Nukes of Hazard: Vandenberg, Star Wars, and North Korea

Is Vandenberg Air Force Base Our Best Defense or Our Greatest Risk?

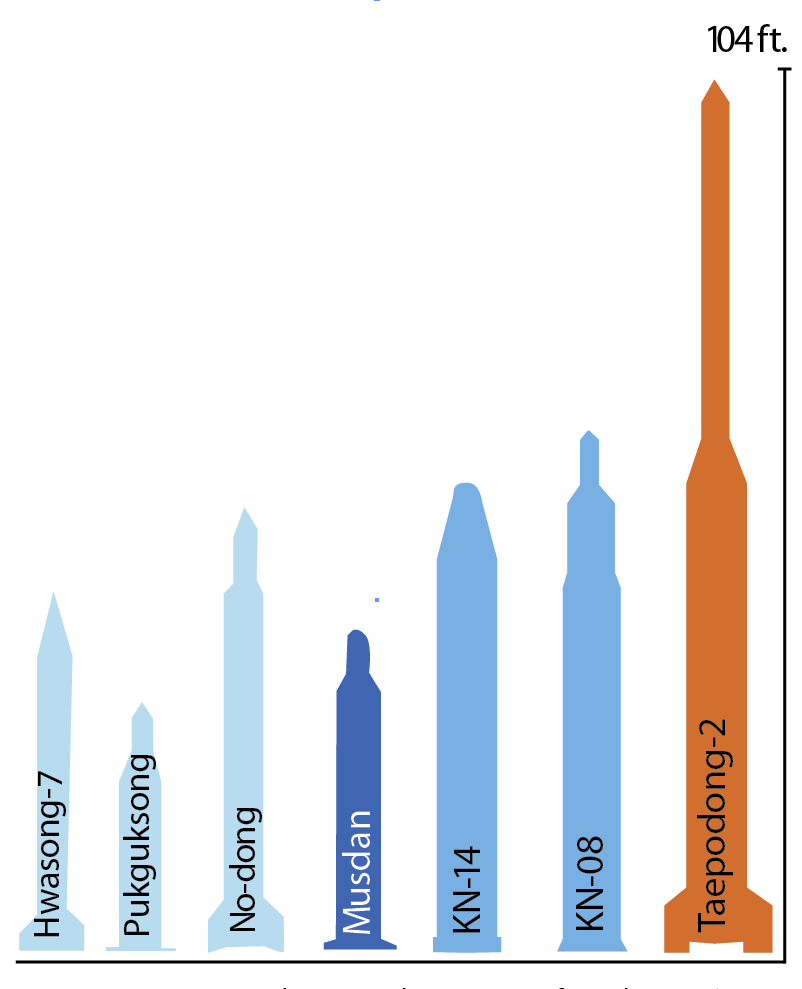

This spring, as American warships and submarines gathered offshore, Kim Jong Un, North Korea’s baby-faced dictator, threatened to reduce the United States “to ashes” with “invincible Hwasong rockets tipped with nuclear warheads” if even a single bullet was fired toward his country. The threat, like so many from the Kim dynasty, felt empty and overplayed. North Korea was still years away from building a missile capable of getting anywhere near the U.S. Or so we thought.

On May 14, North Korea tested a new ballistic missile with what American analysts called “stunning success.” Shot nearly straight up, the Hwasong-12 reached an altitude of 1,312 miles above Earth before harmlessly splashing down in the Sea of Japan. Had it been fired on a flatter trajectory, it would have flown approximately 3,000 miles, putting the U.S. Air Force Base in Guam 2,200 miles away well within striking distance. The demonstration, wrote aerospace engineer John Schilling at Johns Hopkins University, “represents a level of performance never before seen from a North Korean missile.”

This fast-shrinking gap between Kim Jong Un’s bluster and North Korea’s true military might has thrown the Trump administration and our traditional Southeast Asian allies into a panic. And it’s heightened jitters among the American public, especially those living on the West Coast and in Hawai‘i, where echoes of Pearl Harbor are now reverberating at a higher pitch. But clear information, let alone assurances, is not forthcoming from the White House. Trump ominously warned reporters in April the U.S. might very well face a “major, major conflict” with North Korea. “Absolutely,” he said. Yet his cabinet continues to stress diplomacy over intervention. These contradictory approaches only add to an increasing sense of confusion.

Meanwhile, the so-called Hermit Kingdom is preparing for yet another underground nuclear bomb test. It would be its fourth in five years; the most recent was in September. The last three tests generated Hiroshima-size explosions. Experts also now believe the country could be able to produce a new nuclear bomb every six weeks, and could, in just a few more years, build a warhead capable of reaching Seattle.

Many in Congress seem in the dark, too. So much so that last week, a bipartisan group of 64 members sent a letter to the president, asking what steps he and his cabinet were taking to engage in direct talks with North Korea. “In such a volatile region, an inconsistent or unpredictable policy runs the risk of unimaginable conflict,” the letter reads. It also emphasized the 30,000 U.S. service members and more than 100,000 U.S. civilians who reside just over the border in South Korea.

Situated in the middle of all this — geographically, strategically, and symbolically — is Santa Barbara County’s Vandenberg Air Force Base. The nearly 100,000-acre space launch facility is one of only two locations in the entire country to house the specialized missiles that represent our first, last, and only line of defense against an incoming nuclear warhead fired specifically by North Korea or Iran.

This Tuesday afternoon, Vandenberg conducted a test of the troubled Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system. It was a success and reinvigorated a Pentagon program dogged by expensive delays and embarrassing flops. But serious questions remain about the reliability of the $40 billion system and our ability to protect ourselves from a sneak attack by a rogue state.

Flying White Elephants?

The GMD program is a direct descendent of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) proposed by President Ronald Reagan in his famous 1983 Star Wars speech that envisioned a security system capable of shooting nuclear missiles out of the sky. Reagan criticized the longstanding “mutual assured destruction” doctrine that U.S., Russia, and China had long adhered to as a nuclear deterrent — the assumption that no country would launch a first strike for fear of a devastating counterattack. Reagan wanted a Star Wars system as backup. Some of the SDI’s earliest test launches took place at Vandenberg, and a commemorative limestone and bronze bust of Reagan still looks out over its sprawling missile range.

The Clinton administration continued funding the project that eventually became the GMD program but opted not to make it operational because of its technical difficulties. When George W. Bush took office in 2001, however, he fast-tracked GMD to fulfill a campaign promise. Then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld exempted the missile agency overseeing the project from the Pentagon’s normal testing standards. The final products, hardly more than advanced prototypes, were then quickly approved, locked, and loaded into underground silos — 32 at a base in Ft. Greely, Alaska, and four at the north end of Vandenberg. This rush job is the reason for GMD’s many failures, according to top government officials from several administrations.

GMD interceptors, as they’re called, are 60-foot-tall, three-stage rockets affixed with a five-foot, 150-pound “kill vehicle” on their nose. (A multistage rocket utilizes two or more sections with their own engines and propellant to reach a desired speed and altitude.) In the event of an attack, the interceptor would blast toward the incoming warhead as it entered space. Just before the warhead was about to begin reentry — the “midcourse” of its journey — the kill vehicle would separate from the interceptor and fly toward its target at four miles per second. At that velocity, a direct hit would obliterate the warhead: no need for explosives. The whole exercise is comparable to striking one speeding bullet with another.

What could possibly go wrong? Since 2004, and with this week’s test, the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) has conducted 10 highly scripted mock attacks. Dummy nukes were launched from a known location at a set time with a prearranged trajectory. They were even fired at a specific time of day so the sun didn’t blind the interceptor’s navigation system. Still, the interceptors and their kill vehicles, built by Raytheon and all launched from Vandenberg, missed their marks six out of those 10 times due to a host of engineering issues — thrusters malfunctioned, fuel burned poorly, separation went wrong, etc. “If these tests were planned to fool U.S. defenses, as a real enemy would do, the failure rate would be even worse,” said Philip E. Coyle III in an email exchange with The Santa Barbara Independent last week.

Coyle is a former director of operational testing for the U.S. Department of Defense and a steady critic of GMD. He noted that the system’s performance rate had actually gotten worse over time since it was first tested in 1999. But he also acknowledged the overwhelming challenge of the mission itself. “Missile defense is the most difficult technical problem the Pentagon has ever faced,” he said. The Department of Defense has been trying to develop missile defenses ever since WWII when Nazi Germany launched missiles at London and Belgium. We’ve been trying to solve this problem for roughly 70 years.”

Coyle nevertheless questioned the wisdom of throwing more time, effort, and taxpayer money at the problem, especially if the U.S. continues to put missile defense before diplomacy. “In response, America’s adversaries are likely to build more and more long-range missiles so as to overwhelm U.S. strategic defenses,” he said. “Exactly the opposite of what we would want.” Given the low reliability of our fleet, U.S. generals have articulated a “shot doctrine” of four interceptors for every one incoming warhead. That means a volley of 10 rockets would quickly deplete our defenses. North Korea is reportedly already in possession of enough enriched uranium to make precisely that number of nukes.

Truth or Consequences

This week’s $244 million GMD test was the first attempt since January 2016, which was a failure. The Pentagon, however, tried to hide that fact. Immediately after the 2016 flight in which the interceptor was meant to conduct a close flyby of the mock warhead, the MDA, Raytheon, and other missile contractors issued press releases gushing over the flight’s “success.” In reality, the interceptor veered wildly off course. The truth was only made public seven months later, when the Los Angeles Times ran a report sourced with anonymous Pentagon scientists. Before the story was published, MDA director Vice Admiral James D. Syring had told a Senate defense appropriations subcommittee that the test “enhanced” the agency’s confidence in the $40 billion GMD system.

In a telephone press conference hosted last week by The Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, John Tierney, former chair of the House subcommittee overseeing the missile defense program, said he expected the Pentagon to claim this Tuesday’s test a success, regardless of the actual outcome. During previous GMD hearings on Capitol Hill, he said, he witnessed “a lot of obfuscation, understatement, and overstatement” by military brass on the subject. The Union of Concerned Scientists, The National Academy of Sciences, and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have all voiced varying degrees of skepticism over the assurances given by Pentagon officials to lawmakers. Just a year ago, the GAO, a nonpartisan investigative arm of Congress, said the system’s performance had been “insufficient to demonstrate that an operationally useful defense capability exists.”

Vandenberg personnel referred all requests for information made by The Santa Barbara Independent to MDA Director of Public Affairs Chris Johnson, who declined to answer any questions, citing time constraints of his staff. In a prepared media statement, Syring called Tuesday’s mission, which scored a bullseye hit on the dummy warhead, “an incredible accomplishment” that demonstrated the U.S. has “a capable, credible deterrent against a very real threat.” He said he was immensely proud of the “warfighters” who executed it.

Representative Salud Carbajal, from Santa Barbara’s 24th congressional district, asked his own set of questions when he was grilling the White House budget director Mick Mulvaney last Tuesday at a House budget committee hearing. Why, Carbajal wanted to know, was the Department of Defense not subjected to the same close scrutiny as social programs singled out by the White House as “waste”? Mulvaney promised that the president would be taking a careful look at the department to identify any excess spending.

Later in an interview, Carbajal said his constituents were unnerved by Trump’s baiting rhetoric toward North Korea that could lead to a misguided war. “This president just doesn’t get it,” Carbajal continued, citing how Trump recently disclosed the locations of U.S. nuclear submarines to the controversial, volatile president of the Philippines. Carbajal will travel to South Korea this week and visit its northern border to “better understand the dynamic and threat that exists.”

Grazing at the Trough

The Fiscal Year 2018 budget released this Tuesday dictated a $54 billion increase in defense spending, including $10.2 billion for “weapons activities to maintain and enhance the safety, security and effectiveness of our nuclear weapons enterprise.” Rick Wayman, director of programs and operations for the Santa Barbara–based Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, calculated that with this increase, the U.S. government is on track to spend more than $1 trillion during the next 30 years modernizing its aging nuclear arsenal. That equates to nearly $4 million per hour.

It’s not clear how exactly this money will be divvied out, but early plans exist to increase the GMD fleet to 100 interceptors, some of which could be stationed at Vandenberg. A third site is also being explored. Back in 2014, current Attorney General Jeff Sessions — then a Senator from Alabama, where missile-defense jobs are heavily concentrated — was among those lobbying hardest for an expanded system, the Los Angeles Times reported. As a senior Republican on the Senate subcommittee responsible for missile defense, he repeatedly resisted efforts to slow the production of the rockets and often warned about the threat posed by North Korea.

Riki Ellison, chair and founder of the Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy outfit based in Virginia, was in Santa Barbara for the GMD test. Ellison conceded the program isn’t perfect, but it’s better than nothing. “If we didn’t have this system today, we’d already be at war with North Korea and China,” he declared. “It’s been worth the sacrifice of money and time.” Ellison said that Alaska’s Ft. Greely interceptors would be the first line of defense since an attack from North Korea would most likely come over the North Pole, a shorter distance between the two countries. Vandenberg’s interceptors are designed as backup in case some enemy rockets get through. “That’s why they’re so important. We should be looking at putting more interceptors at Vandenberg,” he said. “Why would we not?”

Vandenberg plays a critical part in our offensive capabilities, as well. With the vast Pacific Ocean as a safe zone, it serves as the main testing ground for the U.S. arsenal of nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). The U.S. Air Force operates 450 Minuteman missiles — 150 at three sites in Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota — and every few months (or sometimes more frequently) one is loaded onto a truck and driven to Santa Barbara for a dry run. Fitted with test instruments, they’re lobbed 2,500 miles to a test range in the Marshall Islands. The flights serve the dual purpose of keeping the fleet finely tuned and sending a message to our adversaries that the United States always has hundreds of nuclear rounds in the chamber.

The Danger Zone

Does that, then, make Vandenberg Air Force Base a potential strategic target for North Korea? Jon Wolfsthal, a senior nonproliferation adviser to President Barack Obama, says no. “If North Korea launches at the United States, it’s not going to be a strategic attack,” he said. “It would mean they were in a suicidal death spiral, so I’d be much more worried about Washington, New York, or even U.S. Strategic Command in Omaha.”

Wolfsthal said he has precious little faith in the effectiveness of the GMD system — “almost none.” Obama was also aware of its limitations. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be trying to improve it, Wolfsthal continued. “But we shouldn’t oversell its capability. That gives us a false sense of being invulnerable, and if we believe we’re invulnerable, we might do something dangerous.” Wolfsthal said he lacks confidence that the current administration grasps these distinctions.

North Korea has come a long way from its days of begging, borrowing, and stealing materials and plans for missiles that could barely get off the ground, Wolfsthal observed. The country has evolved from building knock-off, short-range Soviet-era rockets — “basically tinker toys” — to fabricating a multistage rocket that put a satellite into orbit last year. “Failure is a good teacher,” said Wolfsthal. Additionally, during military parades in Pyongyang in 2012 and 2013, Kim Jong Un showed off a replica of a three-stage missile with a theoretical range of 7,150 miles. In 2015, he displayed a mock-up of a two-stage ICBM with a predicted range of 6,200 miles. As a point of reference, San Francisco is about 5,500 miles from North Korea. “We can see a trajectory that poses a direct threat to the United States in five or so years,” Wolfsthal said. “And Vandenberg is going to be busy for a long time. It’s got serious job security.”

Don’t Know Much About History

As we look ahead, it’s important to remember what got us here in the first place. What does North Korea want? Why does it hate America? “These things go waaaay back,” said UCSB history professor Kenneth Hough, all the way back to the late 19th century; Japanese, Russian, and Chinese imperialism; and bloody occupations of the Korean Peninsula, a key strategic position among neighboring countries jockeying for territory.

Out of this repeated subjugation grew a deep sense of Korean nationalism and a desire to fortify the country against further outside influence. After World War II, the Allied powers divided the country, with North Korea heavily supported by the Soviet Union and the South protected by the United States and its European and Australian allies. The Korean War began in 1950 when North Korea invaded the South in an attempt to unite the country under communist control. “The Korean War is something that most Americans don’t remember, unless they think of reruns of M*ASH,” said Hough. “Two million North Koreans were killed by the U.S. in that war. We dropped massive amounts of napalm on them. They remember that.”

North Korea also remembered how its great nemesis Japan, seemingly invincible, was brought to its knees by a singularly powerful weapon wielded by the Americans. So the country started pouring its energies and limited resources into making a bomb of its own. Sometime in the late 1960s, Pyongyang received help from a Soviet Union anxious over China becoming the dominant communist power in Asia. It also struck secret deals with Pakistan for uranium and centrifuges. Now, what North Korea lacks in size and strength as a nuclear power it more than makes up in bravado and unpredictability.

Hough has seen this all before. He recalls 1982 and 1983 when then-President Ronald Reagan shocked the political establishment with statements that suggested war was imminent. And it reminds him of Cold War saber rattling between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. “The flare-ups we’ve had with North Korea in the last 15 years — it’s been mostly show,” Hough said. “Tensions spike, then things calm down.”

But one thing is very different this time around, he said — “North Korea’s increasing ability to project real force.” Coyle, the former Department of Defense testing director, agreed the threat grows, more as a looming danger than an immediate crisis. “However,” he warned, “time is not on our side.”