The Bride of Jack the Ripper?

Is She Portrayed on Franceschi House?

Yet another book was published in the fall about the unsolved 1888 serial murders that gripped London, the country, and the world continuing to this day. There has been no shortage of suspects for the notorious crimes and a huge number of books, each with its own speculations.

They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper by Bruce Robinson is the latest investigation and adds a couple of twists. Robinson reinterprets the long-suspected London police incompetence as a cover-up for the killer’s connection to Freemasonry, a fraternal organization with widespread membership among government officials and the upper class. In addition author Robinson makes the case that a new suspect, Michael Maybrick, is really the infamous “Jack the Ripper.”

Coincidentally, Maybrick is a name on a medallion on Santa Barbara’s Franceschi House: Montarioso Medallion No. 58 is “Florence Maybrick, Prison Reformer.”

In July 1881, Alabama-born Florence Elizabeth Chandler gave up her American citizenship to marry wealthy British cotton broker James Maybrick. They lived in Battlecrease House in Liverpool, a mansion staffed with five servants and boasting ultramodern flush toilets. The new Mrs. Maybrick often hosted lavish parties; life was good but happiness fleeting.

By 1887 the cotton business was failing; finances were tight. James’s decade-old treatment for malaria — a common arsenic/strychnine remedy — had developed into an addiction. He had become an “arsenic eater.” His long-term mistress and several illegitimate children were exposed. Florence took her own lover (an unpardonable sin in Victorian England). James became even more mentally unstable and physically abusive toward his wife.

Michael Maybrick, the brother of James, arrived at Battlecrease House in early May 1889, summoned due to his brother’s failing health. He was an extremely prolific and influential musical composer, at the time having written more popular songs than Sir Alfred Sullivan (you know, as in “Gilbert and …”).

Michael confined Florence to the house and oversaw all James’s activities and treatments. Under Michael’s direction, James wrote a new will making Michael executor of the estate and guardian of their two children. And then James died on May 11, 1889.

Michael made a citizen’s arrest of Florence for the poisoning death of his brother and physically restrained her in the mansion for three days until the authorities officially arrested her. In the ensuing three months before her trial, James’s body was autopsied without any evidence of poison. He was buried, but the body was exhumed after three days and the heart, lungs and kidneys were sampled for analysis. Traces of arsenic were discovered in his stomach, consistent with James’s longstanding consumption.

Florence Maybrick’s murder trial lasted seven days, and the jury found her guilty after a half hour of deliberations. She was sentenced to die by hanging, the first American woman sentenced to death by a British court. There was no system of appeal.

The case aroused great American interest and outrage, due to the scant evidence, the brief trial, incompetent defense, and capital punishment. But Florence had forfeited her American citizenship to marry the Englishman so newly elected President Benjamin Harrison’s administration had no official standing to protest. Instead her supporters mounted an English-American campaign of hundreds of letters, including petitions from members of the British Parliament, judges, and barristers requesting leniency.

Four days before the scheduled execution, the British Home Secretary and Prime Minister advised Queen Victoria to commute the sentence. Their argument was that although Mrs. Maybrick may have intended to poison her husband, there was no evidence of that as the cause of his death. The Queen, still offended by Mrs. Maybrick’s adultery, grudgingly commuted the sentence to life imprisonment at hard labor.

Florence’s prison meals consisted of bread and gruel. The first nine months of her sentence were spent in solitary confinement. She was prohibited from speaking to other prisoners during exercise periods. She was required to make at least five men’s shirts each week.

Following the resentencing there began a long American campaign for a full pardon. An International Maybrick Association was formed. In 1891 a petition signed by the wives of all President Harrison’s cabinet members was directly delivered to Queen Victoria, an unheard-of affront to a British sovereign for the time. The American ambassador to the Court of St. James was Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham and Mary’s first child. He repeatedly delivered entreaties on Maybrick’s behalf during the four years of his office. It became clear the queen would be unmoved by continuing attempts, and the U.S. ceased official efforts in 1899.

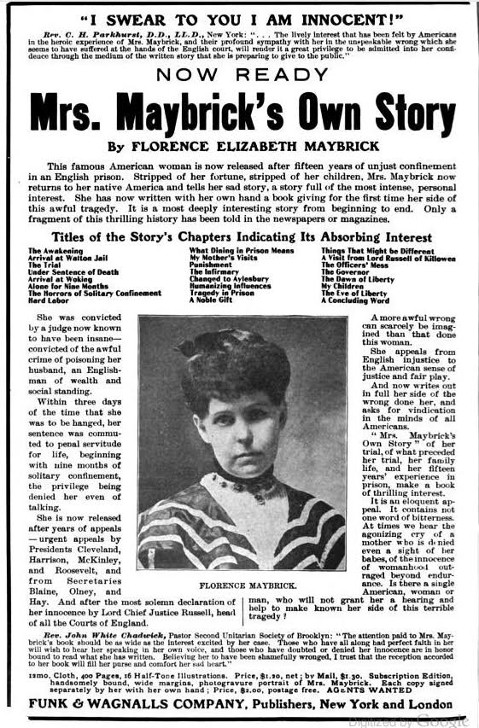

The Victorian era ended in 1901 with her death, whereupon Florence Maybrick’s sentence was reconsidered and fixed at 15 years, including time served. She was release from prison in 1904, returned to America, and reclaimed her citizenship.

She published a memoir, Mrs. Maybrick’s Own Story — My Lost Fifteen Years, in December that caught the attention of Alden Freeman, the owner of Franceschi House. He invited her to speak about her prison ordeal to a gathering at his New Jersey estate and encouraged her to launch a national lecture tour. She agreed.

Over the next four years she spoke in halls and houses packed with listeners who had read the newspaper accounts of her trial years before and had signed petitions for her release. It has been suggested that her activism and the international notoriety of her case contributed to the establishment of Britain’s Court of Criminal Appeal in 1907.

Both Florence Maybrick and Alden Freeman moved on, only to be reconnected in 1919. Maybrick, then penniless long after her lecture tour had ended, moved to rural Connecticut to start fresh using her maiden name, Chandler. Freeman learned of her situation and anonymously paid for her cottage to be built on a small piece of land and sent her $150 each month until 1931.

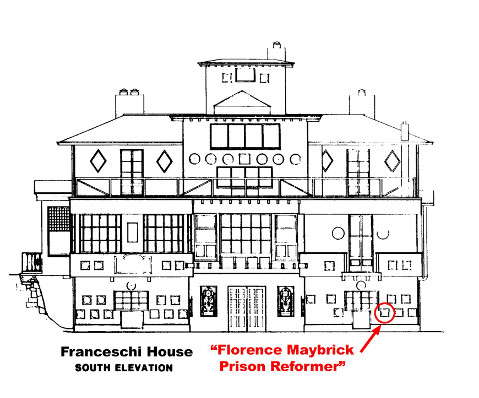

It was during this time that Freeman bought the land and house he would remodel and donate to our city. As part of the 1927 Franceschi House remodel into Freeman’s vision of a Mediterranean villa (to honor horticulturist Francesco Franceschi’s heritage), 85 sculptural elements, or medallions, were installed on the exterior, including one honoring Florence Maybrick as a prison reformer.

Freeman would later build his own home in Miami Beach with identical medallions. His Casa Casuarina was the final home of Gianni Versace and now is a boutique hotel and restaurant.

Was Florence Maybrick on our Franceschi House the sister-in-law of Jack the Ripper? That is the hypothesis of Bruce Robinson’s new book but each new account — there are dozens of books and thousands of “Ripperologists” worldwide — rests on the evidence and propositions of earlier work. The story, not necessarily the truth, is stranger still.

In 1992, 65 years after the Franceschi House Maybrick medallion was created, a handwritten diary and pocket watch were discovered that implicated James Maybrick — Florence’s husband — to be Jack. Robinson’s new book follows the Maybrick connection but posits the trail leads to Michael, not James. Either way, the story adds to the mystery surrounding the medallion Alden Freeman gave us on the south side of Franceschi House.

Visit the park and the house. See for yourself this interesting bit of history from 1920s Santa Barbara.

Rick Closson has collected hundreds of documents and images for the Pearl Chase Society in the course of his research on Franceschi House and Alden Freeman, the eccentric socialist who donated it to the City of Santa Barbara. A community campaign is underway to collect public ideas for Franceschi Park, as well as donations to rescue some form of the house.