Indy Reporter Does Sleep Study

The Night Watchmen

My roommate snores. Until a couple weeks ago, I discounted it as an annoyance and occasional-okay, often-interruption of sleep. Now, after having participated in a polysomnogram, a sleep study if you will, I think there may be more to his nighttime noisemaking; I think he has obstructive sleep apnea.

When word went around the office that a subject was needed for a sleep study, I pounced on the opportunity. When the day came, I packed my overnight bag, grabbed my favorite pillow, and headed to the Arete Sleep Health Sleep Lab, where I met Mansoor Hussain, the lab supervisor for the three Arete sleep labs on the South Coast. The newly renovated Arete in Santa Barbara used to be known as the Sleep Disorder Center of Santa Barbara and sees three to five patients every day of the week. I didn’t think I had any sleep problems going in, but I was still a little nervous to discover what the study might find.

The sleep lab resembles any doctor’s office-a waiting room, thousands of files stacked behind the receptionist, and four or five private rooms tucked into the corners of the hall. Unlike other doctor’s offices, however, the treatment rooms at Arete don’t have uncomfortable plastic table beds draped with butcher paper, but rather cozy-looking double beds, a nightstand, and a television.

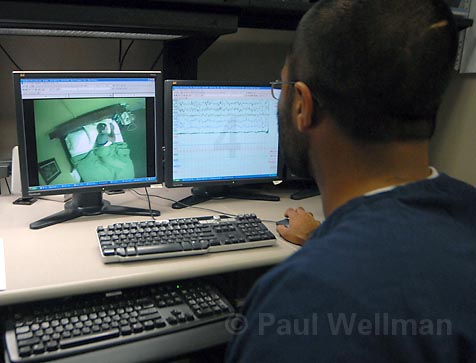

After I changed into my sleepwear, Hussain brought me to the information station, a room with several televisions and computers where patients are monitored by technicians throughout the night. There I got geared up for the evening, with Hussain attaching various wires and sensors to my face, head, shoulders, and legs, as well as my chest and abdomen. He also placed small little tubes in my nose to register my breathing patterns. It sounds like it might be uncomfortable, and it did take some time to get used to having wires come out of my head, but overall it wasn’t too bad. Hussain and I headed back to my room, which was also outfitted with a couple cameras so the staff could watch me twist and turn through the night. Hussain left me to watch a little television before drifting off to sleep.

While I wasn’t completely comfortable with my surroundings, and I went to bed a little earlier than normal, I feel asleep readily enough and awoke feeling like I’d slept pretty much as I normally do, which, according to the study, isn’t particularly abnormal. The results did enlighten me to some of my nighttime quirks. One of the most interesting pieces of information I got from the study is I sleep on my back. I always thought I slept on my sides, never on my back. But for more than two hours that Friday night, I slept on my back and when I did, my apnea level increased to 7.8 events per hour.

Out of Breath

Apnea events lasting longer than 10 seconds are considered significant, but many usually last from 20 to 30 seconds and some can last longer than a minute. The apnea episode usually ends when the patient wakes up because they can’t breathe, and the body’s “arousal” response allows the person’s airway to reopen. Even though the body wakes up, the person usually doesn’t remember it, which is one reason people don’t realize they even have sleep apnea. Like my roommate, people have little to no idea there may be a problem unless someone tells them. If the apnea is serious enough, it doesn’t matter if a person sleeps for one hour or 12, they won’t feel well-rested when they wake up.

My longest bout of apnea lasted 19 seconds. Scary, right? Hold your breath and count to 19 seconds and tell me this isn’t a scary fact. I didn’t know how to react to the fact that at points during my sleep that night I was not breathing. Luckily, the events were few and far between-only 3.1 per hour-not nearly enough to be considered abnormal.

What is abnormal, Dr. Charles Curatalo-a registered Santa Barbara sleep doctor-told me, is when people have breathing pauses between 30 and 100 times per hour for up to a minute. This, as one might imagine, leads to almost no deep sleep. While doctors still haven’t figured out why we sleep, there’s no question that we need it. We spend one-third of our lives under the covers, and studies have shown sleep is important for the state of the brain as well as the functionality of our immune systems, among other things.

Some doctors believe the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep, when the brain is in a very active state, is used for memory consolidation. But not getting sleep clearly causes impairment, Curatalo said. Aggravated headaches in the morning are common in those who can’t sleep, and a person’s memory, concentration, and mood are all affected. According to some studies, people with sleep apnea are twice as likely to get into a traffic accident. There is almost certainly a direct correlation between a person’s weight and having sleep apnea. Chances are greatly increased that a person with a body mass index higher than 30 (normal would be between 18 and 25) has sleep apnea. A large neck often will weigh on the throat to the point where the person’s breathing tract is blocked.

Besides sleep apnea, many other sleep disorders can be spotted during a sleep study, including Restless Legs Syndrome, narcolepsy, periodic limb movement disorder, and parasomnias, which include sleep walking and talking, teeth grinding, night terrors, and REM sleep behavior disorder.

Eyes Wide Shut

There are 79 kinds of sleep disorders affecting more than 70 million Americans-many of whom don’t even know they have a problem. Between 80 and 90 percent of people with obstructive sleep apnea are undiagnosed; the average patient goes seven years before being diagnosed.

The seriousness of sleep apnea has gone from the academic world to the real world, explained Jeff Barr, a South Coast territory manager with Arete. As technology has picked up in the last 30 years, so has the medical community’s awareness of just how big a problem sleep apnea can be. “Nobody took it seriously until there was a way to clearly replicate a night’s sleep and document the disorders,” Barr said. Another problem, said another Arete South Coast territory manager, Summer Battle, is getting the word out to doctors to question their patients regarding their sleep habits. According to a 2002 article in American Family Physician by three doctors in Israel, when physicians ask patients about snoring, excessive sleepiness during the day, and reports of apneic events, the number of diagnosed and treated cases increases eightfold. “If you stopped breathing during the day you would run to your doctor,” said Battle. “But when people are sleeping they don’t know.”

So how is apnea, the most prevalent of sleep disorders, treated? Before I hit the hay for the night, Hussain fit me for a CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) machine, a little mask that covered my nose and forced my throat open, leaving a way for airflow to move freely. If Hussain or his technician had diagnosed any potential sleep apnea that night after two hours, they would’ve hooked me up with the machine. After the sleep study, people are diagnosed by a doctor as to whether they could benefit from CPAP therapy, which, along with the sleep study, is often covered by insurance. There are many shapes and sizes to a CPAP, which now are made to be nearly silent and can fit into a travel bag. While it takes some getting used to, the CPAP can change the way a person sleeps. Many apnea sufferers haven’t experienced a good night’s sleep in years, but after one night using the CPAP they feel more rested than they have in a long time.

Getting treated for sleep apnea can also help people lose weight. Sleep apnea can alter certain hunger-inducing hormones, tricking them into believing the body is hungry. The body doesn’t tell a person with sleep apnea that they’re full, and they end up eating more, leading to weight gain. Once the apnea is treated, the artificial need to eat is eliminated. So, getting treated for sleep apnea doesn’t just mean you’ll get a good night’s sleep, but also that you can expect to see a reduction in blood pressure and a lessened risk of stroke and heart disease.

However, according to those at Arete, 50 percent of the national apnea sufferers can’t get used to the CPAP and throw it into the closet. (At Arete, initial meetings with respiratory therapists are arranged along with follow-up meetings, and compliance by Arete patients is at about 90 percent.)

I met with Curatalo-who has more than 16 years’ experience treating sleep disorders-the week after my sleep study, and I was informed by the good doctor that I have no clinical sleep disorder. (I did, however, learn lots of interesting tidbits from my information-packed report. For instance, I only spent 10.7 percent of my time in bed in REM stage sleep, while generally a person would spend 20-25 percent in the dream state.)

But I was armed with all sorts of information to take home to my roommate, as well as the idea of how the treatment of sleep apnea can make a world of difference. “You really are changing the life of the patient,” Hussain said. Now if I could only convince my roommate to let Arete help him, maybe we both could get a good night’s sleep for once.