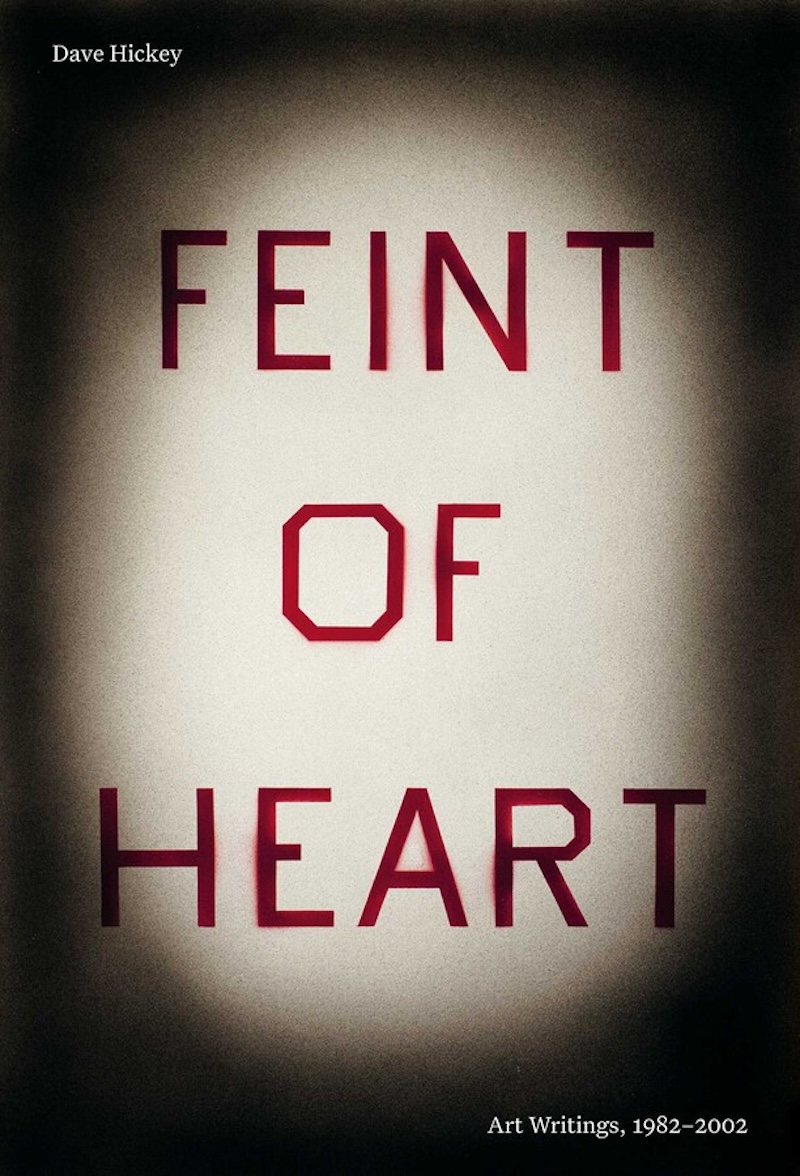

Book Review | ‘Feint of Heart: Art Writings, 1982-2002’ by Dave Hickey

Living Literature Disguised as Art Criticism

Like Greil Marcus writing about music, or Jed Perl and the late Peter Schjeldahl writing about art, Dave Hickey’s essays are interesting whether or not you’re interested in the artist or art he is discussing. As he says himself in a 1982 essay on Ed Ruscha, “criticism is not about art, it is only thinking ‘in the neighborhood of art.’” What Hickey is after, as editor Jarrett Earnest notes in Feint of Heart’s introduction, is “a mode of writing that replicates the experience of great art without reducing any of its power”; it is an effort “to craft living literature disguised as art criticism.”

The art Hickey was drawn to was eclectic and his opinions were clearly influenced by the fact that he lived and taught in Las Vegas, far from the art world of New York City, with its blandishments and demands. Hickey also wrote about music for Rolling Stone, and the lively style of a magazine journalist blends surprisingly well with the confidence of the professor who seems, casually, to know just about everything. Even the book’s title — a nod to a painting by Ruscha — suggests something of Hickey’s sense of ironic humor. His ideas and opinions are bold and boldly stated, so he’s hardly “faint of heart,” but his heart — that is, his affections and passions for the art he’s writing “in the neighborhood of” — is often given to “feints,” quick and deceptive rhetorical moves, as he elegantly gambols from one thought to another.

Hickey died in November of 2021, so the 20 essays in Feint of Heart — all written between 1982 and 2002, and mostly for exhibition catalogues — are from the first part of his career, what Earnest calls his “golden period,” when he was writing memorable books like The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty (1993) and Art Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy (1997). In keeping with Hickey’s catholic tastes, Feint of Heart covers artists both well- and lesser known.

Writing about the former, Hickey is cleverest and most contrarian when discussing the work of Norman Rockwell. Hickey points out that “The icons of a living culture do not begin as canonical works preserved in books and museums and taught in university classes. They begin as treasures of living memory.” For Hickey, Rockwell’s illustration for the May 25, 1957, cover of The Saturday Evening Post, entitled “After the Prom,” is such a treasure, one worth extensive analysis and evaluation. The image of a “soda jerk” sniffing the corsage of a young girl while her proud and innocent beau looks on may strike our jaded eyes as extremely sentimental, but Hickey remembers being a teenager in 1957 when “Rockwell’s prescient visual argument that ‘the kids are all right’ was far from de rigueur.” He concludes the essay by stating what he believes is the painting’s most pointed message: “democracy progresses in an untidy dance of disobedience and tolerance,” a hopeful thought for these times.

Rockwell’s reputation as a middle brow painter makes him an inviting subject for a renegade critic, but Hickey has something worthwhile to say about any artist he chooses to cover, whether it be Ruscha, Serra and Warhol, or Josiah McElheny, Sarah Charlesworth, and Hung Liu. Hickey is a Texan, both by birth and inclination, and among the most genial essays is a piece on Vernon Fisher, also of the Lone Star State. In one passage, Hickey writes: “Vernon and I indulge in a little West Texas bitching about people who don’t take care of their property, who neglect their animals and (worst of all!) don’t take care of their tools!” In a neighbor’s yard, Hickey notices “a rusting wire stretcher lying in the weeds next to a partially repaired fence” and remarks, “This is easily as annoying and upsetting as coming across a murder victim in a New York alley, especially since the wire stretcher’s not even broken.” Hyperbole? Sure, but like all Hickey’s writing, it’s in service of a larger point, in this case that both artist and critic would never treat their respective mediums with such disregard.

Ultimately, as Earnest points out, Hickey’s essays model “the various and sometimes conflicting ways which art comes to matter in our lives: why we might make it, look at it, and discuss it among our friends with the vigor that Dave does and proposes we should.” Indeed, while the book contains a nearly 50-page portfolio of mostly color images illustrating work by the artists under consideration, I found myself rarely turning to it. Partly, this was because Hickey’s descriptions of the art works are so creative and precise, but mostly it was because his prose is so vivid and entertaining, so full of unexpected connections between ideas and things. It’s a good sign for a writer (if less so for an artist) when, rather than looking at pictures, we would prefer to hear the critic talk about them.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.