Jacob Snyder 1980-2008

On Saturday, April 5, at 10:20 a.m., northbound Amtrak 799 struck and killed a homeless pedestrian near the Milpas Street crossing. That homeless pedestrian was my 28-year-old son, Jacob Snyder. What happened? Rewind 10 years.

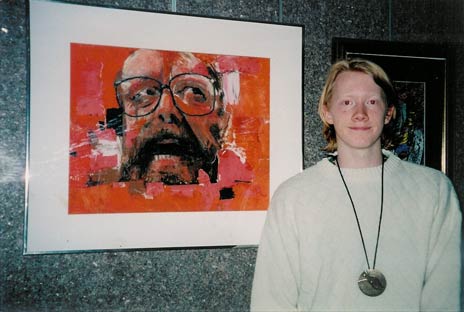

Jake is 18 years old. He debuted as a professional bass player one year earlier. Jake’s portrait of his art teacher, “Orange Man,” has won the top award at the Ohio Governor’s Show. I take him and his then girlfriend, Bianca (who is now finishing a graduate degree at Yale), to a holiday party at the home of my employer, Ohio State University’s president E. Gordon Gee. Even though his home is full of important people eager for his attention, President Gee focuses on Jake and Bianca as if they were the only people in the room, even abandoning the other guests altogether to take Jake and Bianca upstairs to show them his personal collection of Calders and Mir³s. I am so grateful for this special treatment of my talented son. What happened?

Not only was Jake extraordinarily talented artistically and musically, he was also blessed with a keenly sensitive conscience, a quirky sense of humor, and a gentle spirit. My husband remembers that after Jake returned from a trip to Haiti that same year, he told us of meeting some Haitian children who had caught a bird. They had tied a string around its leg and were trying to sell it to passersby along the side of a road. Jake bought it from them so he could set the poor little thing free. He was so sweet and compassionate. What happened? Rewind 10 more years.

Jake is about eight years old. On a spring afternoon, he is out of school early, and we are walking along High Street in Columbus, returning to my office on the university campus. Outside a storefront, a disheveled man sits, asking for change. Jake is dumbfounded and even outraged about why the man is there. Why doesn’t he have a home? Doesn’t anyone care about him? How did this happen? I answer his questions as best I can and tell him he shouldn’t worry about it. It isn’t his problem. It is the man’s problem, and it would never happen to Jake. He is not satisfied. He replies, with tears in his eyes, “But Mom! It’s like someone took a precious ruby, and just threw it out in the gutter.” I am amazed by the force of his compassion, and humbled by my lack of same. Fast forward 20 years.

More recently, and especially the past three years, Jake’s life was marred by confusion, anger, and frustration as he was engaged in what felt like a death struggle for his heart and mind.

After graduating from Ohio State, it seemed to me that Jake became possessed by a sense of entitlement, feeling that he shouldn’t have to do anything he didn’t particularly feel like doing. He often expressed a belief that life should be easy. And he began to embrace a conviction that a person’s moral code is entirely subjective and so just about any conduct is permissible. He abused alcohol and drugs. Jack Kerouac was his new hero. His world view seemed distorted, and I lacked the sophistication to help him adjust it. We tried every way we could think of to help him. We tried patience, we tried psychotherapy. We tried to encourage medication. We tried tough love and soft love. We tried recovery programs. We tried job counseling. We tried kicking him out of our home. We tried taking him back. We felt like we were throwing him every kind of lifeline we could think of and he simply refused to grab on. Because he had also suggested his problem was geographical, and because of his disruptive behavior at home, we put him on a bus to Santa Barbara.

That is what happened. That is how Jake became part of the “homeless problem.” But that “homeless problem” is made up of individual people. Each of their stories, like Jake’s, is unique and special, but all are stories about people who, for very different reasons, are unwilling or unable to fit in with the rest of society. What to do? I don’t know how to solve the “homeless problem.” I couldn’t even solve one person’s problem. But I believe in continuing to throw them lifelines-even something small that simply conveys the message, “Hey, you’re still a person, worthy of saving.”

Kind people in Santa Barbara kept throwing lifelines to Jake. People like James Hernandez, who found Jake’s luggage in a parking lot and stored it. Not only did he call our home to let us know he would keep it safe for as long as needed, he called back a week later to check if we’d heard anything from Jake. Like Officer Rick Alvarado, who found Jake sleeping behind a dumpster, called us, and took him to pick up his lost luggage. Like Rolf Geyling, who gave Jake a cup of coffee and a doughnut because he looked hungry as he was sitting outside the Rescue Mission. And like “Stretch,” a resident at the mission who gave Jake clean socks, a blanket, and tried to make him laugh.

Why bother with these stubborn screw-ups? You never know when a person will finally decide, yes, I’m ready to get off the street. I’m ready to become the person God intended me to be.

Even my husband and I did not give up throwing lifelines. Jake knew we had offered to send him to a symposium for bass players outside Nashville in September. And we encouraged him to apply for the resident program at the Santa Barbara Rescue Mission. I sent him an application. But he would not grab the lifeline. And then there was the train accident.

Our hearts are broken over the loss of our precious Jake, who ended up as a homeless guy in Santa Barbara. Fortunately, we have many photos and memories of the good times with him, when he was whole and well and gut-bustingly funny. And in a way, he is now home more than any of us. Because when someone threw him the Big Lifeline, he grabbed onto that one. In a sense, we’re all homeless people on our way home. So let’s be kind to those who journey along with us. Please keep throwing lifelines.