Bellosguardo: A Legacy in Limbo

Foundation Leadership Accused of Mismanagement, Favoritism, and Neglect

In May 2011, the reclusive heiress Huguette Clark died, leaving her grand East Beach estate, Bellosguardo, to a public charity for the purpose of fostering the arts. Giving her palatial summer home to the Santa Barbara community was, by far, the largest single gift of her $300 million fortune. Clark hadn’t visited the 27-room mansion, with its extensive art collection, in more than 60 years, and in recent decades, very few people had ever seen inside. It stood on the cliffs overlooking the ocean, a bit of a mystery to those living in the city below. But after her death, it became clear that Clark had wanted Bellosguardo to be publicly cherished as a lasting benefit for Santa Barbara and preserved for the appreciation of art everywhere.

Three and a half years after the formation of the Bellosguardo Foundation — a 501(c)(3) nonprofit registered in New York and operated out of Santa Barbara — Clark’s dream is no closer to being realized. Instead, the mystery surrounding the property has intensified, and a pall of secrecy has gathered over it. In apparent violation of its own bylaws, the foundation’s board of directors has not held a single formal meeting, multiple directors have resigned, and its local leadership has had to fend off allegations of mismanagement, favoritism, and neglect.

Over the last six months, the Independent has directed questions to the foundation — which now controls more than $95 million in Bellosguardo property, artwork, and cash. All have gone unanswered. This lack of information that has led many in the Santa Barbara community to rely on baseless rumors has also generated legitimate concerns about the future of the estate. This article attempts to address what is factually known about the foundation and its mission, and what is going on behind Bellosguardo’s beautifully carved wooden doors. The information presented here was gathered from public documents and more than two dozen interviews with people intimately familiar with the property and organization. Many of them spoke only on the condition of anonymity.

Trouble from the Start

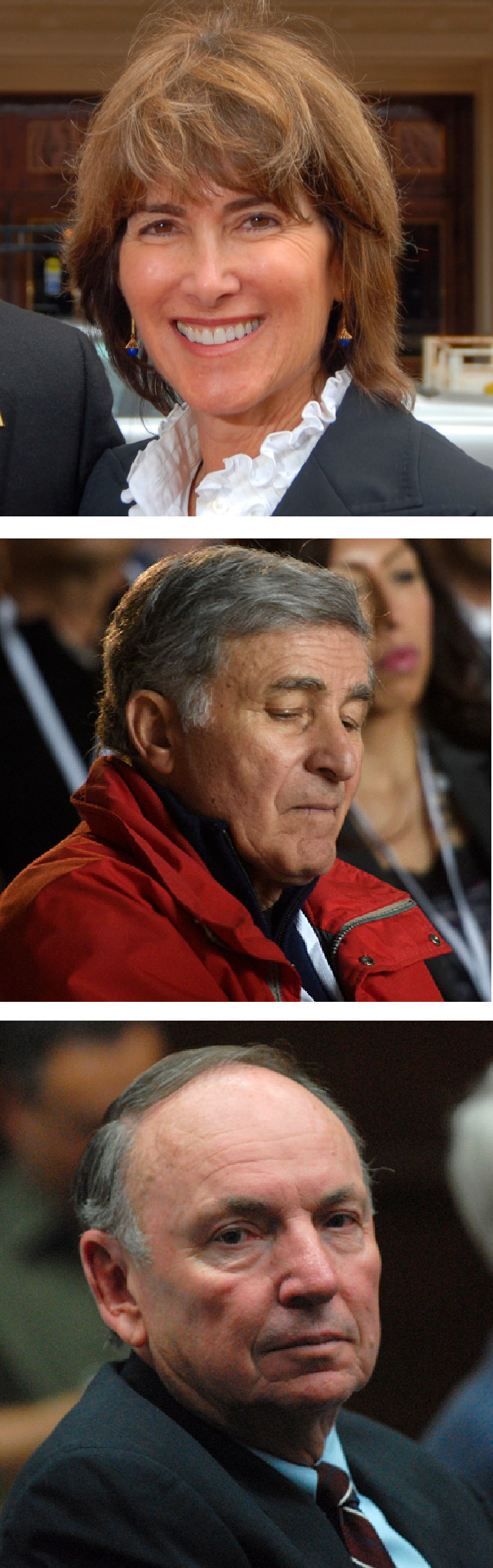

Conflict-of-interest allegations have plagued the Bellosguardo Foundation since its inception in September 2014. Per the settlement agreement of Clark’s will, then–Santa Barbara mayor Helene Schneider was asked by the New York Attorney General’s Office to nominate 19 members to the foundation’s new board of directors. In an email exchange with the Independent last week, Schneider said that because the nomination process was “extremely time-consuming,” and because she was carrying it through as a private citizen, not a city government representative, “I asked my consultant Jeremy Lindaman to assist.”

Throughout his career as a Santa Barbara political consultant — working on the election campaigns of Schneider, former mayor Marty Blum, former councilmember Bendy White, and Sheriff Bill Brown, among others — Lindaman, who’s in his thirties, has cultivated a reputation as a formidable, skilled, but antagonistic operator. Many of his professional relationships have ended badly, and a wide range of politicians and public figures have described Lindaman behaving as a bit of a bullyboy.

While interviewing potential boardmembers, Lindaman contacted former mayor Hal Conklin, a longtime civic activist in Santa Barbara’s art and philanthropic scene. Conklin described Lindaman as brash and bizarre. “As I recall, Jeremy said to me, ‘You’re going to be on the board, you’re going to contribute $500,000 [to the foundation], and you’re going to endorse Helene.’” At the time, Schneider was preparing to announce her bid for the 24th Congressional District, a race she would ultimately lose to Salud Carbajal. Schneider termed off of the Santa Barbara City Council earlier this year and now works as both a regional development manager for Cal State Channel Islands and a regional coordinator for the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness.

Conklin was put off by Lindaman’s demands, to put it mildly. While nonprofit boardmembers are often asked to gift funds to the organizations they oversee, the half-million amount Lindaman expected was “insane,” said Conklin. More worrisome was Lindaman’s insistence that Conklin publicly endorse Schneider’s bid for Congress. “He was intermingling things that I thought looked bad,” said Conklin. Other individuals contacted by Lindaman to be on the board made similar accusations.

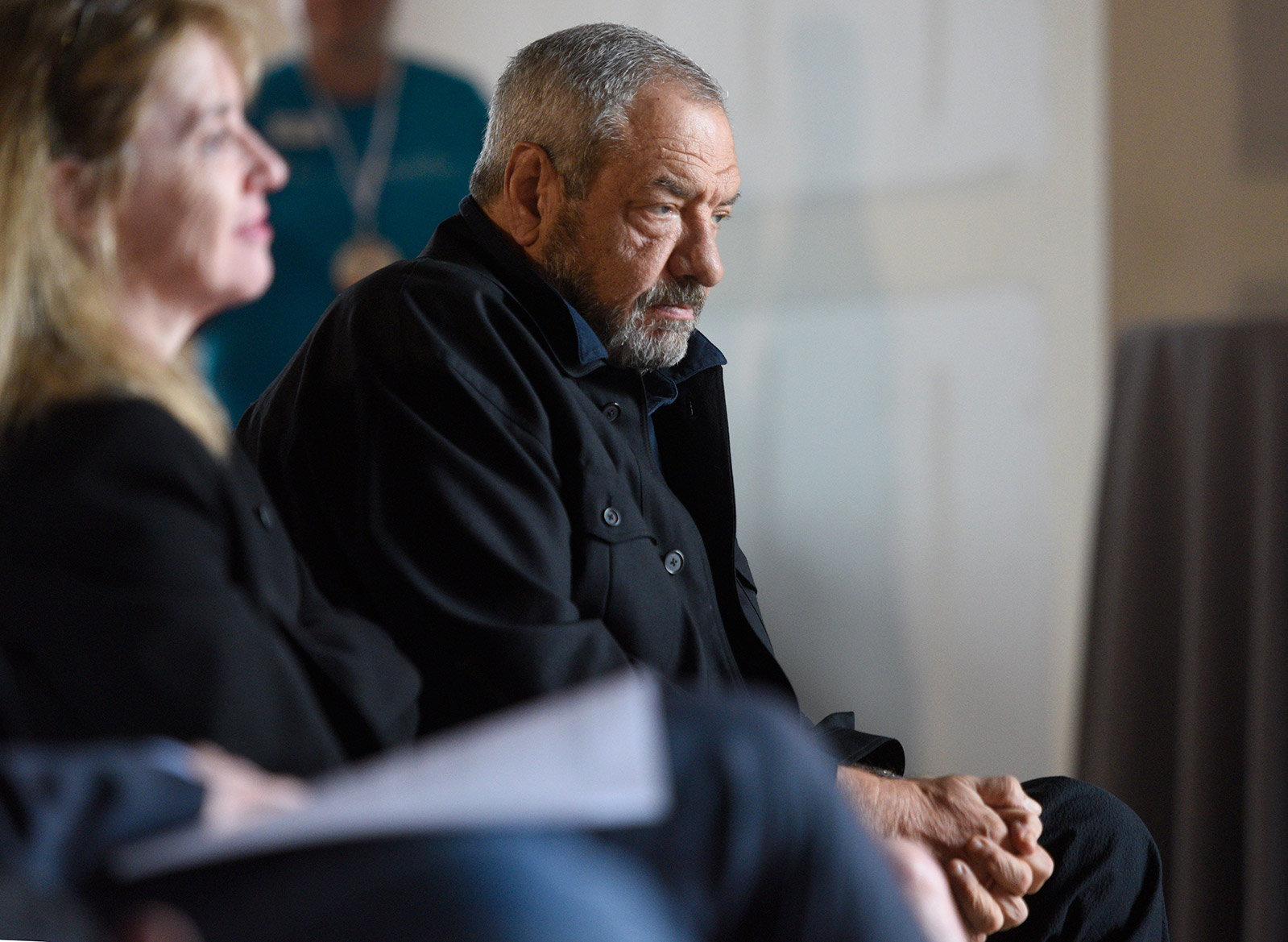

Ultimately, Schneider assembled a list of directors that was approved by the New York Attorney General. Several members were specifically requested in Clark’s will, including her half-great-grandnephew, Ian Devine; a representative of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, attorney Charles Patrizia; and Jim Hurley, who had been Clark’s Santa Barbara attorney. The other members were mainly prominent Santa Barbarans, including Robert Lieff, Anne Towbes, Pete Jordano, Morrie Jurkowitz, Joan Rutkowski, Perri Harcourt, Diane McQuarie, and Ron Pulice. Famed television producer Dick Wolf was chosen as chair, with Jack Overall as treasurer and Sandra Nicholson as secretary. One of the board’s first orders of business was to elect Lindaman as president.

That decision drew sharp criticism from experienced nonprofit professionals and donors in the community. What, they asked, were Lindaman’s qualifications for running a complicated, multimillion-dollar nonprofit? Conklin noted that most directors of major Santa Barbara organizations were chosen after nationwide searches and brought with them PhDs and decades of experience. “Jeremy has none of that,” he said.

The foundation’s 2015 and 2016 tax returns (the most recent available) state that Lindaman received a salary of $110,000 and $80,000, respectively, for approximately 10 hours of work a week. A minimal amount of income was reported in that time, just more than enough to cover his salary. The 2015 record shows Clark’s estate, through the New York Public Administrator, contributed $150,000 to the foundation. In 2016, the estate gave another $30,000. Wolf contributed $50,000, and Nicholson gave $5,000. Unexpectedly, the WWW Foundation, an arm of a South Pasadena wealth management firm, also donated $20,000. Its spokesperson, Pegine Grayson, said she was “really not at liberty to discuss that grant.”

Lindaman declined to directly answer any of the 36 questions submitted to him by the Independent regarding the foundation’s finances and operations: What does your job entail? When and how was your salary decided? What have you accomplished in your time as president? Have you drafted any strategic plans? Have you organized any capital campaigns? Have you contacted any potential arts partners? And so on, including a number of questions concerning his personal and professional relationship with Helene Schneider.

Instead of addressing the questions, Lindaman said he would only provide a general statement on the condition that the Independent would print it in full. The statement is below. Schneider also declined to address a similar list of questions; instead, in a written response, she charged that any accusations of impropriety on her part were “a tool some people with questionable motives are clearly using to attempt to smear me personally and politically.”

Best-Laid Plans

Both Lindaman and Schneider blamed the Bellosguardo Foundation’s inactivity over the last three and a half years on a pending decision by the IRS whether to forgive $16 million to $18 million in gift-tax penalties Clark owed at the time of her death. Attorneys repeatedly advised them not to speak publicly about the process, they claimed. Now that the penalties have been waived, and the estate is finally out of legal limbo, “The Foundation can now begin more publicly discussing the options for the property’s use,” Lindaman said in his statement.

Sources within the foundation say Lindaman was not directly involved in the negotiations and that only New York attorneys interacted with the IRS. They also noted that the 2013 will settlement was premised on the expectation that the IRS would waive the penalties because the agreement mostly benefited charities. For its part, the IRS said it could not comment due to federal disclosure laws.

If the IRS delays prevented the foundation from making any major decisions, many knowledgeable observers wonder why the nonprofit — and Lindaman’s salary — was not put into abeyance until the tax issue was resolved. Or if Lindaman was working, why have there been no art appraisals, feasibility studies, or other preliminary spadework?

In its 2014 founding documents, written and signed by Lindaman under penalty of perjury, the foundation lays out its vision to transform Bellosguardo (meaning “beautiful lookout” in Italian and pronounced BELL-os-GWAR-doe) from a dusty relic into a modern arts haven. Its first task was supposed to be to develop a “long-term plan to create a museum experience for the visiting public, which will include ticketed admissions to the property.” Designs were to be drafted to upgrade amenities, improve access, and coordinate parking.

Lindaman also promised conversations would begin with “charitable and educational arts institutions that can lend expertise, knowledge, and advice to the Foundation, as well as facilitate exhibitions.” He said he would explore the possibility of forming a partnership with the nearby Music Academy of the West to bring live performances to the property’s five-acre lawn in the spring and summer.

None of these critical steps seems to have happened. “The Museum has had virtually no contact with the Foundation over the past three years,” said Santa Barbara Museum of Art Director Larry Feinberg. “There is some feasibility that Bellosguardo could be another venue for art viewing, but a great deal of renovation would need to take place before this could occur,” Feinberg went on, “including means for security, ADA compliance, climate control, and long-term maintenance. With these improvements in place, the Museum would be willing to put some of its permanent collection on view there.”

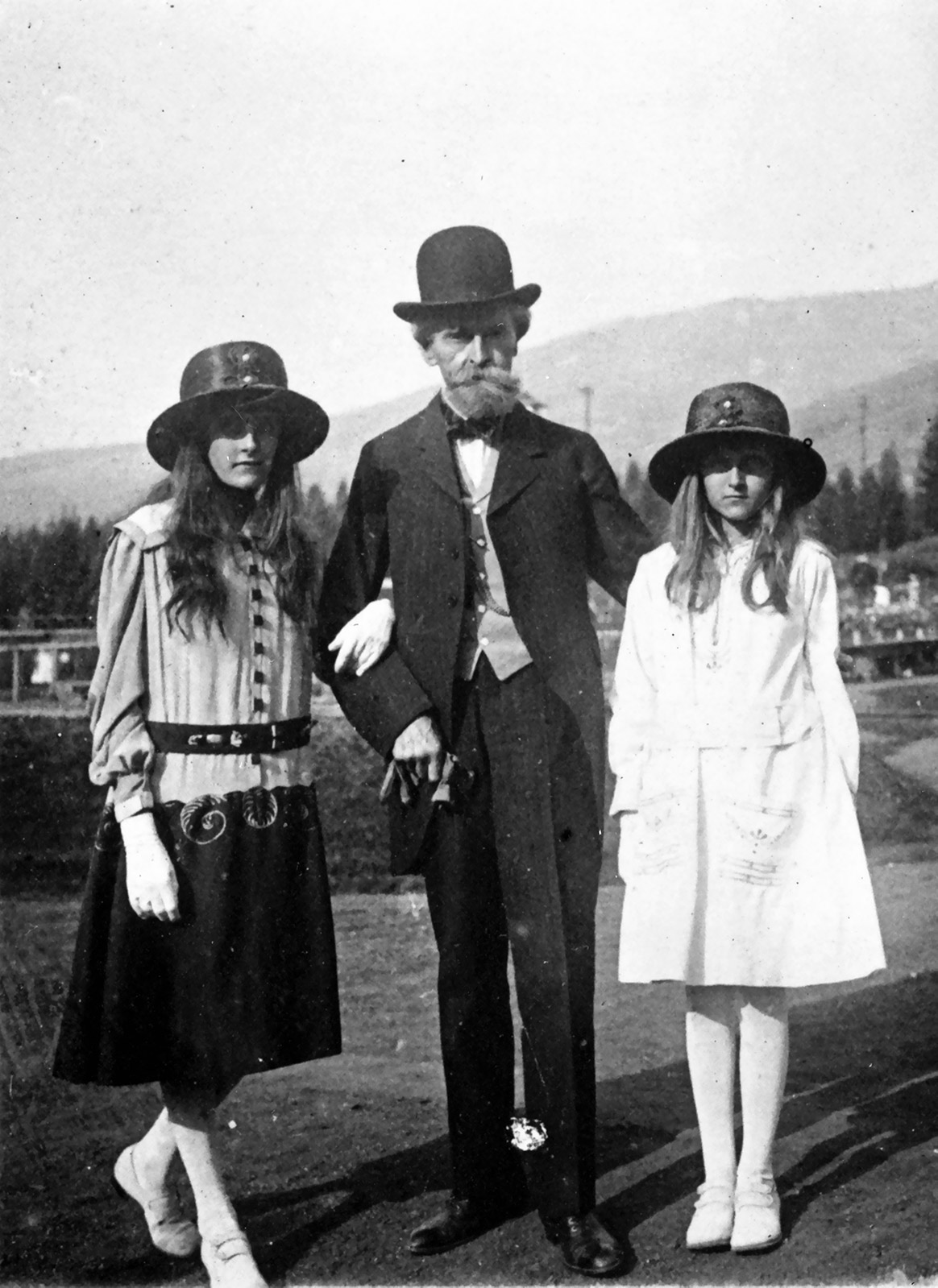

Relatively few works of great value or historical significance currently hang on Bellosguardo’s walls. A number of the paintings are portraits of Clark and her sister, Andrée, by a Polish artist named Tadeusz Styka. “The house is full of portraits of Andrée, paintings sometimes two to a room,” notes author Bill Dedman in his biography on Clark, Empty Mansions. “Her deep-set eyes are everywhere.”

The Music Academy of the West is also unaware of any collaboration that the Bellosguardo Foundation may be planning, according to Ana Papakhian, vice president of marketing and communications. “Bellosguardo is a property within our neighborhood, so we hope it is put to good use for our community.”

Mayor Cathy Murillo explained the City of Santa Barbara, along with the Coastal Commission, has land-use authority over the property and that the foundation has not filed any project applications. “I have no contact with the foundation,” she said. “No one from the estate, family, or foundation has ever tried to contact me.” But how wonderful it would be, she said, to one day open the house and grounds to the community. “And I know Huguette Clark wanted to support the arts and honor the arts — I’m hoping the foundation will be able to fulfill her dream.”

Some of the foundation’s boardmembers have felt they’ve been left in the dark. They’ve issued numerous requests to Lindaman to hold meetings and to get to work but have received only silence in return. Even their entreaties to Wolf got nowhere. Utterly exasperated, and unwilling to sit idly by, three directors recently resigned: Towbes, Jordano, and Jurkowitz. None of them would speak directly to the Independent about their experience. Multiple attempts by the paper to reach Wolf for comment were unsuccessful.

Though both Lindaman and Schneider said that the New York Attorney General’s Office has had “complete oversight” of “all Foundation decisions,” an Attorney General spokesperson clarified that while the office oversees the formal registering and general regulation of charities, it has little to do with their individual operations.

Santa Barbara attorney Robert Ornstein, who specializes in legal and governance issues for nonprofits, is troubled by what he’s read about the Bellosguardo Foundation. “The well-being and stewardship of a 501(c)(3) sits squarely on the shoulders of the board of directors,” he said. “They have a legal responsibility to be awake and know what’s happening.

“The questions being raised are indisputably appropriate,” Ornstein went on. “A failure to respond flies in the face of what a 501(c)(3) is supposed to do, and that is to operate for the public benefit.” Other nonprofit leaders have expressed similar criticisms of the foundation’s lack of transparency. “Everything needs to be on the table,” said the director of a large Santa Barbara charity group. “Everything we do as a nonprofit has to be completely transparent. [Lindaman] needs to open up and be completely honest, or he’s not doing his job.”

So many red flags now fly over Bellosguardo that a Santa Barbara arts philanthropist recently hired a private investigator to dig into the foundation’s operations.

Shown the Door

John Douglas served as Bellosguardo’s resident manager for 35 years, living in a separate house on the east end of the estate and overseeing a small staff of gardeners and bookkeepers. His friends said he was intensely proud of his job, speaking often of the property’s magnificence and his commitment to preserving Clark’s legacy. He played an important role in the process to designate Bellosguardo a city landmark in 1994.

On November 19 last year, a month before ownership of the estate was transferred to the Bellosguardo Foundation, Douglas sent a letter to Lindaman and boardmembers reminding them that his and his colleagues’ employment would be terminated as a stipulation of the handoff. He implored the board to intervene. “I have been a loyal, diligent, and honorable employee,” he wrote. “There is not a building, system, tree, bush, or even blade of grass at Bellosguardo that has not been thoughtfully administered to under my supervision and tutelage during the last three decades.” Further, Douglas wrote, “Ms. Clark would be profoundly dismayed and saddened had she known that I, and the other employees at Bellosguardo, would face this sort of stress at a time when she was expecting her legacy to become even more firmly established.”

Douglas never received a response from Lindaman or anyone else, except Boardmember Towbes, who offered her sympathies. Towbes quit the board a short time later. Douglas declined the Independent’s requests for an interview. His friends say he remains heartbroken by the dismissal. Multiple sources claim Lindaman now entertains guests in Douglas’s former home.

White Elephant in the Room

While Douglas fought valiantly to keep Bellosguardo as intact as possible, the strains of time have taken their toll on the 1936 home. Warning signs on toilets connected to broken plumbing read “DO NOT FLUSH.” Cushions of a sofa covered in Louis XV upholstery have rotted. Traps and mothballs line rooms to keep rats and silverfish at bay. In total, the property is saddled with approximately $12 million in deferred maintenance.

The looming specter of a money pit forming on the property has prompted suggestions that the best way for the Bellosguardo Foundation to foster and promote the arts might be to sell the $85 million property and distribute the proceeds as grants to existing arts organizations. Schneider said she was always against that idea and made sure she chose a board that felt similarly. “My perspective was and remains that selling the property would have been a huge loss to the greater community, as once sold, it was gone forever,” she said.

Many within Santa Barbara’s arts and nonprofit communities, however, feel the current iteration of the board may not be capable of successfully ushering Bellosguardo into its next era. “You need someone in charge with a sense of entrepreneurship and a fiscal vision,” said the president of a prominent Santa Barbara foundation. “I just don’t see the necessary skill set on the board.” The CEO of an arts fund agreed. “The boardmembers who were willing and able to do the hard work have already left. I honestly don’t know what’s going to happen now.”

If there’s any immediate light on Bellosguardo’s horizon, it’s that the foundation is set to receive $4.5 million in cash as part of the final transfer of Clark’s assets. A public announcement is expected in the coming weeks. How that money will be spent remains an open question, and the clock is ticking. The monthly bills and upkeep of the 23-acre plot, including the workers’ salaries, cost approximately $40,000. And now that the nonprofit owns the land, it will need to start paying property taxes — one percent of its assessed value — until it secures an exemption. “They need to get this figured out sooner rather than later,” said one observer, who also worried that without Douglas and his long experience in preserving the property, the home will slip deeper into disrepair.

All is not lost, said another interested party directly involved in the nonprofit during its early days. But major changes in leadership are necessary if the Bellosguardo Foundation is to successfully carry out Clark’s will: “Something big needs to happen to help this organization recover from the sins of its past. And it needs to happen fast.”

Full Statement by Jeremy Lindaman, President, Bellosguardo Foundation

The Bellosguardo Foundation is pleased to announce that successful negotiations with the Internal Revenue Service have concluded and all tax issues related to Huguette Clark’s death have been resolved on favorable terms to the Foundation.

Since the Foundation’s formation, our objective has been a negotiated settlement with the IRS that allowed the preservation of Mrs. Clark’s Santa Barbara property. This has been accomplished. Further, the settlement, formally approved just weeks ago by the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, will leave the Foundation with assets in excess of the 2013 Probate Settlement best-case scenario.

The Santa Barbara community now has a Foundation with total assets appraised in the probate proceeding of more than $95 million. The 23-acre property, long a local mystery, can be preserved for public use.

The Joint Committee’s action follows the actual transfer of the Santa Barbara real estate to Foundation ownership, which occurred via court order on December 14, 2017. No announcement was made at that time because the order coincided with the Thomas Fire tragedy. The Foundation’s sincere sympathies are extended to all of the victims of the Thomas Incident.

As per the Probate Settlement, the New York Attorney General’s office has had oversight over all Foundation actions from its formation until October 2017. All members of the Foundation Board underwent thorough background checks by the Attorney General. The Foundation’s officers, employee and legal counsel were accordingly approved by the Attorney General’s office. The Foundation is grateful for their efforts and guidance working through this complicated process; without them this success would not have been possible.

The Foundation understands that the need to maintain confidentiality during the negotiating period resulted in some negative speculation and confusion in the community. Our limited public dialogue was out of concern that any announcements or comments could be misinterpreted by the IRS, jeopardizing negotiations.

The Foundation can now begin more publicly discussing the options for the property’s use. An appropriate press event will be conducted in the near future to provide more information.