Bailout Blues at 2013 Economic Summit

Economy Showing Signs of Growth but at the Cost of Moral Hazard?

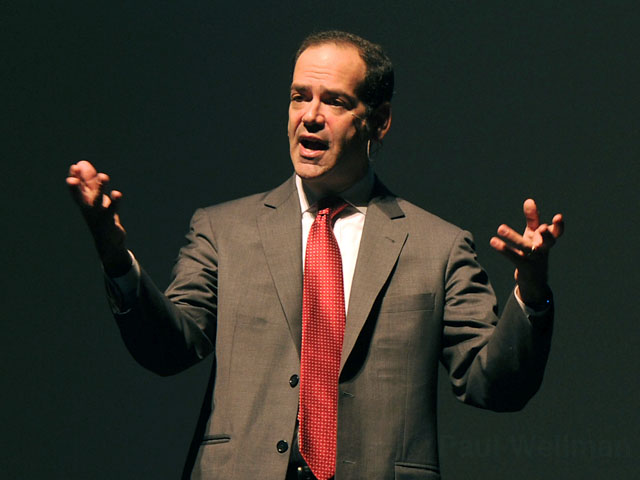

“Too big to fail in 2008 has become too big to jail in 2013,” said Neil Barofsky, former inspector general of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), this Thursday, remarking that nobody from the financial sector has been prosecuted for actions that led to the Wall Street meltdown of 2008 because the Department of Justice feared such enforcement would upset the global banking industry.

The ostensible headliner at this year’s Santa Barbara County Economic Summit held at the Granada Theatre, Barofsky was actually the first speaker to take the stage, and he did so with a no-holds-barred takedown of what he described as an anemic banking regulation system. By speaking first, Barofsky set the tone of the event where he was followed by NYU economics professor Thomas Cooley and Douglas Elliott, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. In a brief round table discussion between them and UCSB Economic Forecast Project director Peter Rupert, the conversation focused on the social cost of regulation as much as it did on the economic cost.

Barofsky’s front-row view of the Treasury Department did not leave him impressed, nor did it leave them too pleased with their moralizing auditor. When Barofsky accused the department of opacity, Timothy Geithner, he said, yelled at him for “daring to suggest that he was anything but the single most effing transparent Treasury Secretary in the nation’s history,” and, added Barofsky, “he didn’t use the word ‘eff.’

Geithner also didn’t follow through on the TARP’s original mission, which was to buy up bad securities. Instead he infused banks — including those guilty of causing “the financial equivalent of 9/11,” in the words of one of Barofsky’s former bosses — with cold hard cash. Officers kept their obscene bonuses, homeowners never got the help they were promised, and the the government “doubled down” on a perverse financial system that incentivizes risky behavior, Barofsky said.

The regulatory system, he went on, needs just as much reform as the banks. That’s because regulators often come from the industry and think like bankers. And they accrue personal success by not making waves. When Barofsky went out for a drink with Herb Allison, the Treasury official who headed TARP, he claimed Allison told him that he could recuperate his chances for a plum political appointment. “All you need to do is change your tone, be a little more upbeat,” Barofsky said Allison told him.

Barofsky, who once prosecuted drug cartels, thought that he was being threatened with the tactics Pablo Escobar would use to corrupt government officials — by offering a giant bag of gold or a bullet in the head. He has since decided that Allison, who understood how the “go along to get along” culture of Washington works, was simply offering advice. If anything is to change, “aggressive regulation” needs to be incentivized, said Barofsky, who has written a book, Bailout, about his experience.

While Barofsky ended his talk by saying we could be on the precipice of another financial collapse, professor Thomas Cooley said his talk would be even more pessimistic. Cooley opined that the European banking system is four times as risky as the U.S. system. In contrasting the two systems, he said the U.S. benefits from a common fiscal policy, financial burden-sharing, labor market mobility, and uniform deposit insurance.

As an aside, he did point out that the most risk-laden institutions are those that benefited most from the bailouts: Bank of America, J.P. Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Metlife, Prudential Financial, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs. Forcing banks to raise capital would be a smart regulatory means to avoiding future crises, he said.

Douglas Elliott of the Brookings Institution was both more bullish on the economy and less strident on the need for regulation. “I hear too many people … speak as if we have accomplished nothing because we have not accomplished everything,” he said, adding that the Dodd-Frank Act provided the basic protections necessary for the banking sector (although he “hates” the Volcker Rule). “Much of what happened after the crisis,” he said “would have happened even if regulators stayed home.”

Furthermore, he said “too big to fail” was, at most, 10 percent of the problem, pointing out that without huge banks there would still have been bad mortgages, high risk, and negligent ratings agencies. And he disagreed with Elliott about the imminent dangers of a Eurozone collapse. “I’m not trying to be a Pollyanna here, but I don’t think they’re going to implode,” he said.

Back here in Santa Barbara, Peter Rupert said, things are getting better, slowly. There has been zero job growth in government, the county’s largest sector. But overall, employment is growing and home sales are up. Income, however, lags inflation.

Long-term, he said he remains ruddy as the GDP in the region has grown steadily since 1929 despite blips during the Great Depression and World War II. Pointing at a graph of the logarithm for GDP, he said, “Democrats, Republicans, whatever, it grows like that. So I’m optimistic”

He did warn about a “hollowing out” of the middle class, though, as income over the last few years has grown most for the richest. In discussion afterward, Barofsky echoed the sentiment and restated that the top one percent benefited from the bailout, but that 70,000 kids just got kicked out of the Head Start Program.

The three economists discussed various regulations that could rein in banks — including Dodd-Frank (which Barofsky, unlike Elliott, thinks will be worthless), size caps, a new version of the Glass-Steagall Act separating banking activities, and capital requirements. Heading off another Great Recession, they all agreed, is worth costing banks something. “How big should bank capital requirements be?” asked Cooley. “Big enough so that it doesn’t matter.”