Why Did Highway 192 Separate Montecito’s Mandatory and Voluntary Evac Zones?

County Emergency Managers Start to Explain Their Much-Dissected Decision

In the days leading up to the January 9 storm, Santa Barbara County officials wrestled mightily with how best to protect the residents of Montecito from the predicted flooding and debris flows that threatened the community: Should they simply warn citizens of the danger? Should they evacuate all 30,000 residents? Or should they attempt to clear out the most at-risk neighborhoods at the base of the fire-scarred mountains and put everyone else on high alert?

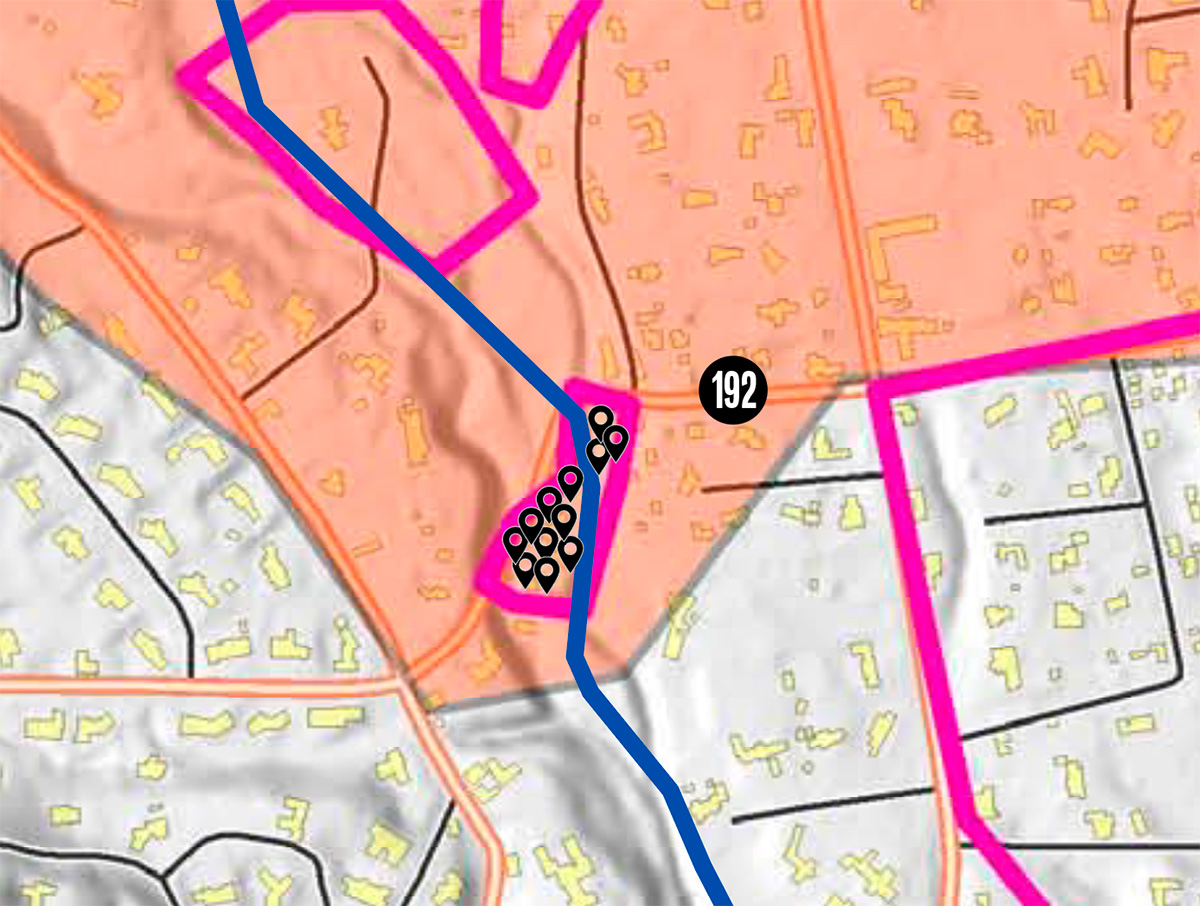

As the forecasts grew more threatening, county emergency managers decided to draw a hard line at Highway 192, ordering everyone north of it to evacuate and advising everyone south to be prepared to leave at a moment’s notice. Nineteen people south of the line died when the explosive downpour pounded the denuded hillsides and sent fast-moving battering rams of boulders and mud crashing through their homes.

Montecito has five creek channels running north to south. Though no one had predicted the intensity of the storm, all agreed that the greatest danger on January 9 would be from gravity-powered, flood-fed debris flows coming down those channels. Yet the mandatory evacuation orders were drawn along the lines of Highway 192, a main road that runs east to west along a topographically irrelevant area in Montecito. Increasingly, residents are questioning why this decision was made and how evacuation decisions will be made in the future.

At a community forum last Thursday, February 8, some in attendance raised the issue. “Whoever was in charge of this was probably a good person, but good people fuck up,” said audience member Dave Mackenzie. “I want to know who was in charge of this, and I hope we get some answers, because people were not looking at this properly.”

Sheriff Bill Brown, whose department is ultimately responsible for drawing and enforcing evacuation boundaries, has struggled from the day of the tragedy to communicate the rationale behind the Highway 192 border. He’s repeatedly stated that inquiries over the issue are a disservice to first responders. This week, county officials finally released the map they relied upon for their decision, but even this map tells mixed stories.

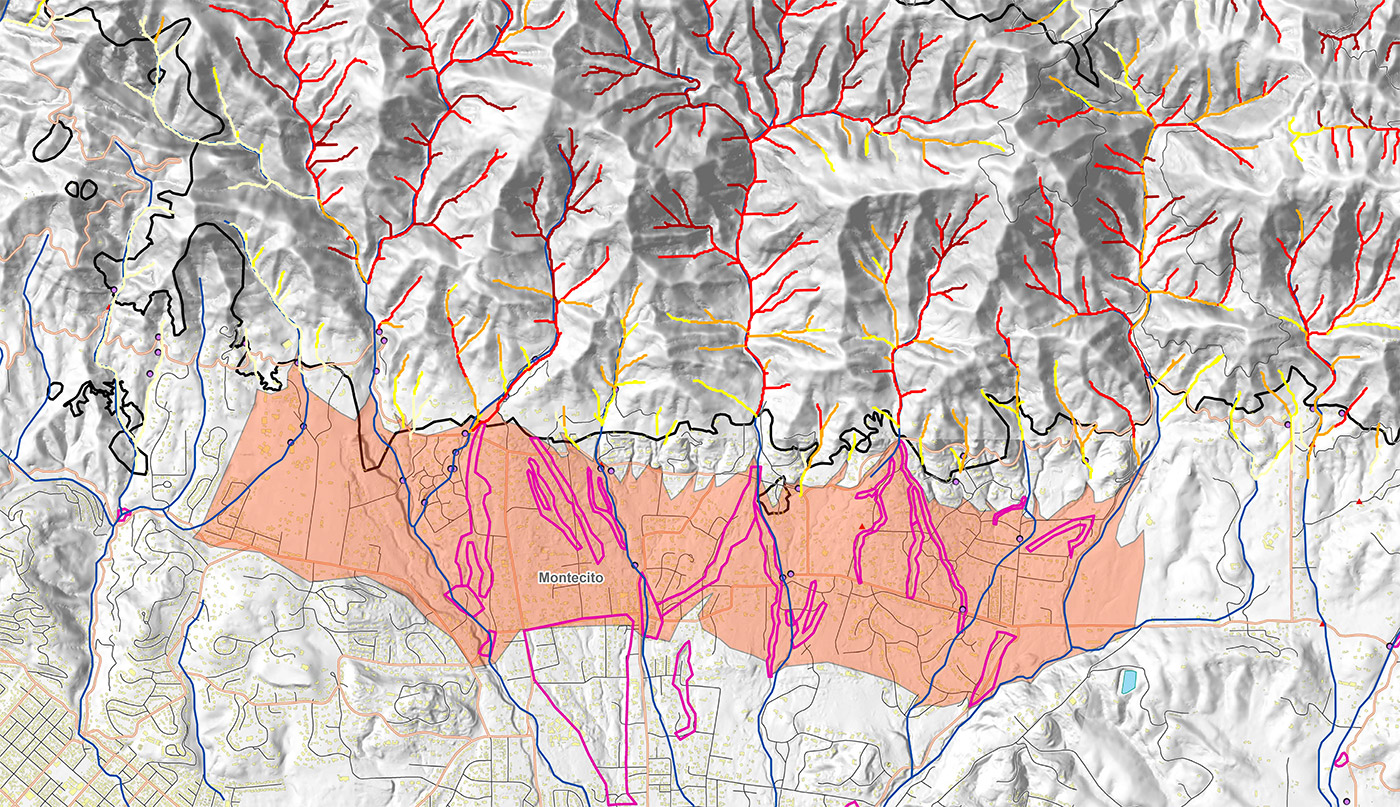

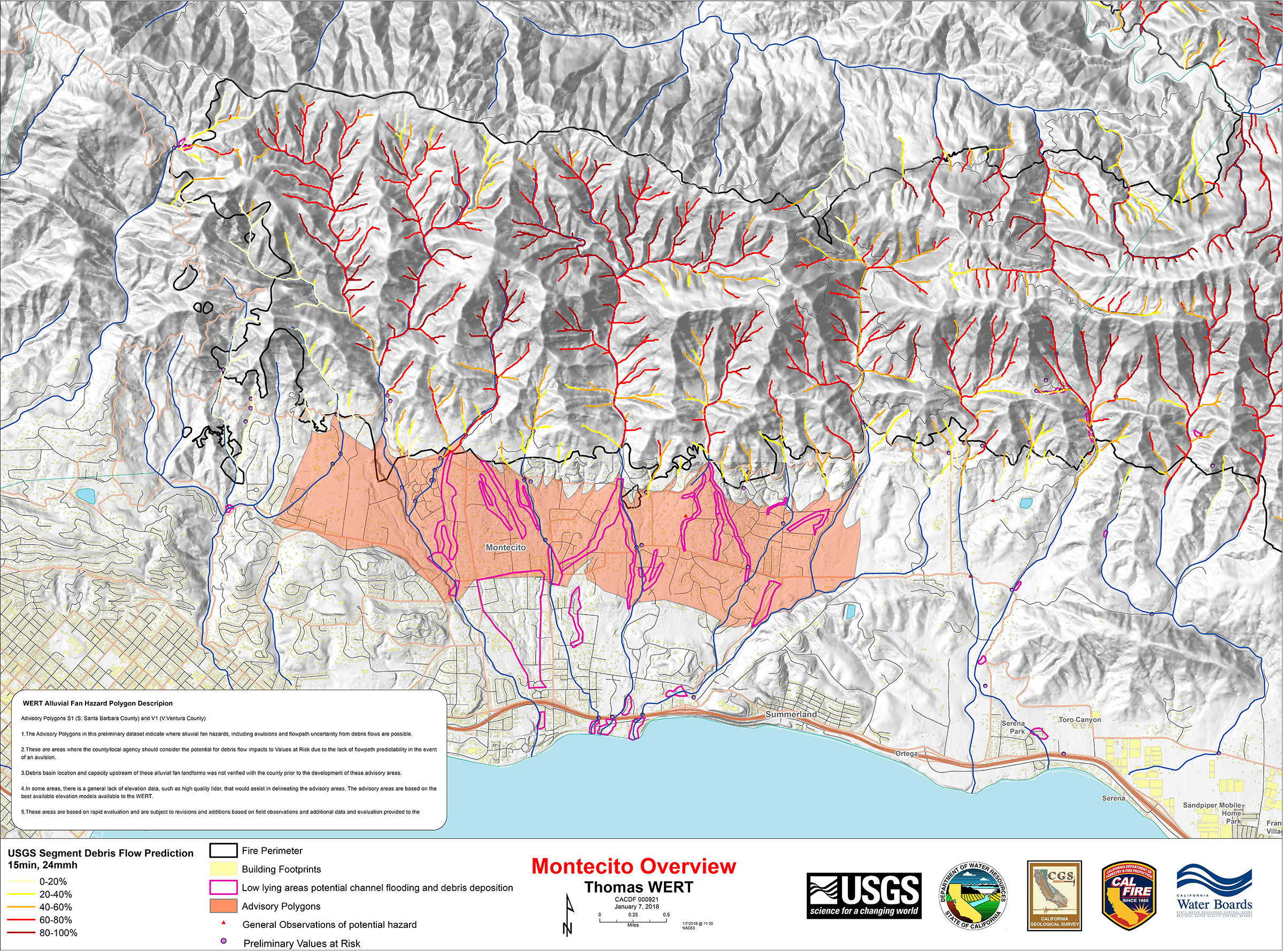

State scientists with the Thomas Fire WERT (California Watershed Emergency Response Team) supplied the damage forecast map to local authorities on the afternoon of Sunday, January 7, just a few hours before the final mandatory and voluntary orders were issued, 30 hours before the rain. WERT spokesperson Len Nielson said the team had recognized the impending danger and rushed to put together a best-guess prediction for where flooding and debris-flow hazards could concentrate in a storm that delivered up to one inch of rain per hour. Such studies typically take weeks or months to complete. “But we said, hey, we’ve got to get this information to the county to protect lives,” Nielson said. County officials also say they initiated the study.

The pink-colored swatch in the map above represents where floodwater and debris might exit creek channels and spread across the region’s alluvial fan, Nielson explained. From east to west, much of the danger zone’s southern edge traces just below Highway 192. Near San Ysidro Road, it starts to bleed half a mile or so south of the evacuation boundary. The areas traced in thick magenta lines show low-lying areas where scientists believed the flows could head toward and pool. Post-disaster surveys reveal these areas were indeed inundated with water, mud, and boulders.

According to the map, 14 of the 23 victims of the 1/9 Debris Flow, as the disaster has now been officially named, lived in neighborhoods designated at-risk by the WERT hydrologists and geologists. Their homes were located both within the general alluvial-fan hazard region highlighted in pink, as well as within the especially dangerous low-lying areas outlined in magenta.

Nielson emphasized that the map provided debris-flow predictions for a one-inch-per-hour rain event, not for the storm that dumped nearly four inches of rain above Montecito, including the 0.54 inches that blasted loose soil in five minutes. “If we knew we were going to get four inches, [the map] would have been totally different,” he said. “In a one-inch storm, we thought the people below the [pink] polygon would have been fine.”

While the National Weather Service had earlier in the week predicted a one-inch storm with moderate certainty, by Monday afternoon, January 8, its forecast was upgraded with increased confidence to two to four inches of rain in the coastal areas and four to seven inches in the mountains.

During the gatherings last Thursday, February 8, Brown justified the Highway 192 line by citing a USGS map published January 5. “One thing that hasn’t gotten out in the media and hasn’t resonated with the community is that we received maps from the U.S. Geological Survey that showed where the estimated destruction would be from a major storm,” he said to television cameras and an audience of 200-300 that packed the Montecito Union School auditorium. “And the estimated destruction of the storm was above East Valley Road. In fact, it was above East Mountain Drive. It was toward the base of the mountains and parts of the community just in that area.”

Brown stated that the county’s evacuation system, which grids communities into easily identifiable rectangles that can be emptied safely within two hours, was developed after the Jesusita Fire and is meant to be used in any emergency situation, not just fire events. “That grid system was overlaid on top of the map where the destruction was predicted,” he said, and Highway 192 was selected as the demarcation because it was the only clear arterial through town.

Brown, however, was mistaken in his interpretation of the USGS map he cited. Also, it was actually the WERT map that was used. The USGS survey of federal land within the Thomas Fire burn scar was “designed to assess the potential for debris flow in the locations where debris flows initiate (i.e., where they form and get larger),” USGS research scientist Dennis Staley clarified Monday. “We do not assess potential damage, runout paths, and/or the area that would be inundated during a debris-flow event once the flow exits the mountains.” Staley said Brown would be getting a letter from his agency’s managers asking that he “stop misrepresenting our science.”

Undersheriff Bernard Melekian spoke for the Sheriff’s Office during the county’s evacuation boundary deliberations. He stressed that the WERT map was only one of innumerable planning documents and factors that went into the Highway 192 decision, though it was “probably the most definitive map product we had on January 7.”

Great care and thought went into the decision, Melekian said, with all options thoroughly scrutinized. Emergency managers knew there needed to be some kind of evacuation, he said — the danger of not having one was simply too great. They considered clearing out the entire community, but worried about the “crying wolf” effect if the storm never materialized. “We do this and nothing happens, we are going to lose credibility for next time,” he explained. Authorities also discussed creating mandatory evacuation zones around creeks, but ultimately decided they were too under the gun. “We could do it, but to do it exactly would take a very long time,” Melekian said. “We couldn’t do it in a few days in any meaningful way.” The county is now in the process of drawing those lines.

Melekian also emphasized how the county had never before evacuated residents ahead of a flood. He talked about how emergency managers — navigating uncharted territory and already overworked after the Thomas Fire — performed to the best of their abilities with all the information at their disposal, including the WERT map. “That map was a statement of possibility, not a statement of fact,” he said, and the Highway 192 demarcation that came from it was the clearest, safest way for the Sheriff’s Office to communicate different levels of danger to the public. Ultimately, Melekian said, “The storm that was forecast, and the storm that we prepared for, was not the storm that we got.” Seven thousand people received mandatory orders; 23,000 received voluntary warnings.

Brown described the changes his department is making in how and where it communicates debris-flow evacuations. (A full explanation of the changes can be found here.) He addressed lingering concerns over confusion in the language that warned Montecito residents in the voluntary evacuation zone. “For some, the focus was on the ‘voluntary’ rather than the word ‘evacuation,’” Brown said. “The reality is some people misinterpreted that and believed there was a measure of safety there that there really wasn’t.”

The warnings issued by the county’s Office of Emergency Management to residents in the voluntary zone read: “People in these areas should stay alert to changing conditions and be prepared to leave immediately. If the situation worsens or you feel threatened, leave immediately or take protective actions.”

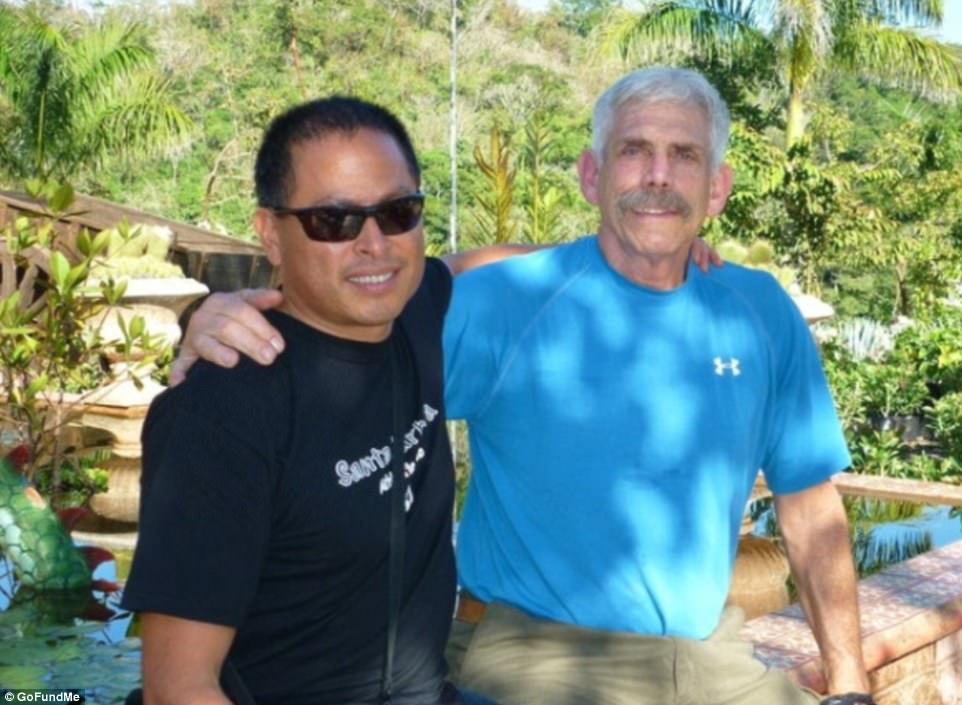

Brown’s words stung Lalo Barajas, owner of Rose Café on the Mesa, who had lived with his longtime partner Peter Fleurat, a nurse and caregiver, on Hot Springs Road, in the voluntary zone. They didn’t misinterpret anything, Barajas said.

As instructed by a mandatory order from the county, the couple had evacuated during the fire, and they received the warning to remain vigilant during the January 9 storm. Both lived through the 1995 flood and so thought they knew the danger. They packed their cars with cherished possessions — mostly paintings — and parked them outside their gate facing the road, ready to flee at any moment.

Barajas went to sleep that night, but Fleurat, 73, stayed up to monitor Montecito Creek just a couple hundred feet from their home. “He spent all night vigilantly watching,” Barajas said. “When it got bad enough, we were going to leave.” By the time the couple received cell phone alerts that disaster was imminent, it was too late. Their bedroom wall “blew open,” and they were dragged into the mud. Fleurat’s body was found half a mile south, near four others, at the corner of Hot Springs and Olive Mill roads.

Barajas said had they had been ordered to evacuate, they would have. He said the county’s explanations for the Highway 192 boundary is just “backtracking,” and he called Brown’s statements salt in the wound. “It wasn’t comforting,” he said. “I’ve heard from people over and over again that the lines didn’t make sense.”

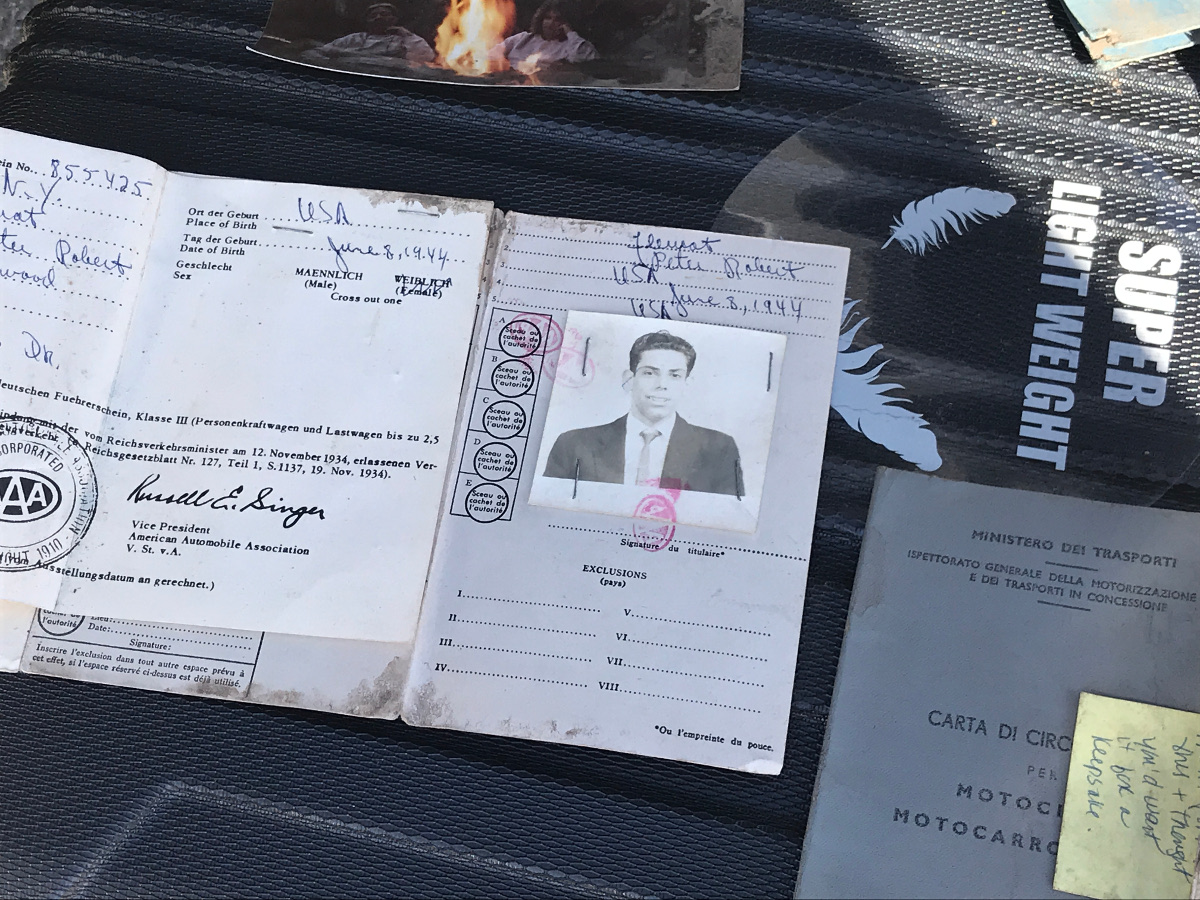

Barajas lost almost everything in the storm, but somehow, several possessions landed undamaged downstream — four unbroken bottles of wine, a stack of tablecloths he’d bought in Chiapas, Mexico, blossomed plants, and Fleurat’s original passport. When he went back to their property, he found their two kayaks had hardly moved at all. “I can’t figure it out,” he said.

Kelsey Brugger contributed to this report.