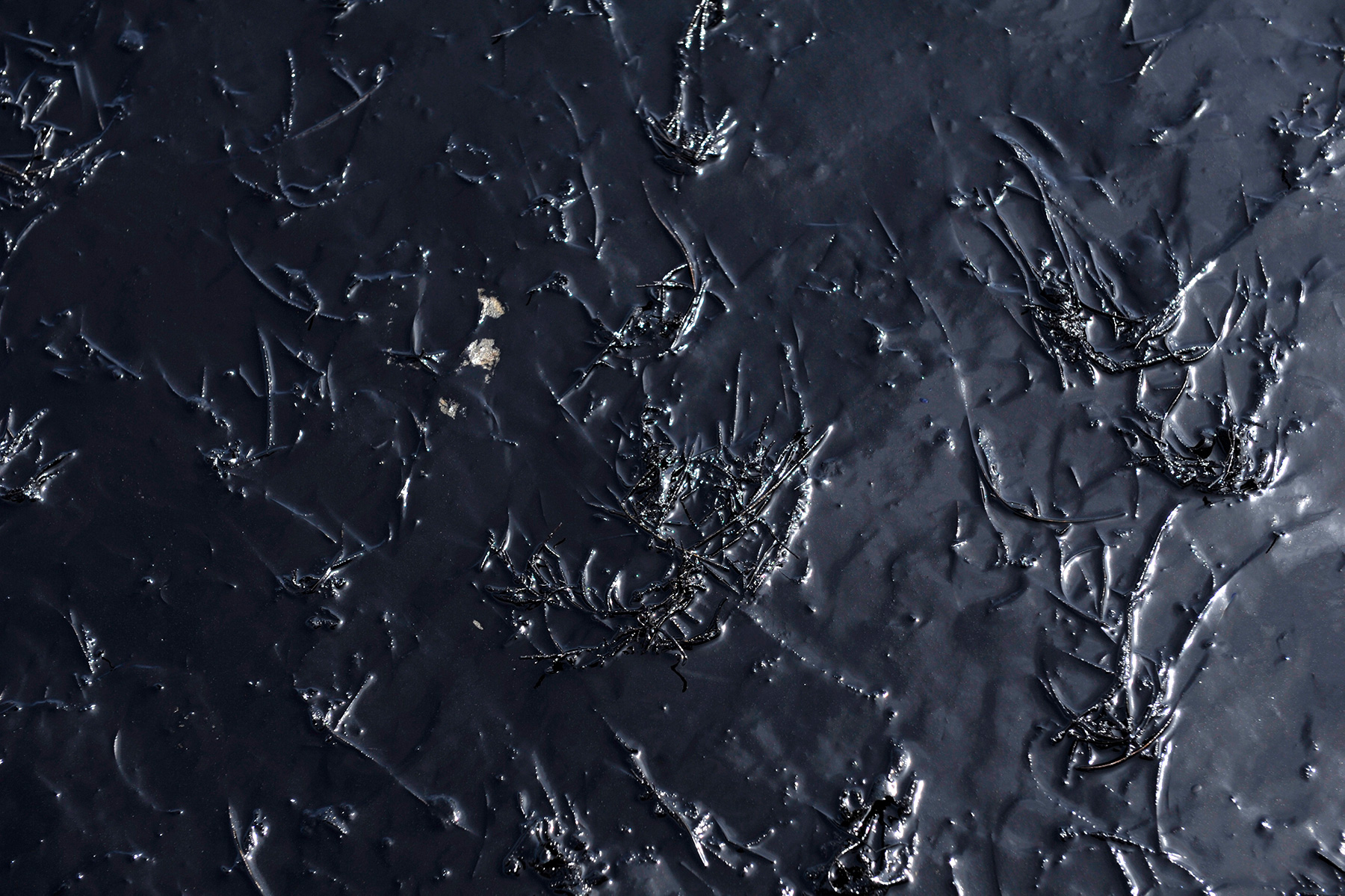

Plains, which will soon be on trial in Santa Barbara Superior Court on 15 criminal counts of knowing discharge of pollutants, may face as many as 5,000 class-action litigants in federal court for spoilage to land. Two experts who analyzed where the spill likely went — from Hollister Ranch to Manhattan Beach — and the economic damage to real estate convinced Judge Gutierrez that private landowners had been damaged as a class. Cappello said even tenants and easement owners, as at Bonnymede and Santa Barbara Shores, are included. A couple of his clients are Miramar Beach residents who pay a higher rent to live at the beach, he asserted, and suffered a loss.

“Plains had argued that the class definition was too vague,” Cappello said, of the addition of private property owners, renters, and easement owners as a class. “But with the last set of briefings, the judge said, ‘I don’t need another hearing. I’ve heard this so many times,'” when he certified the class. “And,” Cappello went on, “the amount of oil that spilled? It’s being determined by the experts, but it may be as high as five to eight times the Plains estimate.” There is so far no timeline on when the class action suits might have their day in court.

Editor’s Note: This story was changed on April 25 to remove the reference to $5.5 billion in damages paid in the Deepwater Horizon spill. That was the Clean Water Act portion; the total settlement to the U.S. government was $20 billion.