Fight for Freedom:

The Chumash

Uprising

of 1824

Looking Back 200 Years After the

Largest Indigenous Revolt of the Mission Period

By Ryan P. Cruz | July 18, 2024

Two centuries ago, the Chumash people living in the mission system rose up against their Spanish and Mexican rulers, launching a coordinated uprising and taking over three strongholds — Mission La Purísima, Mission Santa Inés, and Mission Santa Barbara — in what became the largest organized rebellion of the mission period.

Over the course of four months — from February through June 1824 — the Chumash rebels fought with the Mexican military in several battles while Spanish friars attempted to negotiate the return of hundreds of Chumash who had fled from the missions inland to the mountains. The conflict highlighted the plight of the Chumash, who had been forced into a new culture, and the shaky political turmoil of the region, which was under fractured leadership after Mexico officially declared independence from Spain in 1821.

Though early records attribute the uprising to a singular event, the whipping of a Chumash boy by a soldier at La Purísima, historical research paints a more complex picture, one that explains the revolt as a fight for liberation, not revenge, against the years of inhumane treatment under Spanish and Mexican rule and the destruction of Chumash culture, particularly the suppression of its profound spiritual beliefs.

Setting the Scene

When Spanish missionaries landed on the shores of modern-day Santa Barbara in 1769, the Chumash population was estimated to be more than 20,000, with people living in hundreds of villages across the region. Over the next few decades, their numbers would be reduced to a few thousand, killed by the invading Spanish military, but mostly by the introduction of European diseases. Of those that survived, more than 85 percent were moved into the newly built missions, where they were converted to Catholicism.

In “Levantamiento!: The 1824 Chumash Uprising Reconsidered,” written by historian James Sandos and published in the Southern California Quarterly, Sandos writes how the mission system used a method of “complete immersion” for the indigenous peoples in new Spanish settlements — teaching European methods of agriculture and behavior and preaching a new religion.

Missionaries, believing they were saving souls through Christianity, enforced a completely different spiritual belief system in order to, as one Spaniard of that period wrote, “make them forget the ancient beliefs of paganism” and to “prepare them to take their place as lower-class citizens in Spanish society.”

This clash of cultures was profound. Chumash society was a basically peaceful one of hunter-gatherers and artisans, where men and women served equally as chiefs and shamans. It was a thriving network of tribes that lived in the region for thousands of years. They used their complex understanding of plants and sea life for medicine and food, studied the stars, navigated the waterways, and engaged in commerce by trading along the coast and with the island villages in their redwood-plank tomols. They saw little need for clothing, and they were far less sexually inhibited than their European counterparts. Their religious practices were robust — with ceremonial songs, dances, and music.

To the Franciscans, this society was very different from the hierarchical empires the Spanish conquistadors had found when they arrived on the South American continent. To the friars, the Chumash were lost souls in need of saving, and they vowed to stop at nothing to lead them to Christianity.

Recent historical research and writings have reflected on how this forced religious conversion, over time, took away the Chumash people’s sense of connection to their culture, to their ancestors, and to one another.

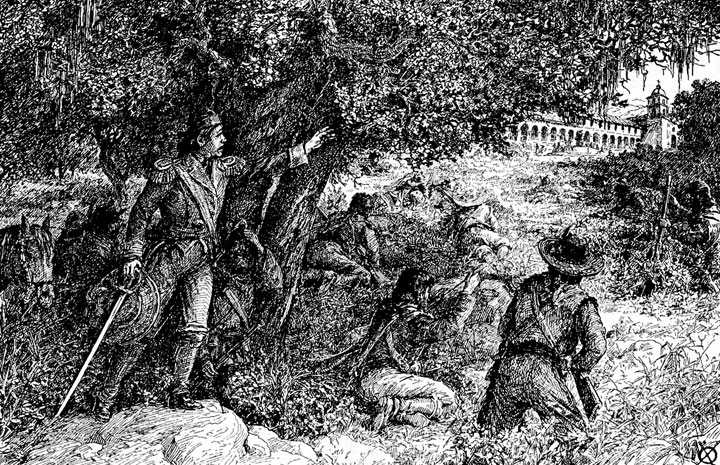

‘The presidio soldiers met the Chumash, now ready with bows, arrows, and the rifles from the mission guards. After three hours of fighting, according to Ripoll’s account, the soldiers retreated to the presidio and left the Chumash in possession of the mission.’

Breaking Bonds

Šmuwič-Chumash filmmaker Spenser Jaimes, who is researching a documentary he is producing about the revolt, thinks the entire story of the uprising is far more complex than the one based on documents left by priests and soldiers. “Sometimes just one side is represented,” Jaimes said. In fact, the Chumash at the time held varying opinions about the Spaniards and Catholicism.

By the time of the revolt, some Chumash people living in the missions were sincerely devout Catholics who had positive relationships with the friars. Others were less enthusiastic but felt they had no other options. Some, however, refused to convert and lived in villages tucked away from the Spanish settlements.

This fractured the Chumash way of life in ways that often go unmentioned in the military accounts of the revolt, Jaimes said. “It was such a huge part of life to have religion taken away….”

Sarah Koyo, an activist who has both Šmuwič-Chumash and Spanish heritage (as well as Irish and Tohono O’odham) emphasized the importance of acknowledging religion’s role as a tool of colonization. “It’s about breaking bonds — about breaking your connection to your land, breaking the connection to yourself,” Koyo said.

“It’s supposed to be about saving your soul, forgiving your sins,” she continued. “But there’s this whole other side that if you don’t, then you’re not going to be forgiven; you’re going to be punished.”

One of the most controversial methods the friars used at that time was confesionarios, or confession guides. They were intended to modify behavior, according to Sandos, “to elicit detailed information from Chumash confessants.”

Only two confesionarios have been found, one of them written by Fray Juan Cortés at the Santa Barbara Mission in December 1798. It showed how, by following the guide, priests were able to teach the commandments in both Spanish and Barbareño, while leading newly converted Chumash through a checklist of sins that would monitor who was “still practicing their native traditions or harboring un-Christian desires.”

By 1815, the questionnaire was specifically asking about shamans, cures, native medicines, and sexual behavior. Before long, the annual confessions, held between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday, became a point of intense contention among the mission Chumash.

Another method of breaking Chumash culture was keeping unmarried women under constant supervision to prevent traditionally open sexual practices. According to Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue, who visited the missions during this period, girls were kept in “dungeon-like rooms,” only allowed out for daily mass when they were “driven immediately into the church like a flock of sheep by an old ragged Spaniard armed with a stick.”

In the few Chumash villages that were able to survive outside the mission system, their spiritual beliefs were continually practiced. Accounts passed down orally through families suggest that a more mystical undercurrent, tied to Chumash religion, may have emboldened the uprising.

One story tells of a medicine woman who had a datura-induced vision years before the revolt, in which a Chumash goddess told her that they could renounce their baptisms and return to their old ways by “washing their hands in the tears of the sun” — a symbolic image that resonated with the Chumash.

Priests, when they heard that this vision was spreading throughout the missions, attempted to repudiate the dream. But it’s likely that the vision story was kept alive in the shadows by those Chumash who were increasingly unhappy.

Another sign from the stars, according to Sandos’s research, was a “large comet that became visible in the sky over southern California in December 1823 and persisted well into March 1824.” The comet held a significance in Chumash culture as a sign of “new beginnings,” Sandos said, and “may have provided the impetus to rise at that time.”

Political Turmoil and Pirate Threats

Meanwhile, political developments led the Spanish living in Santa Barbara to arm and train Chumash men in military strategy. In 1810, the Spanish colonial government in Mexico City stopped sending supply ships to the missions, leaving the priests and soldiers without pay or military provisions. Around 1818, Hippolyte Bouchard, a pirate from Buenos Aires, was marauding his way up the Alta California coast, threatening to wreak havoc on weakened Spanish settlements.

Father Antonio Ripoll, whose written account is the most detailed firsthand description of the revolt, had organized and trained an infantry of 180 Chumash fighters at Mission Santa Barbara: 100 archers reinforced by 50 more wielding machetes and a cavalry of 30 lancers. Ripoll even allowed the group to choose their corporals and sergeants. He called the force the “Compañía de Urbanos Realistas de Santa Bárbara.”

When Bouchard arrived in Santa Barbara, he razed the Ortega Family Rancho, near modern-day Gaviota, taking all the food and killing the livestock. When he set his sights on the Santa Barbara settlement, he was met by a cavalry of presidio soldiers and the newly trained Chumash force, who together defended the mission and the Santa Barbara pueblo, sending Bouchard back to his ship.

Priests at La Purísima organized a similar Chumash infantry, encouraged by the success of Ripoll’s company. These efforts taught the Chumash fighters European military tactics, from group movement to weapons training. Prior to colonization, Chumash people hunted and fought in small bands, but with the new training, the men learned how to mass and drill in larger movements. These skills gave the Chumash a “new sense of power and the awareness of large-group, collective action.”

In the missions, the Chumash toiled in the fields, cooked the food, built the structures, and provided all the labor and resources for both the priests and the presidio soldiers. When fresh supplies were halted, the settlement needed to be even more self-reliant, and the work increased dramatically for the mission Chumash.

In 1821, Mexico declared independence from Spain, sending the Alta California region spiraling into more chaos. The secularized Mexican government declared that all indigenous peoples were to be treated as civilians, regardless of their faith, but this new law did little to help the Chumash. In fact, now that the mission friars were no longer connected to, nor especially protected by, the new secular government, some soldiers felt free to take more aggressive actions against the mission Chumash, and the priests frequently had trouble protecting them.

With the mission settlements more vulnerable than ever, the priests tightened the cultural noose on the Chumash from 1820 to 1824, leaning even harder on the use of annual confessions to break bonds with Chumash traditional beliefs. Whispers of a coming uprising spread at the missions.

The Last Straw

The two surviving Chumash accounts of the revolt, an interview with Maria Solares and another with Luisa Ygnacio (daughter-in-law of Maria Ygnacio, and great-grandmother of Barbareño Chumash historian Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto), both conducted by ethnographer and linguist JP Harrington, refer to a rumor started by a sacristan at Santa Inés that deepened the sense of paranoia on both sides.

The sacristan, according to the accounts, told the mission Chumash there that the priests planned on killing them during the next Sunday Mass. The same sacristan then told the priests that the Chumash were planning on shooting them with arrows. This rumor was not included in Spanish or military accounts of events.

Dr. John Johnson, Curator Emeritus of Anthropology at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and a scholar who has studied the revolt for decades, spoke about the differing accounts during a lecture he gave in June at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

He described the accounts of the uprising as having the “Rashomon effect,” after the Akira Kurosawa film of that name — how one event could be told from several points of view, each with different, often conflicting, details.

“I think this is what we’re seeing in the Chumash uprising,” Johnson said.

But even differing accounts of the revolt have enough corroborating details to determine a generally accepted order of events starting on February 21, 1824.

On that day, a Chumash boy from La Purísima was visiting a relative being held prisoner at Mission Santa Inés. For unknown reasons, a soldier stationed there, Valentín Cota, ordered that the boy be beaten. While this punishment wasn’t out of the ordinary, it was the last straw for the Chumash — who considered these actions unacceptably brutal.

Father Ripoll, whose accounts describe the Chumash plight with empathy, expressed shame when recounting the behavior of the soldiers.

“Who gave the power to Corporal Cota to render such despotic punishment … ?” Ripoll asked. “Why are the complaints of these unfortunate people [and] made by the fathers on their behalf, not heard? And why that show of disdain when such complaints are made?”

The Uprising Begins

More than 500 Chumash stormed Mission Santa Inés alongside men from neighboring villages. They shot arrows at the soldiers and set fire to the buildings. After hours of battle, the Chumash took control of the mission. Soldiers and a priest barricaded themselves in a building.

The next day, a group of Mexican soldiers returned to flush out the Chumash by setting fire to their quarters. Four Chumash men and 15 women and children were killed either in battle or the fire, along with one Mexican soldier.

The rebels retreated to La Purísima, where the revolution’s supporters had grown to more than 700. They took over the property and prepared for the arrival of Mexican army reinforcements by cutting slits for weapons in the adobe walls and rolling the ceremonial cannons. They would have to wait nearly a month for the Mexican reinforcements.

One Chumash man was killed during the battle, and the rebels killed four Californio settlers who were passing through the area.

Battle at Santa Barbara

At Mission Santa Barbara, a messenger from the northern missions arrived asking for help. Father Ripoll described the events in great detail in a letter to the president of the missions.

Ripoll’s first course of action was to rush over to the presidio, where the military was stationed, and ask Commandant José Antonio de la Guerra to order the guards at the mission to stand down because the Chumash neophytes were preparing to join the revolt. Though the commandant agreed to write the order, he refused to accompany Ripoll back to the mission as a show of peace.

On Ripoll’s return to the mission, he found nearly 400 Chumash fighters armed with bows, arrows, and machetes. The group had been informed, falsely, he wrote, that the soldiers were planning to kill them all the next day as punishment for the violence at Santa Inés and La Purísima.

The priest attempted to talk the group down, showing the order issued for the three guards to stand down and leave the mission. But tensions were high, and when Ripoll and the armed Chumash walked over to the soldiers’ quarters to deliver the message, some of the rebels demanded the soldiers leave their weapons. Two of the guards refused, and Chumash men grabbed the muskets from them. In the skirmish, the two soldiers were cut by machetes. They returned to the presidio with Ripoll, where, when the commander saw what had happened, he ordered troops to the mission as a show of force.

The presidio soldiers met the Chumash, now ready with bows, arrows, and the rifles from the mission guards. After three hours of fighting, according to Ripoll’s account, the soldiers retreated to the presidio and left the Chumash in possession of the mission.

On the first day at Santa Barbara, four soldiers were wounded with arrows; three Chumash were killed, and three were wounded.

A Chumash Exodus

Expecting an aggressive response, the Chumash prepared their escape. A small group stayed to fight, while the rest — men, women, and children — were escorted into the hills, taking provisions from the mission’s storehouse, but leaving their quarters locked and undisturbed.

Presidio soldiers returned to the mission several times, killing four uninvolved Chumash who were in the area. Ripoll recounts one of the killings, in which the innocent man pleaded not to be taken to the presidio. “But even these words were of no avail,” Ripoll writes. “With a single bullet they brought him down dead.”

Again, Ripoll shares his distress at seeing how the soldiers had ransacked the Chumash quarters and priests’ rooms. “This was the havoc that drove the nail into my already afflicted heart,” Ripoll wrote. “What destruction! All the doors were broken open, boxes, beds, clothing, grain, all were stolen. And what they could not carry away, they cast out along the road.”

During that first week, Chumash refugees hid a few miles outside of town near San Roque Canyon. Father Ripoll sent messages back and forth, asking them to consider returning, promising they would not be punished. But hearing that the soldiers destroyed their belongings at the mission, they did not trust it would be safe and told Ripoll they planned on staying “in the open country” and living off the land.

They fled deeper inland toward the San Joaquin Valley, where they settled among friendly Yokuts on a swampy island in Buena Vista Lake.

A smaller group of 50 Chumash piled into two tomols kept near Goleta, braving the choppy late February seas and making the 30-mile crossing to Limuw (Santa Cruz Island).

The End of the Revolt

Over the next few months, the newly appointed Governor of Alta California Luis Antonio Argüello organized two military expeditions to return the Chumash that had fled from Santa Barbara, and to recapture La Purísima, which the rebels had held for nearly a month.

On March 16, a Mexican military force of 109 soldiers stormed La Purísima, engaging more than 400 Chumash fighters in a three-hour battle. After the Chumash suffered 16 killed and many wounded, they negotiated a surrender. According to military records, the army seized two cannons, 16 muskets, 150 lances, six machetes, and an “incalculable number of bows and arrows.” The Mexican army recorded one death.

Seven captured rebels were condemned to death for the killing of four soldiers. Eight more were imprisoned at the presidio for eight years, while four ringleaders were sentenced to exile in Monterey — including the charismatic leader, José Pacomio Poqui (An ironic historic fact: Years later, Poqui became a Monterey city councilmember and police commissioner).

Father Ripoll appealed to Governor Argüello on behalf of the Chumash, arguing that Mexico’s constitution made them equal in the eyes of the law. What finally earned the pardon, though, was the church’s view that natives were “children” under the care of the priests.

The first expedition to capture the refugees ended in failure. A detachment of 85 Mexican soldiers trekked into the mountains in April, but only encountered a group of non-mission Chumash. After taking one prisoner and killing him, the soldiers were hit by an unexpected storm and sent back home.

A second expedition was ordered consisting of 50 men from San Miguel and 63 from Santa Barbara (including Father Ripoll, who had refused to go along on the earlier expedition, and Father Vincent Sarria, both sent to help mediate). The division met up at San Emigdio in June, and met with the refugee representatives near Lake Buena Vista.

During three days of meetings, Father Ripoll and Father Sarria worked to convince the Chumash to return to the mission. In the months since they fled, the crops were failing, and though the Chumash were in a safe haven with the Yokuts, the hundreds of extra mouths to feed were causing a strain on the small village, which typically held fewer than 50 people.

The exact terms of the negotiations are unknown, but historians generally agree that the Chumash accepted the governor’s pardon.

All told, during the four-month revolt, 43 Chumash and eight Spaniards and Mexicans, known as Californios, were killed.

Little is known of what happened upon their return on June 28, though historical records say that about half of the refugees chose not to return to Mission life. According to the journals of a fur trapper nearly 10 years after the revolt, a community of more than 700 former mission Chumash were hidden deep in Kern County, living in a neo-native and European-style culture, combining the farming methods learned from Spaniards with traditional Chumash culture.

But that account is the last known record of these Mission escapees. In the early 1830s, a malaria outbreak swept through the San Joaquin Valley, killing most of the indigenous populations. (When the government, by then an American one, took an official count in the area in 1850, the Chumash group was not mentioned.)

By 1833, the Mexican government ordered that all the missions be secularized, ending the mission period in California. By then, the number of mission-registered Chumash had fallen to 2,788. Some mission land was turned over to the government, while much of the ranch land came into the hands of the Californios, ushering in a whole new era that would define what we know of modern-day Santa Barbara.

You must be logged in to post a comment.