Adding Insult to Injury: Radioactive Waste and DDT Rub Elbows off Coast of Los Angeles

UCSB Scientist David Valentine Releases New Study Pointing to Disposal of Radioactive Waste in Pacific Ocean

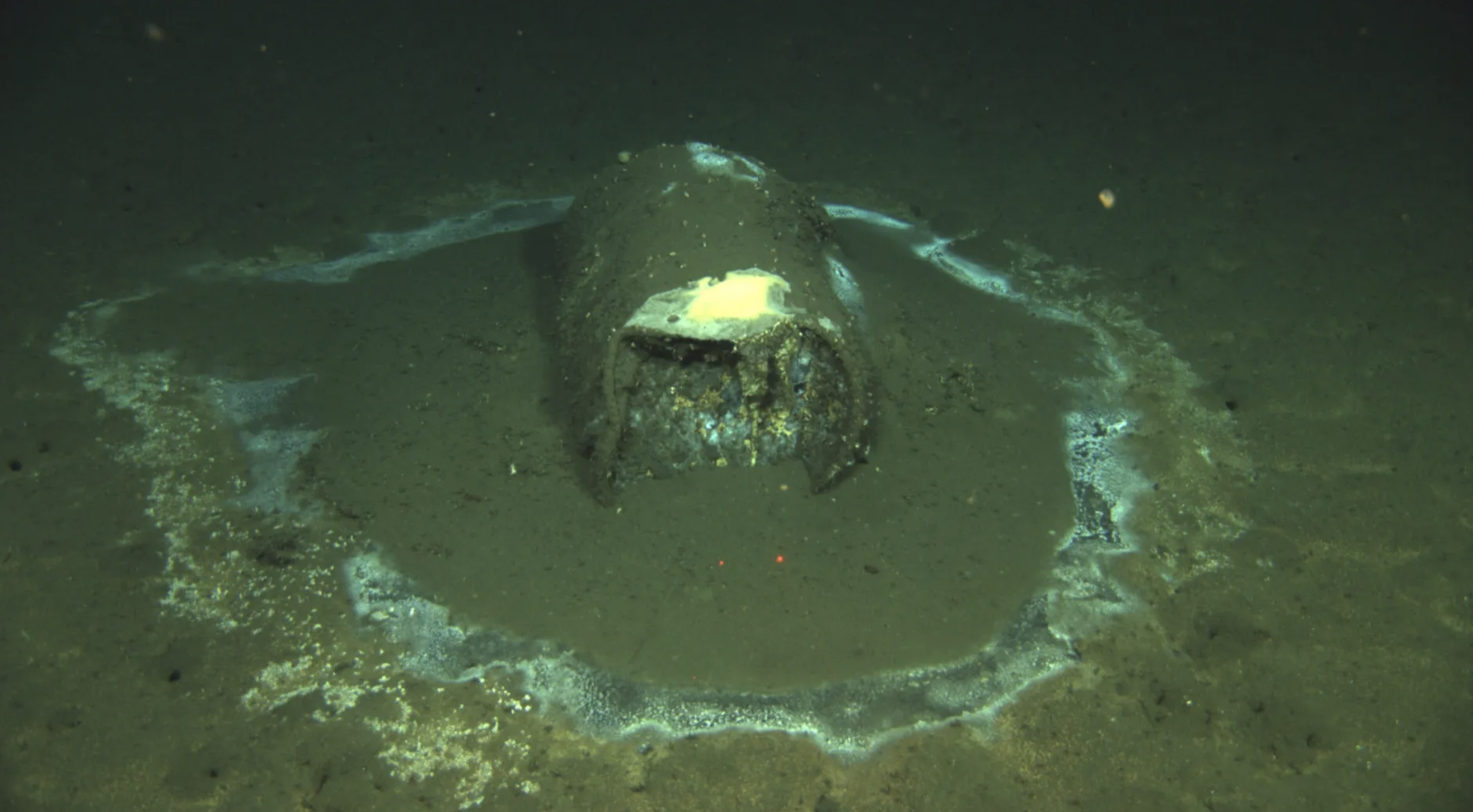

When UC Santa Barbara scientist David Valentine found an underwater graveyard of strange barrels off the Southern California coast between Los Angeles and Catalina Island, their contents were a mystery. Nailing down what was inside the barrels was not as consequential as studying what was found around them: shocking amounts of toxic DDT.

However, it was later revealed that the DDT waste itself — created by what was once the nation’s largest DDT manufacturer, L.A. County–based Montrose Chemical Corporation — was not contained in barrels. Instead, the harmful chemicals were pumped straight into the water.

A horrible discovery, yes, but it raised the question: If it’s not DDT, then what’s in the barrels?

According to a recent study by Valentine and his team in Environmental Science and Technology, it’s very likely that the barrels were actually full of low-level radioactive waste.

Records show that many hospitals, labs, and other facilities would sometimes dump barrels of tritium, carbon-14, and other similar waste into the sea from the 1940s through the 1960s, before the enactment of ocean dumping regulations.

Jacob Schmidt, lead author of the study and a PhD candidate in Valentine’s lab, dug up a paper trail of old records that pointed to California Salvage, the same company that Montrose hired to pour its DDT waste into the Pacific, being guilty of radioactive barrel disposal as well.

These records show that Cal Salvage received a permit in 1959 to dispose of radioactive waste in the ocean. Although Cal Salvage never activated that permit, records also recount how the now-defunct company advertised its radioactive waste disposal services and led a five-year operation of radioisotope disposal for multiple facilities around L.A.

Valentine believes Cal Salvage never activated the permit because it would have required the company to dump 150 miles offshore — a multi-day trip.

But, he said, if you just go out for a “morning jaunt” between the mainland and Catalina Island, you’re back in time for a siesta. Seeing how irresponsible offshore DDT disposal was at the time, it would be unsurprising if the company took shortcuts for other hazardous waste and dumped it closer to shore, too.

“That was their business model,” Valentine explained. “They took barges offshore with chemical waste and pumped the chemical waste into the ocean. So, you know, why not take some barrels with you and dump them while you’re out there?”

While the radioactive waste is bad, the DDT — a cancer-causing chemical that is essentially liquefying the insides of California sea lions — is worse, according to Valentine.

“We now have this added insult: Not only were we dumping massive amounts of DDT waste, but you know, let’s just throw some pearls of radioactive waste on top of that,” Valentine said. “But the DDT waste is the much more harmful of the two, because it works its way into the ecosystem. It biomagnifies. It concentrates.”

Unlike DDT, known as a “forever chemical,” the low-level radioisotopes like tritium that were being disposed of here have a shorter lifetime and would have decayed over the years.

“From what we can tell, these were ones that were used in research and industrially — so this isn’t the really nasty nuclear stuff,” Valentine explained. “It’s not that they can’t cause problems. But we don’t think they hold the same potential to cause problems as the DDT dumped down there.”

The DDT, on the other hand, covers a swath of seafloor larger than the City of San Francisco. And it has remained in its most harmful form, undegraded, almost 80 years later.

It’s all a part of a bigger, badder picture. Since the DDT discovery in 2011, researchers have continued to unfold an alarming legacy of toxic junk littered across the seafloor.

While surveying the barrels, researchers from UC San Diego recently stumbled upon a multitude of discarded military explosives from the World War II era. And as it turns out, there were 13 other areas off the Southern California coast that were approved for chemical waste disposal — including three million metric tons of petroleum waste — from the 1930s to the 1970s, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“We also know about maybe 60 whale carcasses that are down there,” Valentine added. “We still don’t fully understand what’s really going on down there. We don’t even have a map of where all this stuff is. So it’s really hard to think about solutions without even knowing the full scope.”

Mapping is in progress, with Valentine’s recent study contributing more concrete data as to the when, where, and how of the dumping. Valentine estimates that within the next year they’ll have more information about the extent of the “chemical stories” on the ocean floor.

But there may be hope. Valentine’s team is also studying microorganisms, and whether they have the potential to alter or degrade some of the petrochemical compounds lingering off the coast.

Additionally, politicians are really starting to pay attention.

This week, Rep. Salud Carbajal (D–Santa Barbara), along with 23 other members of Congress, signed a letter urging the Biden administration to dedicate long-term funding to the study and remediation of the issue — adding to the millions of dollars contributed by the state and federal government thus far.

“While DDT was banned more than 50 years ago, we still have only a murky picture of its potential impacts to human health, national security and ocean ecosystems,” the letter reads. “We encourage the administration to think about the next 50 years, creating a long-term national plan within EPA and [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] to address this toxic legacy off the coast of our communities.”

Premier Events

Fri, Nov 22

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Antique & Vintage Show & Sale

Fri, Nov 22

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Introduction to Crochet Workshop

Fri, Nov 22

7:30 PM

Carpinteria

Rod Stewart VS. Rolling Stones Tribute Show

Fri, Nov 22

9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Numbskull Presents: Jakob’s Castle

Sat, Nov 23

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Antique & Vintage Show & Sale

Sat, Nov 23

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Fall 2024 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Nov 23

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBCC Theatre Arts Department presents “Mrs. Bob Cratchit’s Wild Christmas Binge”

Sun, Nov 24

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Antique & Vintage Show & Sale

Sun, Nov 24

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

¡Viva el Arte de Santa Bárbara! Mariachi Garibaldi de Jaime Cuellar

Sun, Dec 01

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Tree Lighting Ceremony

Fri, Nov 22 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Antique & Vintage Show & Sale

Fri, Nov 22 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Introduction to Crochet Workshop

Fri, Nov 22 7:30 PM

Carpinteria

Rod Stewart VS. Rolling Stones Tribute Show

Fri, Nov 22 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Numbskull Presents: Jakob’s Castle

Sat, Nov 23 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Antique & Vintage Show & Sale

Sat, Nov 23 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Fall 2024 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Nov 23 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBCC Theatre Arts Department presents “Mrs. Bob Cratchit’s Wild Christmas Binge”

Sun, Nov 24 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Antique & Vintage Show & Sale

Sun, Nov 24 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

¡Viva el Arte de Santa Bárbara! Mariachi Garibaldi de Jaime Cuellar

Sun, Dec 01 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.