Talking Dirty with Clean Water Czar

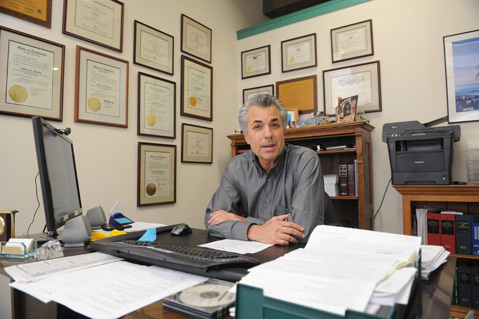

Jeff Young Examines Ag Runoff, Urban Soup, and Diablo Canyon Heat

Jeff Young has the dubious distinction of having made Julia Child sick to her stomach. For what it’s worth, he wound up getting sick, too. That was about 20 years ago when Young was a budding oyster farmer then celebrating his grand opening with an extravagant chow down at the Wine Cask. Within weeks, environmental health officials would shut Young down, citing unacceptably high levels of fecal coliform in tissue samples taken from his oysters.

Young — who holds a degree in mariculture — was not inclined to go quietly into anybody’s good night. He would soon discover his oyster barge located off Hendry’s Beach lay in the crossfire of two sewage effluent plumes — one from the Goleta Sanitary District and the other from the City of Santa Barbara’s sewage treatment plant. Neither, he would contend in subsequent lawsuits, had been sufficiently treated. As a result, he claimed, his business was destroyed. Santa Barbara quickly made adjustments. Goleta, by contrast, fought him tooth and nail.

Along the way, Young found himself pursuing a whole new dream. Forced to give up oyster farming, he got a law degree. And he became an anti-water-pollution champion. For years, he teamed up with Hillary Hauser to form Heal the Ocean’s one-two punch. Where Hauser, noisy and passionate, played the role of the iron fist, Young — more reserved and studious — emerged as the velvet glove. By calling into question whether Santa Barbara’s beaches were as pristine as they seemed, Hauser and Young made creek and ocean pollution an issue that neither politicians nor bureaucrats could safely ignore.

Hauser would lead the charge against leaky beachfront septic systems, pressuring unwilling property owners to hook up — at the time at significant cost — to sewage systems. Young would be appointed to the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, a relatively obscure state agency with significant regulatory and enforcement authority to enforce state and federal clean water rules. As an activist, Young chaffed at the board’s lack of regulatory initiative and enforcement zeal. But late last year, he was appointed by Governor Jerry Brown to his third four-year term. And for much of his tenure on the board, Young — distinguished by a calm, open, even-handed style — served as chair.

As such, he presided over some intensely contentious issues. When the board ordered the small community of Los Osos to dispatch its human waste into a sewage system — as opposed to septic — the blowback was intense, personal, and at times, blood-curdling. The board received similar reactions when it notified the 2,500 farming operations in the Central Coast district that they — for the first time — could no longer allow their agricultural runoff to flow unregulated into nearby creeks. Ag wastes were not just polluting the ocean, Young noted, but contaminating groundwater basins upon which residents relied for drinking water. Young expected farming interests to recoil, but he was more than a little surprised in the attending din that not one elected official saw fit to testify on behalf of clean water.

Young is now one of two Santa Barbarans now serving on the Central Coast board; the other is Santa Barbara City Planning Commissioner Michael Jordan. Young recently took time to talk with Santa Barbara Independent reporter Nick Welsh about water quality issues affecting the South Coast. The following is an edited version of that exchange.

When you look at this area, what are the big red-light issues when it comes to water quality? There are two. What we have here is irrigated agriculture. And then municipal areas, the urbanized areas. Those two land-use practices are the predominant impacts to water quality in our region.

Urban stormwater runoff — how bad is that? Depending on where you’re looking, it’s bad enough that we have pollutants in some of our surface waters — creeks, rivers, streams — that are impacted enough they qualify for a federal Clean Water Act listing.

What areas around here? We have them all. There are 56 unique water body segments in Santa Barbara County that are on the list. It could be a stretch of a creek or river with elevated levels. You could have for a given river, multiple unique stretches that may have violations.

So what are the typical issues? What we have for urban pollutants is the oil and grease in gas and hydrocarbons that come off of our vehicles. That gets washed into surface waters. We have heavy metals from brake linings that come off cars that get into surface waters. We also get bacteria; people walk their dogs. Sometimes we have breaks in storm-water lines where sewage lines are discharging. The City of Santa Barbara was able to detect and finally correct a leak it had from a sewage line that was crossing over a storm-water line underground, getting a discharge into Mission Creek during the dry season. It looked like water, but it was laden with bacteria. It took awhile for them to trace. We do have breaks that we’re just not aware of and that can end up in the urban soup.

As you look into the urban soup in our area, how significant is this? It depends who you ask. Ask Andy Caldwell, and he’ll say, “Who gives a shit?” He’ll say, “I can see the water.” I’m being facetious, but he came to the water board and complained that we were even thinking about issuing any limits for the Santa Maria River. He said, “I drive over that bridge every day. There’s no water in that river. What are you guys trying to do? Get a life.” But it’s a concern. The urban soup impacts receiving waters. It impacts that natural assemblage of invertebrates and fish that we would normally have.

How well do we understand this? One thing we don’t have a lot of data on is the ecology of a lot of our streams. The water board is slowly studying this and getting bio assessments of the assemblages we have. We’ve been better lately in getting water quality data. For many years we only had data the discharges gave us. So we were limited. In the last 10 years the Central Coast [Water Quality Control Board] has had its own ambient water quality monitoring, and we’ve had more data than any other region in the state and more than the state board does. We divided the Central Coast into three sections, and we have staff who just go out and take ambient water quality samples so we have our pulse on what’s going on.

So how are we doing? We’re holding steady. We haven’t improved anything in the urban context at all because we are only now implementing our storm-water permits. These storm-water permits that have been issued locally have only been in existence for three or four years. We’re making progress, but it’s not like it’s going to happen overnight.

How do you treat storm water so it’s not an issue? The best way is using low-impact development standards. What we want is storm water to not be channelized and sent right out into the ocean. We want it to infiltrate into the soil. So that means swales. Permeable pavers. Permeable concrete. Permeable parking lots. Even streets. Capturing water off of roofs, creating rain gardens. We want to allow water to get into soil and let the soil purify it and recharge the groundwater. Two big things. Really critical. Now because of the big drought, this stuff is really critical.

How hard is this to do? It’s easy. It’s easy. But with some bureaucrats, there’s the mind-set, “How much is this going to cost, and why do I have to spend this much now?” What they don’t appreciate is yes, there’s a higher initial cost, but you don’t have the maintenance problems down the line. You allow processes that would take place naturally in the ground. That’s a huge benefit.

Now that we’re looking down the barrel of a drought, people are talking about the desalination plant more. Is this something your agency would be concerned about, and what’s your issue of jurisdiction? Yes. They’d be discharging brine.

Adding more salt to salt water, is that a problem? Too much of something can be bad, even if it’s a good thing, like too much carbon dioxide, if you know what I mean. If you have a very salty discharge, the concern would be impact on the receiving waters. Because it’s super saline, that’s not natural to the marine environment. So the question would be how long is it going to take to blend in and dissipate, and how will it affect — if at all — the receiving end biota.

You raise questions, but do we know anything? My experience is limited. In Monterey, there’s a lot of talk. They have a water shortage, and they’re pushing for a desal plant up there. They’re very water short. Nothing has come before the board yet. The concerns are similar to Diablo Canyon: You’re drawing in sea water. Depending on the intake, the volume of water and screening mechanism, the question is what are you going to be killing? You’ll be killing some fish, killing some phytoplankton, and how do you avoid that? There are some designs I’ve seen that minimize the impingement and entrainment. Impingement of larger objects and entrainment of eggs and phytoplankton. There’s going to be an impact, but is it significant? Is it something we can live with?

I hear the issue that Diablo Canyon is heating up the marine environment is a big one with your board. That hasn’t come back to us, but I hear it will soon. We were looking at it, but the state board took over. Now I hear they’re getting ready to drop it back in our laps. What we said back then was that the heat impacts are severe. We were getting species from San Diego making their way up the coast for the heated effluent created by Diablo. These would be species that came up here for the warm summer water naturally but that would then head back. Now we found some got all the way up there and are living up there year-round . The discharge area was changing the environment. I forget how big an area. It wasn’t huge. But it has different species growing in it. New migration patterns. We told Diablo Canyon, “You’re going to have to mitigate that.”

The question was, what’s the right mitigation? Some groups wanted us to shut it down. But that wouldn’t have been too popular with the governor’s office, no matter who was governor. What are you going to do — take this power offline over this? So what we proposed was having them provide more habitat for the invertebrates and the fish. That’s what we were trying to do when we got sidetracked by the state board.

When you were put out of business as an oyster farmer, you sued the Goleta sewage district. Did any changes in practice come from that? The EPA immediately ordered Goleta to disinfect its effluent and to build permanent disinfectant facilities, which they didn’t have. It ordered Goleta to do a field study to determine if the bacteria could come down the coast and how far.

Did Goleta put up a fight? They put up a great fight. They actually went to Congress. Their old directors wanted to get an exemption so they wouldn’t have to build a full secondary treatment process. Goleta at the time was discharging at a very poor level of primary treatment. I mean, it was bad. If you looked at their effluent in a jar, it was grey. Santa Barbara’s would have been clear. It would have been full of bacteria, but it would be clear. Goleta put up a fight. They didn’t want to go to comply.

Wasn’t their argument that the solution to pollution is dilution? That was the argument. It was developed back in the 1950s by sanitary engineers from Los Angeles and Southern California. The idea was the ocean is a big place. Just dump it out there. No one’s going to see it again. The other argument was that we were encouraging phytoplankton to grow — we’re fertilizing the grass so that the grazing fish have more to eat. They were looking for reasons not to do it, including costs.

So you go from a guy who studies mariculture, starts your oyster farm, gets Julia Child sick, gets put out of business, and becomes a clean water crusader. What was your perception of the board at that time? At that time, I felt it should be doing more. It should be coming in faster with a heavier hand to get these things fixed. And it shouldn’t be letting them happen. I also saw that this agency had a lot of power over water policy. It has a lot of influence.

So do you go in the water anymore? Not as much as I used to, but yes.