Another Year of the Shark

To Fish or Not to Fish

The year 2009 was the year of the shark, and 2011 is shaping up to follow. With increasing knowledge of plummeting numbers in shark population counts, conservation groups have begun putting pressure on commercial fishermen to limit their daily shark intake.

This follows in the wake of President Obama’s signing of the Shark Conservation Act, which outlaws shark finning in U.S. waters. (This is the practice of removing a shark’s fins, then throwing the still-living shark back into the water.) While finning is outlawed, shark fin soup can still be bought in many cities, including nearby Los Angeles.

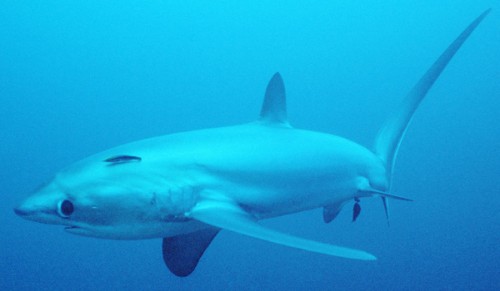

In Santa Barbara, thresher sharks are a specialty. We find them on the menu at numerous restaurants and can even buy them in grocery stores. Thresher sharks are unique in that they are partial endotherms; they are partially warm-blooded. They are capable of hoarding heat and then using it to aid them in short bursts of speed while hunting. Only four official thresher shark attacks have ever been recorded, and of those one was provoked. They are also one of the few shark species known for breaching, or jumping completely out of the water.

Fishermen and some biologists, like Craig Heberer of the National Marine Fisheries Service in Carlsbad, quoted in the San Diego Tribute, say the thresher shark population has remained stable and even increased over the years. The shark remains popular with sports fishermen, as it grows anywhere from 10 to 20 feet in length, but both fishermen and the Department of Fish and Game say it is no longer widely commercially fished. Because thresher sharks are local, eating them rather than imported species that need to be shipped saves both money and the environment, they say.

For commercial fishermen, loss of income is another factor. With the economy as it stands, few fishermen, if any, can afford to lose any part of their catches. Thresher shark yields around $13 per pounds and can weigh over 500 pounds. Demand for shark meat continues, as it is low in fat and high in protein, making it seem a healthy choice for many people.

Meanwhile, conservationists like those at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) have a list of reasons why the sharks shouldn’t be fished. They cite the slow growth rate of all shark species, with thresher sharks taking up to 13 years to reach maturity. All sharks can be considered endangered. The IUCN describes the common thresher shark as “vulnerable” on its red list. According to IUCN’s Web site, this indicates that a species is “considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the wild.”

While fishermen contend that the number of thresher sharks has increased over the years, some researchers, like the biologists at the IUCN, say the true number of sharks can’t easily be counted and that the sharks haven’t responded well to fishing pressure. “Shark Free Santa Barbara” alleges that 73,400 pounds of thresher shark were caught in Santa Barbara alone in 2008 — more than anywhere else on the West Coast of the United States. In addition, the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s yearly Seafood Watch List says to avoid consuming all species of shark, both to protect populations and because of concerns over mercury levels in shark meat. Spiny dogfish from British Columbia is listed as a “good alternative.” The IUCN has been monitoring the population through the use of mitochondrial DNA.