Saving Mountain Dwellers from Wildfire

Will More Fuel Breaks on San Marcos Pass Protect Them?

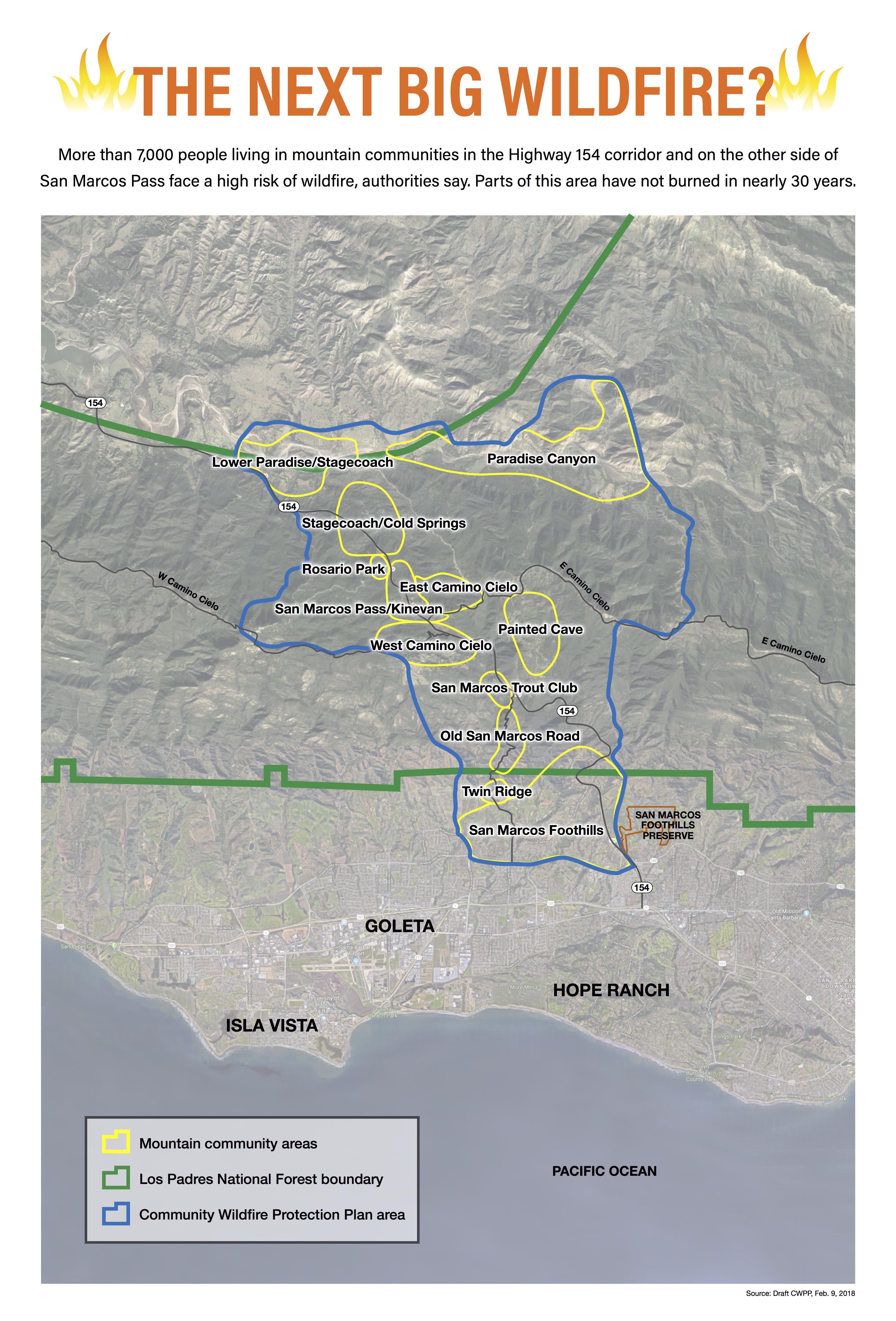

an area that hasn’t burned extensively since 1990.

Every major block of native chaparral on the South Coast mountainside has burned in this century, with three exceptions. The Gaviota Coast from Arroyo Hondo to Refugio Canyon hasn’t burned since the 1950s, and there’s no record of when the Hollister Ranch last burned. But the biggest threat to lives and homes today, authorities say, would be a wildfire on the steep slopes that run from the foothills of the eastern Goleta Valley up to San Marcos Pass and down the other side to Paradise Road.

Much of the chaparral on the south-facing slopes here hasn’t burned since the devastating Painted Cave fire, a “sundowner” blaze that was set near the pass by an arsonist in June 1990. It still ranks as the most destructive wildfire in Santa Barbara County, with one fatality and 640 structures lost. In 100-degree heat, the fire raced down-canyon in violent winds and jumped all six lanes of Highway 101.

“Among the fire chiefs and firefighters, we’re looking at San Marcos Pass as the place where it’s inevitable — in a short amount of time, we’re going to see the next iteration of the Painted Cave fire,” said Rob Hazard, a County Fire Department battalion chief and deputy fire marshal.

In all, more than 7,300 people live in 12 picturesque enclaves stacked like the layers of a wedding cake up and down both sides of the pass over the Santa Ynez Mountains. They include the San Marcos foothills, East and West Camino Cielo, Painted Cave, San Marcos Trout Club, Old San Marcos Road, and Paradise Canyon. Most are private in-holdings within the Los Padres National Forest. They contain more than 1,500 homes and outbuildings — hundreds of old wood cabins, dozens of modern homes, especially in the front-country foothills, and a sprinkling of big estates.

Efforts to address the looming fire threat, however, have been unable to produce a consensus among fire experts, homeowners, and other stakeholders. It has been a persistent, sometimes harsh, either/or debate, pitting those who insist more fuel breaks are the solution versus those who insist the top priority is for residents to “harden” their homes against fire.

Lives and property hang in the balance, and so do hundreds of thousands of dollars in potential state grants for wildfire protection. Meanwhile, residents anxiously watch the August temperatures soar.

“We listen to both sides and we can see both sides,” said Seyburn Zorthian, a longtime homeowner in Painted Cave, which sits atop a rough plateau, high on the mountainside. The community itself — about 100 homes and 300 people — narrowly escaped the 1990 fire that bears its name.

“I know there’s going to be some horrendous fire, and I sometimes just have to resign myself to losing everything,” Zorthian said. “But it’s a really nice community to live in. I really feel, here, like I belong.”

A Plan in Limbo

Rob Hazard is cochairman of a team of fire experts and community volunteers who have worked for two years to draft a 200-page wildfire protection plan for the San Marcos Pass–Eastern Goleta Valley communities. The $93,000 consultant’s fee was shared by the county and state, and the plan has been awaiting county review for months.

The San Marcos plan was billed as a collaborative effort among government agencies, community groups, and scientists, but two environmentalist groups, Los Padres ForestWatch and the Santa Barbara Urban Creeks Council, resigned from the team in protest earlier this year. Several of the scientific advisors called the plan a throwback to an “older approach” and implored the team to make significant revisions.

According to Chief Hazard, the plan identifies 250 acres, or one percent, of the 30-square-mile plan area, where vegetation would be thinned out or cut down, mostly on private land, to help protect mountain residents from wildfire. Thirty-eight separate projects are proposed, half of them along roadways. The vegetation along the roads would be cleared 10 to 20 feet on each side, chiefly along Highway 154.

If all these “fuel treatments” were contracted out, it would cost up to $80,000 to clear every 10 acres, Hazard said. Much of the work, however, would likely be done by county public works and fire department hand crews and community volunteers, with state and federal grants providing partial funding, he said.

The idea, Hazard said, is to thin out dense vegetation in strategic spots next to the communities where, in an average wildfire — not an extreme one — firefighters can make a stand, protect homes, evacuate residents, and save themselves.

“I have been in the front of many wind-driven fires,” he said. “The only thing that can guarantee we can get home safely at night is that we have space to work.”

At the same time, the plan states that 42 percent to 86 percent of mountain homes and outbuildings, depending on which community they are in, fall into the category of “low defensibility” in a wildfire, meaning it would be hard for firefighters to save them, especially in sundowner conditions.

Many residents have not replaced their wood shake roofs and siding, installed double-pane windows, placed ember-resistant screens over their attic vents, or even cleaned out their gutters, the plan notes. They haven’t removed wood fences and wood decks that can act as conduits for fire, or cleared a safe space around their homes.

“There are significant opportunities for wildfires to ignite, establish and destroy structures,” the plan states.

Jeff Kuyper, executive director of ForestWatch, a nonprofit conservationist group, together with Urban Creeks and the scientific advisors, have argued that the San Marcos Plan should be focused on retrofitting homes and improving evacuation plans, not on altering the natural landscape to fight out-of-control fires.

The county should aggressively seek state and federal grants to help mountain residents “harden” their homes and establish a “defensible space” around them, Kuyper said. Currently, no state money is earmarked for that purpose.

The plan recommends that the county develop an educational brochure on retrofits, but this is lip-service, the critics say.

“When I saw that, I felt tremendous discouragement,” said Richard Halsey, a scientific advisor for plan and a biologist who heads the California Chaparral Institute, a nonprofit research group based in Escondido. “I was under the illusion that we were all working to reduce the vulnerability of communities.”

Things fell apart in January after a few members disparaged the scientists in an internal email chain, suggesting they were not real experts, Halsey said. Kuyper quit the team soon after, and so did Dan McCarter, vice-president of Urban Creeks.

“The plan was very much tilted toward clearing of vegetation,” Kuyper said in a recent interview. “We keep doing the same thing over and over again. We can make all the fuel breaks in the world, but embers can travel far, and unless structures are fire-safe, that work is all going to be forgotten.”

August, the Hottest Month

While the debate simmers, so do the hot spells of summer.

The record seven-year drought, which shows no signs of lessening, has killed a lot of brush on the steep slopes along Highway 154, creating volatile conditions for fire. Because of prolonged heat, the moisture in the chaparral, monitored every two weeks by county fire officials, is hitting critical flammable levels. Cars climbing the pass often overheat and catch on fire, typically sparking four or five small fires yearly. And August is the hottest month of the year.

As Mike Williams, president of the Wildland Residents Association, representing six mountain communities, says: “It gets so hot up here, you can actually watch the plants start to wilt, as if you’d put them in an oven.”

Williams, a resident of Rosario Park, an enclave of 23 homes on the west side of 154, over the pass, carries a scanner so that he can receive immediate wildfire alerts. He is a self-proclaimed “huge advocate” of more fuel breaks; he says his association has obtained nearly $1.5 million in state and federal grants for such projects since the mid-1980s.

“You could have crews up here working around the year and it wouldn’t be enough,” Williams said.

In the past, about 1,500 acres of chaparral have been cleared by the county, Los Padres, and private landowners in the 12 mountain communities. That includes a piece of the Camino Cielo fuel break, which was created in 1970 by spraying Agent Orange, an herbicide left over from the Vietnam War, along 40 miles of the ridgeline road.

Yet a 2011 study of four Southern California forests, including Los Padres, found that fuel breaks stop fires only 47 percent of the time, at best — if firefighters can reach them. At least half of fuel breaks never even intersect fires, the study found. Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey, UC-Los Angeles and the Conservation Biology Institute of La Mesa, California, based their conclusions on 28 years of data, beginning in 1980; 640 wildfires occurred within the boundaries of the four forests during that time.

Firefighters know that fuel breaks won’t stop a wildfire on San Marcos Pass from blasting down the canyons like a blowtorch in 75-mile-per-hour sundowner winds. But fuel breaks, they say, can help them “flank” an unruly wildfire and “take the steam” out of it by setting backfires.

Los Padres National Forest recently drew up a plan of its own for new fuel breaks totaling 200 acres around the mountain communities of Painted Cave, Trout Club, Rosario Park, and Haney Tract, a community just west of the Trout Club. The work is ongoing and will cost between $200,000 and $300,000. For Painted Cave alone, a fuel break nearly a mile long has been approved.

Max Moritz, an advisor for the San Marcos Plan and a statewide fire specialist with UC Cooperative Extension at UCSB, said he was not opposed to creating some strategic fuel breaks near communities at risk. But an equal amount of time, effort, and money should go into helping homeowners retrofit their homes, he said.

Without doing that work, Moritz asked, “What have you really accomplished? You still have all these vulnerable structures that are going to be much more difficult to keep from burning …

“Climate change is going to lead to more, potentially large, more severe fires, and more communities exposed to fires,” Moritz said. “There’s a growing awareness among scientists studying fire that that’s separate from the problem of why homes burn and people die.

“The problem of fatalities and loss of homes hinges more on what we build in the wildland-urban interface, and how we get people out when there’s not a lot of time.”

Living in Wildlands

According to research by ForestWatch, more than 60 new homes (not replacement homes) have been built in the footprint of the Painted Cave fire since the fire reduced 5,000 acres to ashes, 30 years ago.

Nationally, the “wildland-urban interface,” or areas where homes are built in or near natural vegetation, grew by more than 12 million homes between 1990 and 2010, an increase of 40 percent, and added a third more land area, according to a study last year by researchers from UC-Berkeley, the University of Wisconsin, the U.S. Geological Survey, and other institutions. With more people living in such places, wildfires “will be hard to fight, and letting natural fires burn becomes impossible,” the study stated.

The lure of scenic 180-degree views and woodsy neighborhoods far from city traffic is unmistakable. Home prices in such remote areas are more affordable, too. But living in nature comes with built-in risks. A number of Painted Cave residents have had their fire insurance canceled or their rates substantially increased.

“This is a great place to live, except when it’s burning, and then all the factors that make it beautiful work against you,” said Kevin Buckley, chief of the Painted Cave Volunteer Fire Department, which has its own fire trucks and 22 volunteers.

“People do get freaked out,” Buckley said. “The biggest thing they want to know is, can they sleep tonight?”

Buckley is on the team that drew up the San Marcos plan. He estimates that Painted Cave has received up to $60,000 in public and private grants for vegetation clearance since 2009.

“This area is way better than it used to be, but not nearly where we need to be,” Buckley said.

Phil Seymour, a Painted Cave resident and a former seasonal firefighter with the Los Padres Hotshot crew, co-chairs the San Marcos planning team with Hazard. Since the late 1980s, he’s spent countless hours with a chainsaw, clearing the vegetation around Painted Cave.

“Conditions can be so extreme that there’s just nothing you can do,” Seymour said. “What we’re planning for, to give us a best chance at surviving, is a reasonable worst-case fire. The whole point of the fuel clearing is so that when it gets here, it won’t be a solid wall of flames.”

It was a fuel break that stopped the Lookout Fire from burning down Painted Cave on a windless morning in October 2012, Seymour said. Paying homeowners to “harden” their homes would improve their chances, but it wouldn’t necessarily save the structures, he said.

“If there’s any chink in the armor, the fire’s going to get in,” Seymour said. “There are no guarantees. If the window’s open, that’s a problem.”

But other residents object to what they view as scars on the landscape that mar the natural look. They’re concerned about the highly flammable grasses that have invaded those cleared areas. And they fear that fuel breaks are giving their neighbors a false sense of security.

Tom Dudley, a UCSB marine biologist who specializes in invasive plants, said he watched the Jesusita Fire of 2009 jump Windy Gap, a large fuel break near the San Marcos Pass, “six or eight times.”

“You don’t protect from fire from the forest in; you protect from the structures out,” Dudley said. “It’s the embers that burn down houses, not the heat from the fire.”

Dudley’s wife, Carla D’Antonio, is a UCSB professor of environmental studies and an advisor for the San Marcos plan.

“There’s not a strong will to deal with issues other than clearing shrubland,” she said. “It’s easy to get grants to do that. It shows the public that you’re doing something. It’s kind of a statement about human domination of the landscape.”

A House Is Dry Fuel, Too

No one disputes that Painted Cave is a tinderbox. The roads are poor, and much of the community is tightly packed. Piles of firewood and dead tree trunks are lying around near homes. Many homes have wooden fences and decks and exposed wooden eaves. Some are old cottages with wood-shingle siding. There are carpets of pine needles and tall weeds in some yards.

All of the homes in Painted Cave have fire-resistant roofs, and many property owners have small private water tanks connected to hydrants. But the San Marcos plan gives 82 percent of the structures in the community a “low-defensibility” rating.

Seymour has his own fire hose that he can hook up to a neighbor’s swimming pool; they share a pump. Dudley and D’Antonio estimate that they have spent about $35,000 to retrofit their home; the biggest expense was the tempered glass windows and some fiber cement siding. Every two weeks, they clean out their gutters.

D’Antonio said she is not opposed to all fuel breaks, but, she asked, “How many do you need, and at what point do they degrade the environment?”

“It’s much harder to convince people they really need to pay attention to their own property, cut down their half-dead trees and their eucalyptus, understand that their house is among the driest fuel on the landscape, and plan accordingly to make it less flammable,” she said. “People up here want to have these fuel breaks because it takes some of the responsibility off themselves.”

For Anne Eldridge, a homeowner who lives on the lower section of Painted Cave, where the road winds steeply uphill with many switchbacks, it’s a question of dollars and cents. She’d like to upgrade her sprinkler system and stucco her wood house. But Eldridge is retired and doesn’t have tens of thousands of dollars.

Meanwhile, the plan for protecting the San Marcos Pass communities could go up in smoke. Feelings have been hurt. The two sides have stopped talking. And the state is handing out $200 million this year in grants for forest thinning.

“Ultimately,” Hazard said, “what protects communities are firefighters.”