Americans at Play at Sullivan Goss

Exhibition Celebrates Role of Play in American Life

Few categories are as slippery—or as interesting—as the seemingly simple concept of “play.” Covering activities that exceed the range of such comprehensive terms as “culture” and “society,” play is mostly defined through negation, by specifying what it is not. Play is not work, not ordinary life, not “reality,” and above all, not mandatory. As the fundamental voluntary activity, play may be the most ubiquitous form of practical freedom we know. In this touching and provocative group exhibition, works of art depicting play appear alongside vintage toys and other reminders of childhood games that resonate both with each other and with the memories of those who observe them.

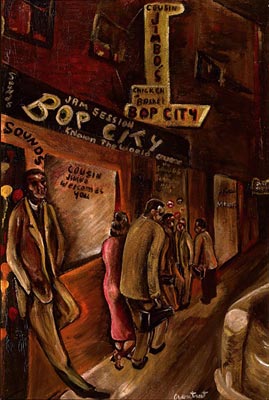

In the first room, Frank Goss has arranged a selection of works, mostly paintings, from the last 100 years that show various American pastimes. In the second, Susan Bush has put together work by contemporary artists, with some pre-existing pieces and other things commissioned specially for the show. The first room conjures all kinds of unexpected apparitions, as putting play in the foreground seems to call forth whole worlds of experience. Several images include the figures of servicemen on leave from the military. In Dorothy Sklar’s watercolor “The Great Lover” (1944), uniformed soldiers dominate the foreground of a scene outside a Southern California movie theater. Guy Goodman Howard’s “Sailors a Steppin WW2 Street Dance” (c. 1941) shows a young girl waving poignantly at the viewer as couples boogie in the street around her. And the large (56” x 72”) “Central Park, Bethesda Fountain” by Henry Shnakenberg gives the theme of war and play a sweeping, cinematic treatment. Together, and in the company of such other haunting images as “Jimbos Bop City, San Francisco” (1956) by Joseph Overstreet and Dan Lutz’s extraordinary, darker-than-Hopper “Pool Hall” from 1938, the paintings create a profound sense of the fragility and evanescence of life.

For the contemporary artists exhibited in the back room, play’s frame of reference is more about visual stimulation than it is about the human condition. With the exception of Sally Storch, whose marvelous “Crossword” (2010) captures the inwardness of solitary pastimes, these recent pictures and objects celebrate the seductive surface. Whether it’s Nathan Sawaya’s clever and evocative sculpture “Jacks” (2010), which is made entirely of Lego, or Melissa Chandon’s elegant, Thiebaud-esque “Swimmer with Green Cap” (2010) the emphasis of the show falls on amplifying the aesthetics of the everyday through color. Under the summer sun, or what there is of it, these images radiate pleasure.