Women Priests in S.B.

Part of a Worldwide Reform Movement within the Roman Catholic Church

Perhaps in some prior century, Suzanne Dunn and Jeannette Love might have been burned at the stake as heretics. These two gray-haired women — both quick to smile, soft-spoken, and light of spirit — are exactly what the Pope and Vatican insist can never be: ordained women priests. Yet three years ago, Dunn — a one-time parish administrator at St. Joseph’s in Carpinteria — was ordained in Santa Barbara by female bishop Dana Reynolds, who claims she can trace her own ordination back to St. Peter, the first Pope.

Since then, reverends Dunn and Love (Love was ordained one year later) have served as the spiritual center for the Church of the Beatitudes. The two have been saying Mass, giving out Communion, and tending to the sick for a small, slowly growing congregation throughout the South Coast. Dunn and Love are part of Roman Catholic Womenpriests — a worldwide group of clergy and laity seeking to promote gender equity and knock down the walls of hierarchy. The movement supports not just the ordination of women priests, but gay priests and married priests, as well. (Another Catholic “community of intention” — St. Anthony’s — has been presided over for the past two years by no less than four married priests.)

Late last Saturday evening, Dunn and Love co-celebrated Palm Sunday services in consecrated space they rent from the First Congregational Church in downtown Santa Barbara. The congregation of about 30, most of whom appeared to be in their sixties, were an enthusiastic group, singing together in vigorous, clear voices. As services go, it was decidedly unorthodox. To an exceptional degree, the laity took an active role in saying the Mass, going to the altar, for example, en masse to proclaim — along with the two priests — the Eucharistic prayer, the most sacred part of the Mass, when Catholics believe the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ.

Prayers were offered during the service by congregation members on behalf of former youth activist and Santa Barbara city councilmember Babatunde Folayemi (who died last week), recently deceased progressive hell-raiser Selma Rubin, United Farm Worker leader César Chávez (whose birthday it was), and for all the homeless struggling against unusually harsh winds and rain.

Eons have passed since church heretics were subjected to the agonizing purification of fire. Today, the Roman Catholic Church, via the administrative arm of the Vatican, deals with those who intentionally stray from church law simply by excommunicating them. And there’s no doubt that Dunn and Love defied the Vatican, still the most enduring, centralized, and powerful religious institution on the planet. In 2007, one year before Dunn’s ordination and two years before Love’s, the Vatican issued an unequivocal edict stating that any woman seeking ordination — and any bishop attempting to confer priestly powers upon a woman — would be excommunicated. Before that, Pope John Paul II had already ruled the ordination of women was categorically off-limits to theological debate. The church, he decreed, could not ordain women even if it wanted to; only baptized males were eligible. That’s because Jesus, in selecting his apostles, picked only men. This, the Pope insisted, was a fundamental core principle of faith that professed Catholics had to affirmatively embrace. Lest there be confusion, Cardinal Ratzinger — now Pope Benedict XVI — declared that John Paul II had invoked the papal powers of infallibility when issuing that decree. In underscoring that point two years ago, the Pope equated the offense of ordaining women with the sin of sexually abusive priests.

If Dunn is upset at being spiritually shunned, she doesn’t show it. “I do not accept excommunication,” she declared. In a separate interview, Love added, “We’re still part of the church. We didn’t leave the church; the church left us.” Neither is willing to accept the Vatican’s version of historical fact or scriptural interpretation. When Jesus reappeared after his crucifixion, they point out, he showed himself to two women, one of whom — Mary of Magdala (or Mary Magdalene) — was referred to in the Gospel according to John as “the apostle to the apostles.” They cite archeological records showing that during the first three centuries of the church’s existence, women were ordained as deacons, priests, and even bishops. While crucial, these are mere details in the broader challenge Dunn and Love pose. They question the core doctrine that the Holy Spirit calls on men and men only. This teaching is counter to their own life experience. Love said she received her “calling” while in 2nd grade; Dunn when she was 20. How can the church presume to dictate, they demanded, whom the Holy Spirit might call? “Why couldn’t the spirit call the women just like it called the men?” Love demanded. “It called me.” Dunn added, “What gets lost in this is the feminine dimension of God.”

Roman Catholic Womenpriests set out in earnest to expand the institutional church’s concept of the Divine in 2002 when seven European women — now dubbed the Danube Seven — were ordained by two male Roman Catholic bishops on a boat sailing down the Danube River. The Vatican condemned the action at the time as a “sectarian spectacle” and threatened swift reprisals against all participants. Today, Dunn estimates there are 100 “validly ordained” women priests and five women bishops worldwide, most residing in the United States. As a group, they’ve taken the famous adage by comedian Groucho Marx — “I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept people like me as a member” — and turned it upside down. Dunn and Love are refusing to be ejected by an organization that’s officially evicted them.

However one defines the “club” to which they belong, it’s clearly big. Roughly one-in-three U.S. citizens are baptized Catholic, making that faith the nation’s second largest after Protestantism. But roughly one-fourth of all baptized Catholics stop attending Mass, which statistically means that lapsed and disaffected Catholics could hypothetically rank as the nation’s next largest religion. By allowing women to become priests, Dunn and Love argue the church could alleviate the acute shortage of clerics now afflicting the United States. (Roughly one-third of all priests in the United States are foreign-born.)

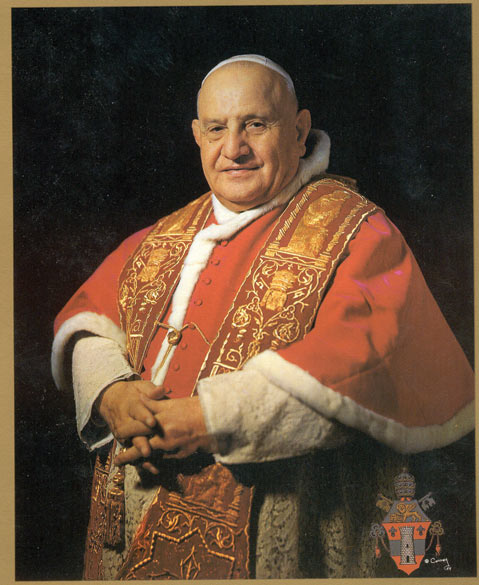

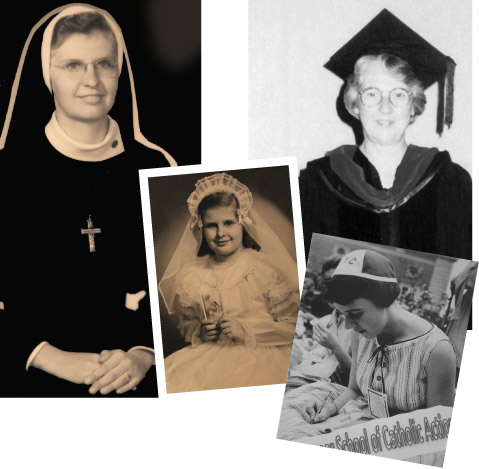

Dunn and Love grew up in devoutly Catholic households, Dunn in a small bucolic Vermont town and Love in the blue-collar city of Allentown, Pennsylvania. Both joined religious orders out of high school: Dunn became a Sister of Our Lady of the Victory Missionary, and Love a member of the Missionary Sisters of the Most Sacred Heart. Critically, both came of age theologically during the earth-shaking changes promulgated by Vatican II, under the direction of Pope John XXIII, nearly 50 years ago. That’s when a council of high-level clerics decided to instruct priests worldwide to abandon the Latin Mass, using instead the spoken language of their congregations. That’s also when the Vatican officially acknowledged the importance of the laity and parish councils. “For the first time, the church was saying, ‘The people are the church, not just the priests,’” said Dunn.

Supporters of Vatican II found their exhilaration short-lived. Since John XXIII’s death, the following Popes, they charged, have turned their backs on the reforms promised by Vatican II. “You can’t be empowered and then disempower yourself,” Dunn said. “It just doesn’t work.” She was particularly, profoundly upset that her gender should be seen as a barrier to her spiritual calling. Tom Heck, who plays guitar and sings during Church of the Beatitude services, echoed these concerns. “I’ll tell you something; when they’re dressed in liturgical garb, you can barely tell the difference between a man and a woman,” he said. “It’s so silly to be worried about gender when you’re talking about prayers of the heart.”

Dunn acknowledged she was tempted at times to join the Episcopal Church, where women priests have long been accepted. “I was angry,” she said. “But I didn’t want to act out of rebellion. Mostly, I just couldn’t leave the church of my youth. There was too much there.” Likewise, Love said she briefly affiliated with a Protestant congregation, but the pull exerted by her Catholic tradition proved too much.

Independently, both chose to join an experimental order, Sisters for Christian Community, which existed outside the direct command of any bishop. As Love recalled, the order provided a haven for the very liberal and very conservative without much in between. Because it operated by consensus, people holding polarized positions learned — by necessity — how to listen and get along.

Dunn moved to Santa Barbara in 1990 to finish a doctoral degree in clinical psychology; Love arrived in 1991 to take a position with Casa de Maria, where she provided spiritual instruction and led workshops in “centering prayer.” In 2005, Dunn was invited to attend a leadership workshop hosted by Fortune 500 management consultant Margaret Wheatley in response to the imminent collapse Wheatley foresaw of the world’s major political, financial, and religious institutions. “We were to be hospice workers for the dying, but midwives for the new,” Dunn said of the group — dubbed Women of the Willing Disturbance. To that end, Dunn started a Women of the Willing Disturbance gathering in 2003 in Carpinteria, where she lives. Every month in her mobile home park, about 12 women from various walks of life congregated. Dunn was one of them. (Another was Lynn Kienzel, wife of Santa Barbara Independent Type Consultant Bill Kienzel.)

When word of the Danube Seven broke, Dunn was initially dubious. “I didn’t take it too seriously,” she said. “My attitude was more like, ‘Good luck.’” But then in February 2006, Casa de Maria hosted a workshop about women and ordination, and the area chapter of Women of the Willing Disturbance actively participated. They were impressed by the speakers, who included PhDs from Harvard, and were moved by the possibility. Afterward, the Willing Disturbers met for dinner at Señor Frog’s, a Mexican restaurant in Carpinteria. Dunn was not there, having to work at St. Joseph’s. Everyone at dinner came to the exact same conclusion: Dunn should become a priest. Later that night, they went to her apartment to tell her so. “Are you sitting down?” they asked. “Oh my gosh, is this what a calling feels like?” she responded. “It certainly felt like one.”

Dunn already had a master’s in theology; to qualify, she needed to fill out a lengthy spiritual and personal autobiography to make sure her calling was not her ego talking. She was given a thorough psychological evaluation. And she had to complete 10 credits of coursework administered by the Roman Catholic Womenpriests. She had to tell her family back in Vermont. She was nervous how her relatives, devout Catholics, might respond. She told the priests she worked with at St. Joseph’s and Bishop Thomas Curry, as well. Her family, it turned out, took the news extremely well, flying out six relatives to attend her ordination. The reaction from St. Joseph’s was a mix of excitement and disapproval. And Bishop Curry, Dunn recalled, asked, “‘What is it you’re asking of me?’ I told him I was informing him, not asking. And he said, ‘Well, let’s see what happens.’” (Phone calls and emails to Curry had not been returned as of press time.)

What happened was this: On September 27, 2008, Dunn was ordained as a priest by Dana Reynolds — herself ordained by one of the Danube Seven and the first woman to be made a bishop in the United States. In the intervening three years, Dunn — along with Love — has found herself consumed with the day-to-day details of being a priest. It has not grown stale. “I wake up amazed sometimes,” she said. It’s not something I could have ever dreamed of.” In the meantime, their Church of the Beatitudes has grown slowly, ripening into an enthusiastic niche community favored by liberal, social-justice–minded Catholics who find themselves increasingly at odds with their Pope. Worldwide, there are maybe 100 ordained Roman Catholic Womenpriests, about 70 in the United States. While the Santa Barbara Community is predominantly older — no families, no baptisms, and only a few weddings — there are a handful of thirty-somethings in attendance. In San Diego, the community is reportedly much bigger and has succeeded in attracting some younger families. Up in the Seattle area, the church is experiencing the most rapid growth.

This week, Dunn and Love are hard at work preparing for this week’s Easter celebration, an ancient series of ritual ceremonies that begins this Thursday. Given the competing demands for space, the Church of the Beatitudes will hold its Easter-week events at Casa de Maria rather than the First Congregational Church. In the meantime, the Pope and the Vatican betray no indication their position is softening. For Dunn and Love, that’s unfortunate but to be expected. Certainly, they’re not about to back down either. “We waited and waited and waited for the Church to invite us in,” explained Dunn. “Now we’re saying, ‘Here we are.’”

4•1•1

Special Easter-week services for Church of the Beatitudes will be held at the chapel of Casa de Maria Retreat Center (800 El Bosque Rd., Montecito) at 7:30 p.m. on Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday; and at 9 a.m. on Easter Sunday. Call 969-5031 or visit beatitudes-sb.org