Arturo Tello’s Mishopshno, Whitney Brooks Abbott’s Harvest, and Tom Henderson’s Slices of Life.

At the Easton Gallery. Shows through December 2.

Fifty years ago in this town, Aldous Huxley gave a series of incisive, prophetic lectures, the third of which was entitled “More Nature in Art.” In it, the brilliant social satirist and late convert to Eastern and psychedelic mysticism argued that painting had become “an escape from the concrete : into descriptions : of our technological civilization.” What was needed, he claimed, was “something profoundly religious in landscape painting : to explore and express the layer of the unconscious which is beyond the personal unconscious.”

Twenty years ago, Santa Barbara’s Oak Group painters began just such an exploration of nature, with the idea that the results might help preserve the environment itself. Among the Oak Group’s founders was Arturo Tello, one of three artists whose work is currently featured at the Easton Gallery. Tello has recently been collaborating on a book of illustrated haiku. Perhaps for that reason, many of his paintings, split between trees and sullen scapes, bear abstract titles. A view of dark mountains is called “Passion”; a stand of eucalyptus gets the title “Permanence.” At times, the themes seem arbitrary. “Legacy,” tall trees standing near a cliff, looks pretty impermanent until you read the title. Other works, like “Bliss”-a burst of blooming bougainvillea-and “Afterglow,” obviously mirror the idea.

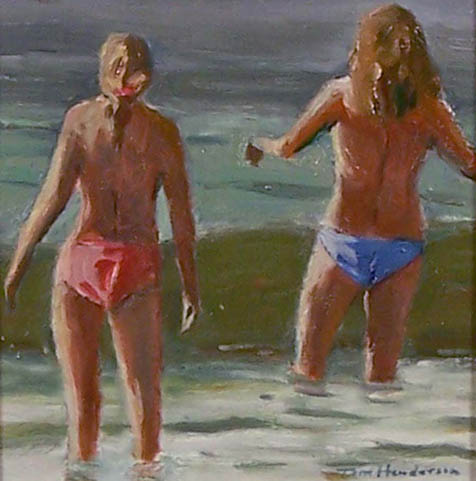

Tom Henderson is not a member of the Oak Group, though his watercolors are vivid records of our sun-baked environment. Here he exhibits new works, including some surprises in oil, with deft, spontaneous brushstrokes. The works that succeed best are those of more kinetic subjects, including two bathers (“Heat Wave”), and boats huddled in a harbor (“Morning Fog Monterey”). Henderson’s connection to the unconscious is light and lightness: a human world on the edge of the moving seas.

The most affecting of these natural explorations, though, are the paintings of Whitney Brooks Abbott, whose most compelling work pushes landscape toward design. Consider “Mustard Shed on 33,” where brushstrokes suggest shaping forces like Taoist DNA. “Thisbe’s Syrah” and “Deciduous” reach into reflective moments. Other paintings play on the dark side: “March Haze” evokes last summer’s skies after fires, poisoned and malevolent. Most landscapists find idealization too deep a temptation, but at her best Abbott plays outside all that, making the leap to a deeper layer of the unconscious.