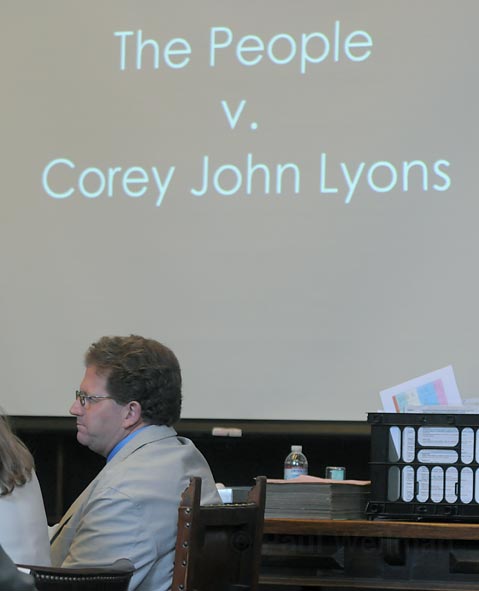

Hung Jury in Lyons Murder Trial

DA Already Makes Decision to Retry Case

For the second time in six months — this time because of a hung jury — Judge Brian Hill declared a mistrial in the double murder trial of Corey Lyons. Lyons is accused of shooting and killing his brother Daniel Lyons and Daniel’s life partner, Barbara Scharton, in their Mesa home early in the morning on May 5, 2009.

District Attorney Joyce Dudley said Thursday evening her office has already decided, after taking into consideration everything involved in retrying the case, to head back to trial. “Justice demands it be tried again,” she said. Prosecutor Gordon Auchincloss said earlier in the day he would meet with office administration and DA Joyce Dudley to analyze the case, the evidence, and feedback from the members of the jury.

In the second trial — after listening to 46 days’ worth of argument and testimony and seeing more than 400 pieces of evidence — the jury deliberated Lyons’s fate for approximately four days, beginning last Thursday afternoon and taking Saturday, Sunday, and Tuesday off. The four men and eight women emerged this Thursday morning, hopelessly deadlocked as to whether Corey Lyons did in fact kill his brother and Scharton. Afterward, jurors indicated that early on in their deliberation process, a group of seven believed Lyons was guilty, but by Thursday that number had dwindled to five. “I just couldn’t get past the reasonable doubt part of it,” explained one juror outside the courtroom.

While defense attorney Bob Sanger had no comment because the case is still pending, prosecutor Gordon Auchincloss said he was “obviously disappointed” by the result of the second trial. The first was interrupted more than a month into the trial in December 2010 when a witness, another Lyons brother, made a comment on the stand the judge deemed inappropriate and too prejudicial for the case to proceed.

The case was largely circumstantial for the prosecution, armed with no physical evidence proving Corey Lyons was in his brother’s home the morning the couple was brutally murdered, and without possession of the murder weapons themselves. Still, Auchincloss had some strong evidence on his side.

Last Thursday — with members of his family split, sitting on opposite sides of the courtroom — Corey Lyons heard the prosecution tell the jury he killed his brother out of “bitterness and rage” the same day they were supposed to sign a settlement agreement in a nasty lawsuit over the home Lyons constructed for his brother and Scharton, both attorneys from Fresno.

Lyons left a trail of evidence like breadcrumbs, Auchincloss told the jury in closing arguments last week. “In this case everything points toward guilt,” he said.

When officers arrived at his Goleta home not long after the murder, Lyons was not there and his wife didn’t know where he was. He also wasn’t found in a motor home across the street when authorities did a cursory search, but he later emerged from it.

There is evidence he made a call to his sister at 3:30 a.m. — an hour-and-a-half after the shootings — from the offices of a property management company he did maintenance work for; he also left a few belongings there. Some of those belongings, as well as his truck and his hands, were later found to have gunshot residue on them. Auchincloss said the residue was not from a construction gun or from brake dust as suggested by the defense.

While on the phone with his sister, according to her testimony, he told her it was “all over” at a time when no one yet knew about the murders. He added that what he was telling her was not a confession, but didn’t elaborate.

Corey Lyons was uniquely prepared to commit a crime early in the morning in the home, Auchincloss said. He knew the floor plan of the unusually laid out house, and owned several guns (though none recovered were weapons used in the murders).

Auchincloss also said a “whisper tape” between Lyons and his wife revealed the “unfolding of a phony alibi.” At first Lyons told his wife he was asleep in a motor home parked across the street when police came. But Millie Lyons, his wife, told him when police looked they didn’t find him. He told her he was using the bathroom.

Lyons also allegedly told several people he wanted to kill his brother. One witness testified during the trial about Lyons wanting to hire a hit man. “How could this possibly be a coincidence?” Auchincloss asked. He called it all a “trail of concealment that shows a consciousness of guilt.”

But Sanger, summoning a comparison to conspiracy theorists who connect the deaths of Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy, said that a few coincidences do not add up to proof beyond a reasonable doubt that his client is guilty.

Sanger, who called no witnesses in the defense’s case, said the police had “suspect bias” from the beginning when a neighbor talked to police and mentioned Lyons as a potential suspect. “From that point on, the case became one focused on Corey Lyons,” Sanger said. He suggested there were witnesses in the case who could’ve used a second look from law enforcement, but there was no follow-up.

Sanger went after the police, saying the record keeping in the case was terrible. He said Daniel Lyons was “not a nice guy” and that many people could be after he and Scharton.

Gunshot residue contamination, Sanger went on, could’ve come from any number of objects or locations — patrol cars, handcuffs, gun holsters, or the police station, which houses a firing range. And no one bagged Lyons’s hands to protect them before they were actually tested. “You have to look at the value of the evidence,” Sanger said. “You can’t be fooled by simply a whole lot of stuff.”

While there was evidence Lyons had a collection of guns, including a shotgun, it is not unusual for people to have gun collections, Sanger said, pointing out there was no firearms evidence linking Lyons to the homicide. “You can’t take evidence and make more out of it than what exists,” Sanger said.

Sanger also suggested the shootings couldn’t have been committed by one person. He used hypothetical bullet trajectory diagrams created by authorities to attempt to show there was no possible way one person could have committed the killings by themselves. He also pointed out that Daniel Lyons and Scharton were sleeping in separate rooms, and the timing of the shots neighbors heard (all in quick succession) couldn’t have allowed for one person to shoot the two, with multiple weapons, in separate rooms.

Add it all up, and Sanger’s arguments sufficiently raised doubt among several jurors.

Lyons will be back in court later this month.