View from the Arctic:

A Journey Through the Ice,

from Svalbard,

to East Greenland

Exploring the World of Ice

at the Crossroads of Climate Change

By Mary Heebner | Photos by Macduff Everton

August 27, 2023

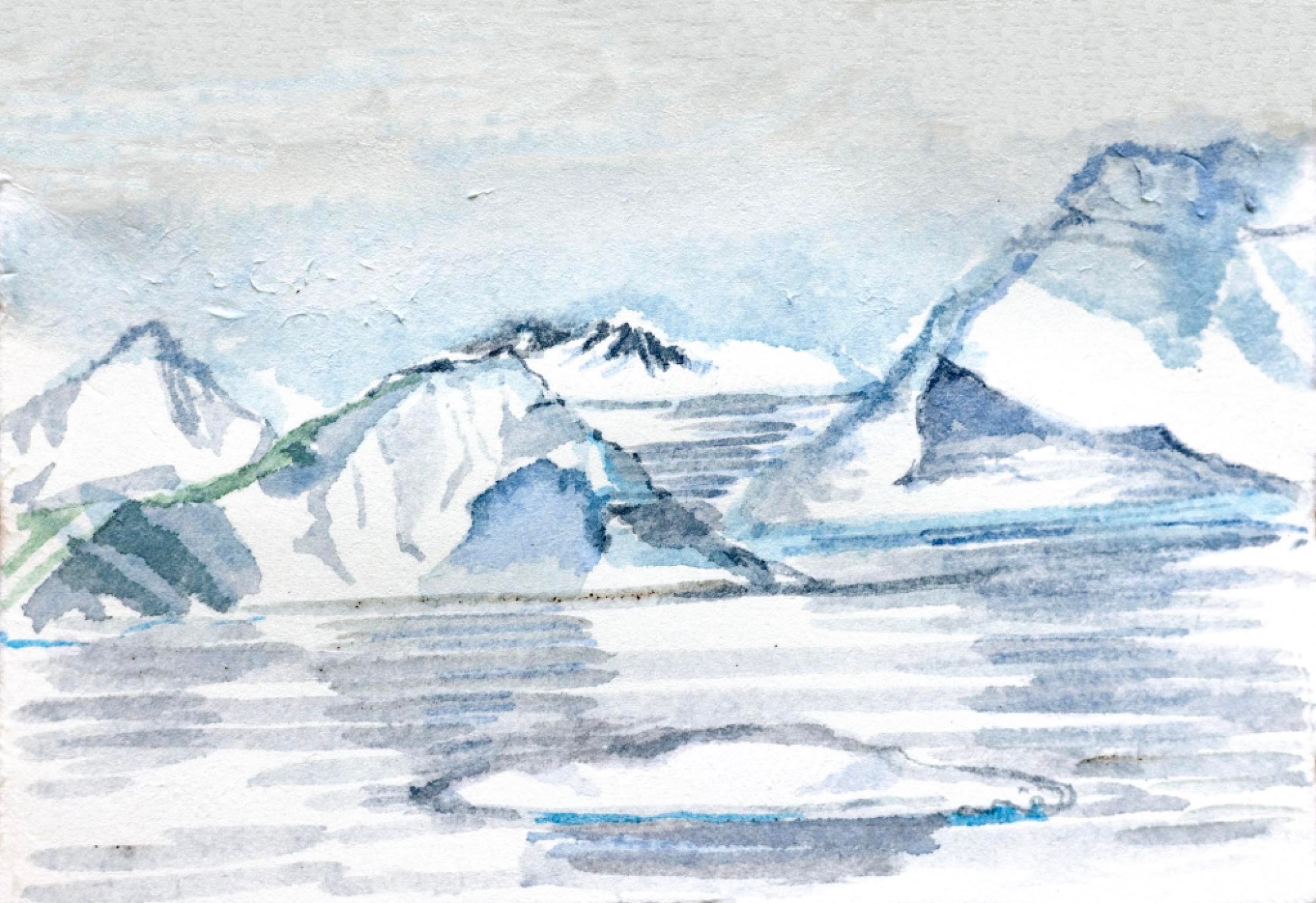

I am immersed in a landscape of astonishing beauty, summer’s enduring effulgent light. Striated fingers of land reflect on continuous open stretches of water, or polynyas, where mists of sea smoke insulate the water from freezing over. I feel a profound sense of the sublime; fierce and awesome. Small beings set against the perfect reflection of earth and earth’s illusion mirrored in the polished sea. The Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic is like witnessing the fearful symmetry of God.

We’re headed to the “Cold Coast,” the Old Norse name for Svalbard. A charter flight takes our group of 68 guests from Oslo to Spitsbergen, the largest of nine islands in the archipelago, where we’ll board the National Geographic Resolution, an ice-class Polar Class 5 vessel. From my window seat, peaks of the island protrude from a white frosting of snow cover; graphic, fantastic. I imagine my fingers pressing on soft porcelain-white clay, making depressions, wiggling my hand to create wrinkles in the frosted surface, pouring black paint down slopes creating bold, striated patterns. Wind pillows my parka, as I deplane in Longyearbyen, eager to board the ship and explore the fjords, glacial tongues, and catch sight of some wildlife. We are at 74 degrees North, just 650 miles from the Pole. We are closer to the North Pole, than the Arctic Circle. Pinch me!

[Click to enlarge]

Our first stop is a bus ride away; the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, built as an insurance against climate change, wars and natural disasters. This sets the tone for our journey. We are at a serious crossroads. Genetic diversity is diminishing, microclimates are rapidly shifting, entire ways of life — with the risk of extinction looming over one million species of plants and animals, according to a recent United Nations report — will either adapt, migrate, or die out. It is here, carved into the hillside above the airport, that seed samples from over 6,000 species of crops from around the world create an agricultural safeguard for future generations. There are over 1,800 genebanks in over 100 countries, housing collections of over 7.5 million seed samples. This June alone the Svalbard Global Seed Vault welcomed 40,507 new seeds from nine genebank depositors. In 2012, as the conflict in Syria escalated, the ICARDA (International Centre for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas) genebank safely, over five years, removed the Syrian seed store to the Svalbard Vault where they were duplicated, germinated successfully, and sent on to establish new genebanks in Lebanon and Morocco.

Climbing up the steep gangplank of the NG Resolution, the newly built 408-foot ship is small compared with most cruise ships, enabling it to ply waters inaccessible to many. Standing on the terrace off of our stateroom, the view is a Rothko painting in tonal greys, a pearl bright light kisses the horizon. We rush to the bow to take in the view. Small white spots are sighted on the port side of the ship, ten snow-white beluga whales break the lightly waffled sea, like a dream that surfaces from the unconscious, the illusive sea canary, surfacing in a coal black sea.

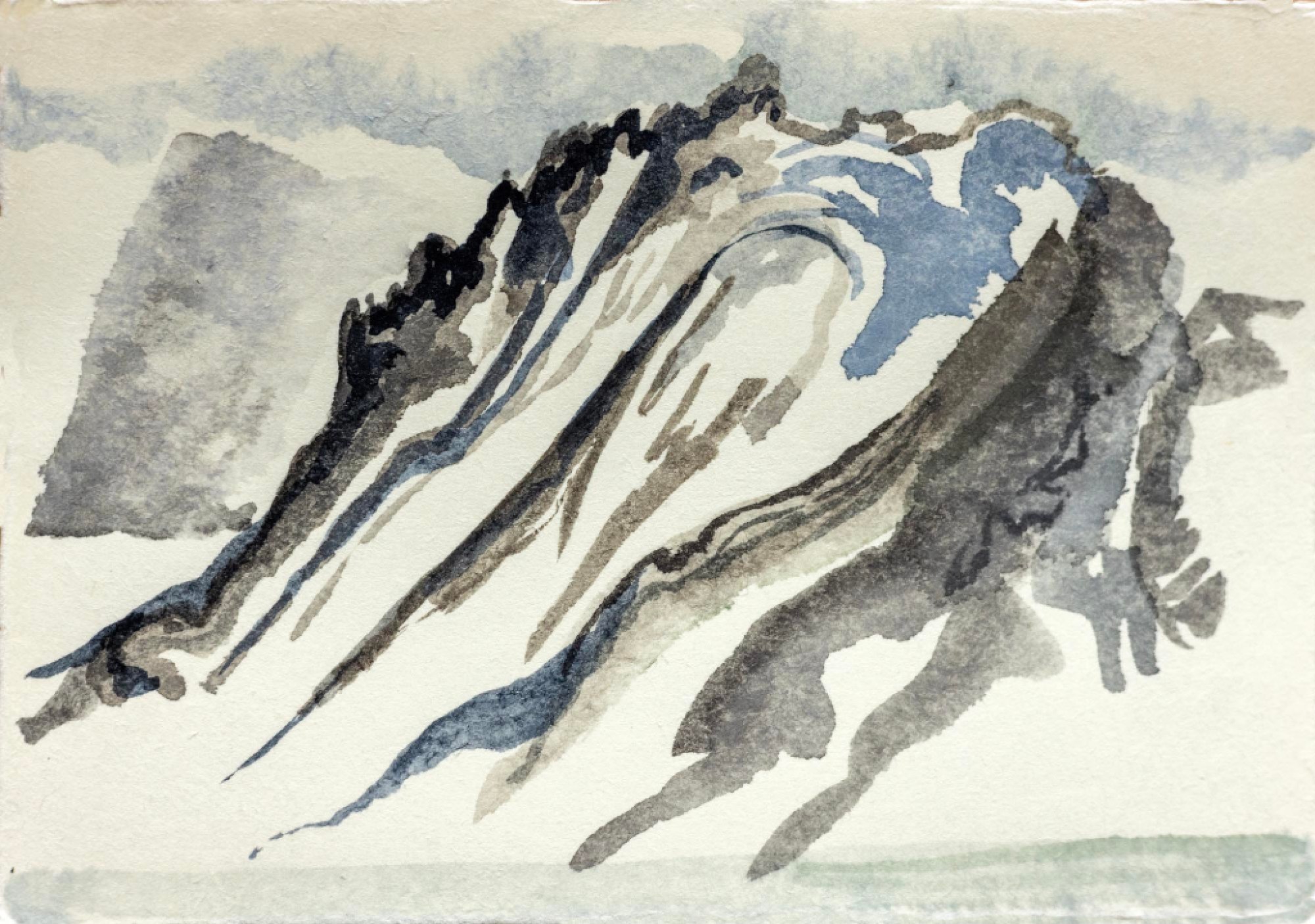

Svalbard’s taffy-like folds and faults create mountains of steep, black earth, deeply fingered with fjords, and streaked with remnant white snowfields. Graphic, stunning, the striking monochrome patterns reflected in a calm ocean resemble ikat patterns, or matrix QR codes. I sit at a table on the small terrace outside our stateroom at 4 p.m. making watercolors of the scene, but in just 15 minutes my face feels unreasonably hot. I realize that although my hatted head is bowed over the watercolor, the white of the paper reflects the sun’s rays back on my face and sears my cheeks crimson. The sun is that intense. Sun is white hot, is a fire, is close and fierce.

Writer and Arctic explorer Gretel Ehrlich says, “The Arctic is the Earth’s air conditioner. The Arctic drives the climate of the whole world.” In her book, This Cold Heaven, Ehrlich cites an Inuit word, sila. Sila translates as weather, but this word seems to also mean the weather we carry within us, and perhaps, consciousness of self, and of our place in the world. What is the weather I bring to this journey? How will this journey change the ways I understand my place in the world?

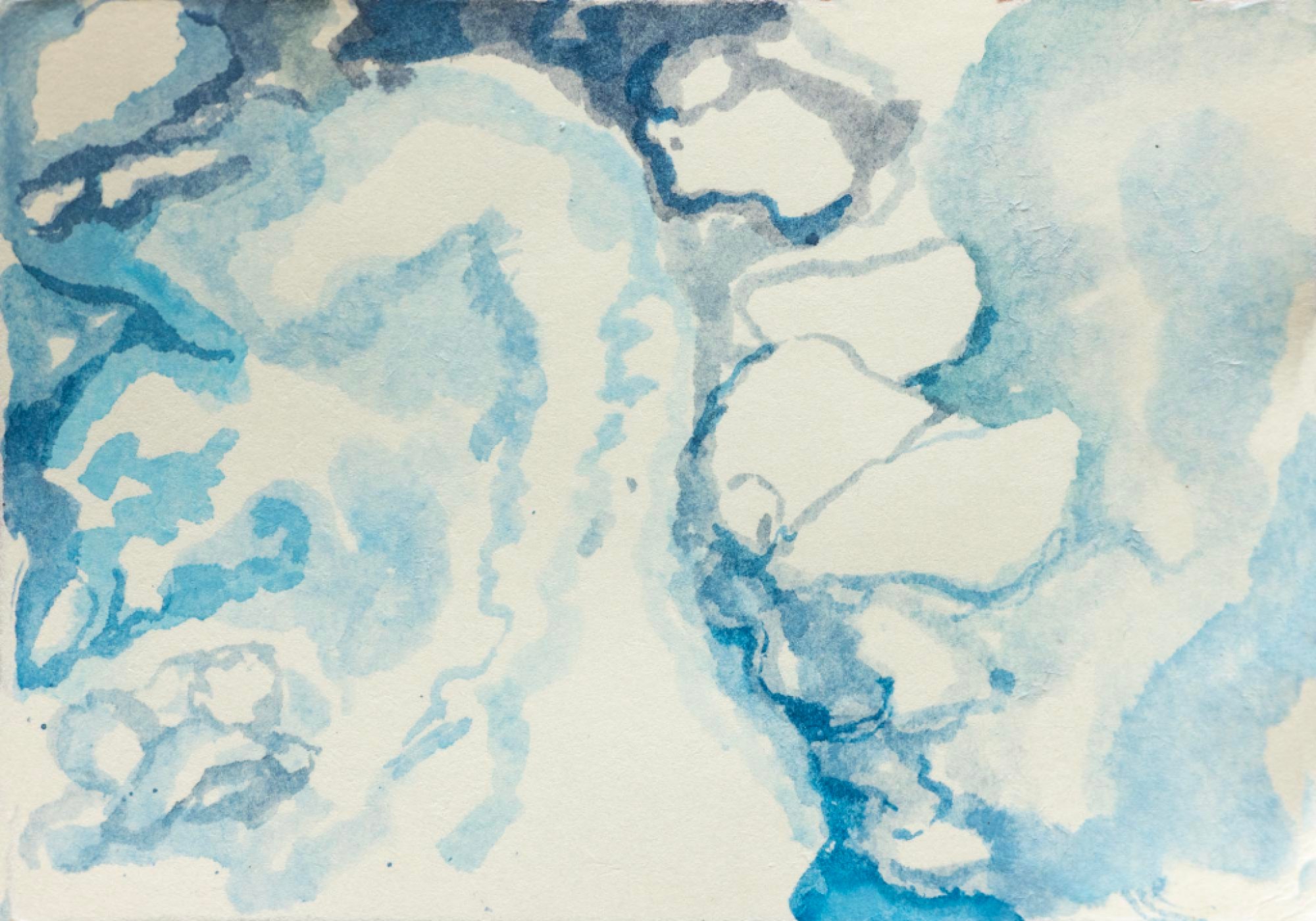

Sailing above the Arctic Circle at day’s end, the sun is fixed overhead, an unwavering white light, no rosy hues to bracket a day. A world shaved down to the essential tonalities of black and white. High-frequency waves of blue are at play in the ice fields, exploding in hues from violet-indigo to ultramarine, cerulean and turquoise. Celestial colors. Sky god robes. No other color finds purchase in this world of ice, rock, and lambent light. Around midnight the air seems dipped entirely in a vat of blue dye. Blue is the shortest wavelength in the visible spectrum, to me, the color of distance and longing — wild blue yonder. My lungs fill and empty of blue air.

The poles are the elemental, chemical, essential extremes of Earth, long days of darkness then long days of daylight, expressed most dramatically at the solstices. In a perpetual dance of Earth, Air, Fire, Water, the Poles lay bare a delicate balance. Ice shields the Arctic from the sun’s fiercest rays, by reflecting them back into the atmosphere. Primordial sky-water was married to rock as ice for thousands of years, and in the Arctic, the ice sheet deflected 80 percent of the sun’s radiant energy. And this is what is changing. The Arctic and Antarctic deserts are the final vestiges of the last Ice Age. The Poles are cold, dry deserts, with snow dunes, and flat plains of ice covering silty, heavy, salty soils that leach into the water, making the adjacent ocean super-salty. For years, the high Arctic desert garnered only two to three inches of rain a year, but now it is beaten by rainstorms, wind-driven waves crumple up new ice in its fists, permafrost is melting, and floods gnaw at the edges of land. The temperature differences between the North Pole and the Equator affect wind velocity, wind-fueled wildfire, heat waves, and storm activity worldwide.

Arctic light is clear as glass or clothed in a dense wool of fog. As the climate warms, ice caps melt, sea fog increases, and massive amounts of freshwater from melting glaciers flood into the sea, affecting its salinity. The land, now disburdened by weighty ice rises up, while the ocean, taking on more liquid, makes sea level rise.

I describe the Arctic as vast vistas of black and white. Even the birds are feathered in black and white. But are they? This is a human-centric vision. Most birds and insects are tetra-chromatic, meaning their retina contains four separate higher intensity light receptors, so they can see non-spectral colors such as ultraviolet reds, greens, yellows, and purples. We see white when all our retinal cone cells are equally stimulated. A bird sees non-spectral color, their white feathers reflect ultraviolet light. Imagine what polychromatic splendor birds see when flitting about, diving, hunting, and nesting. So much depends upon the eye of the beholder.

Then comes the fog. With climate change, a dark, ice-free ocean is absorbing more solar radiation, so that water underneath the sea ice is just enough warmer than the surrounding air that the ice melts, and that in turn causes further warming. Researchers describe this feedback loop as Arctic amplification. The ice in the Barents Sea between West Svalbard and the northern cape of Norway is melting at a rate not twice but seven times faster than the global average. As the ice melts this warmer water pushes against the colder air condensing into a soupy fog. As sea fog increases, both the visibility for and of vessels that traverse these waters can be perilous. Our ship sails guardedly through thick white clouds. Although it is perpetually daytime, the fog obscures the hard sun, but also everything else. Little islands of ice vanish into whiteness.

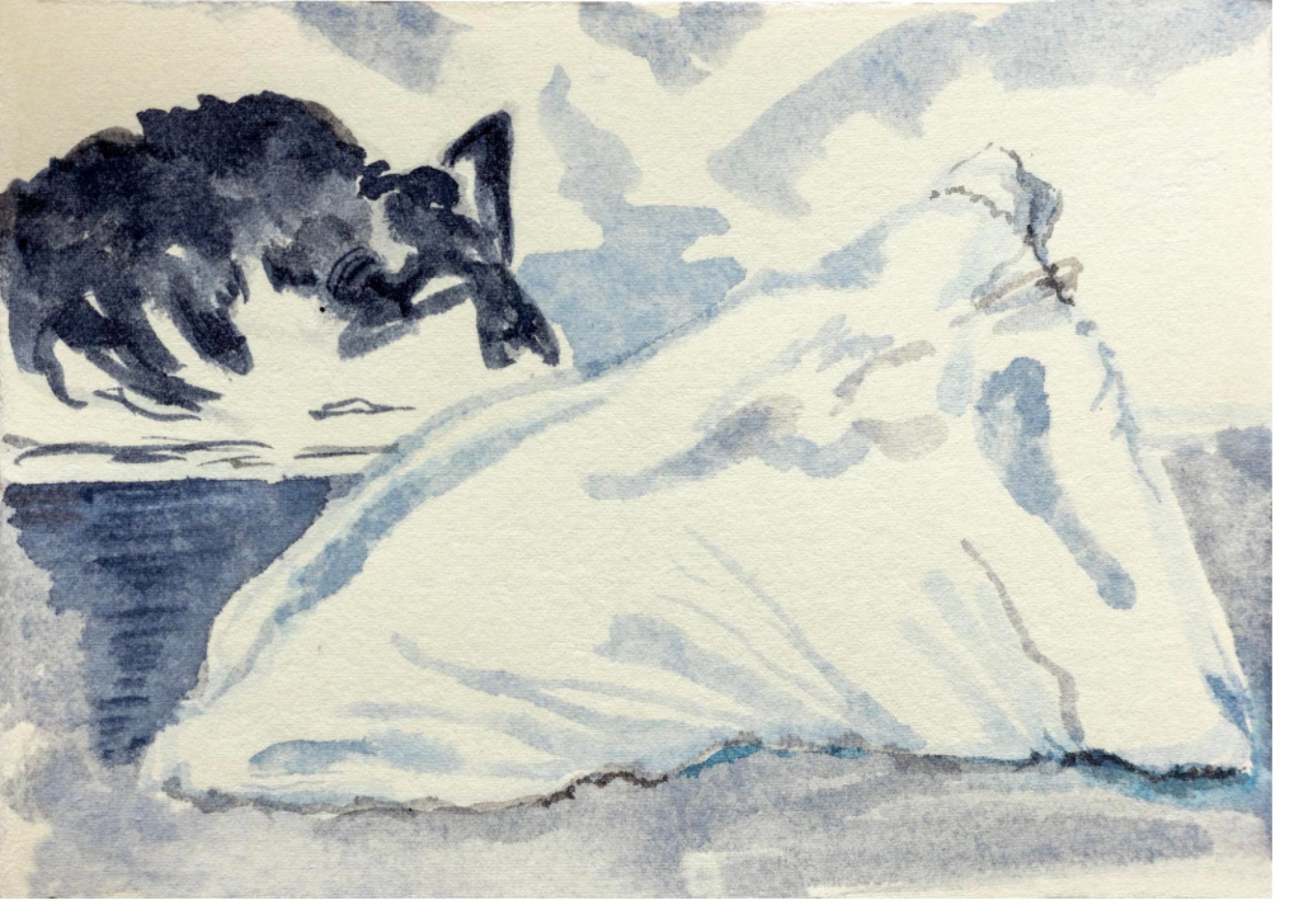

The sea, ice, cloud, and land, this world of pattern, and reflection, confounds my senses. It sings to me. But it’s the bear that grabs the focus of the group; everyone wants to see a bear. Distant shapes, dots of ivory white on snow white, a polar bear, perhaps mother and a cub, traverse the sea ice. Looking for a white bear on white ice in a white fog – what could be easier? A polar bear’s thick hairs are translucent and hollow, reflecting the sun’s white light, while their skin is a heat-absorbing black. Kerstin, a staff naturalist explains at that night’s recap that females mate in April–May but are able to biologically delay implantation until September-October. The mother digs a den in deep south-facing snow drifts, near the coast. Kerstin shows an image of twins, hairless, pink, one-to-two-pound fragile beings, that are born after an eight-month gestation. The mother and cubs leave the den ending their confinement of two months, wobbly, furry fluff balls, learning from their mother how to hunt and survive. Then, each 300-pound yearling must make it alone, as the mother goes off to hunt, and mate again. Expert swimmers, with semi-webbed paws to paddle, a polar bear is basically a marine mammal whose habitat is sea and ice. As its habitat and food sources diminish, a female may only have enough fat to birth a sole cub, if that.

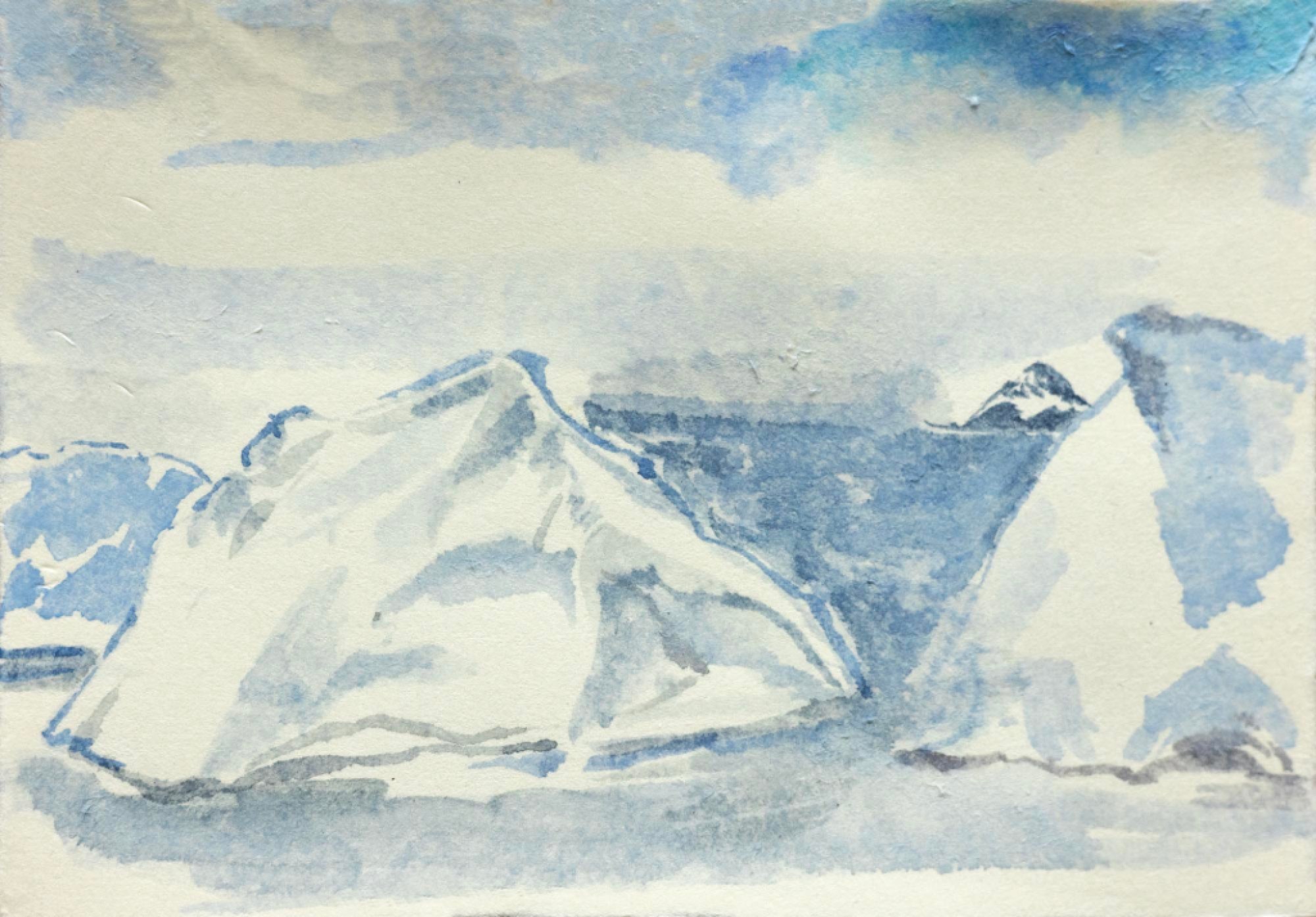

One evening when the fog lifts, I see land on the horizon. But it’s a trick of the eye, a mirage, a fata Morgana, named after the sorceress of Arthurian legend. A layer of heated air wraps around a slightly cooler ocean surface causing the light to bend at the horizon, conjuring the illusion of barges, castles, islands. The ship cuts through stretches of ice-clotted waters; triangle, rhomboid, square, and oblong, all manner of ice, some thinning enough to capture a jewel-like sapphire light. A gash of powdery blue skyline reveals the seam where sea and sky meet, but it is above where I truly believed the horizon line to be. In moments, this wound heals into a seamless horizonless expanse. Illusion abounds.

Jackie, a staff naturalist with a penchant for plants, leads our party ashore at Hornsund, the southernmost fjord on the west side of Spitsbergen Island and we walk ashore in a tight group. She is required to carry a rifle as a precaution, in case of a bear encounter, aware that we are the interlopers on their land. Picking across rounded granitic stones, she points out earth-hued lichen and spongy tundra and mosses that creep by millimeters ever so subtly, rootlessly, across land’s surface. Bonsai-canopies and understory offer enough cushion for reindeer to graze. Quietly, we approach a pair of grazing reindeer, their coats shaggy, molting in this season of light. Insects pollinate five-petaled clusters of violet saxifrage. The place is abuzz with life. Just before loading into Zodiacs to return to the ship, Macduff (my photographer husband) shows me a photo he shot of a wet footprint larger than my face, signs that a polar bear had walked here recently. Above us, tens of thousands of chattering red-legged kittiwake, auklets, and guillemot make nest in the sheer jagged rock face. As we leave, I see a flush of white birds above me — a starry constellation against a cloudless, ultramarine sky.

[Click to enlarge]

Sailing south westerly from Spitsbergen, we island hop our way toward East Greenland, then across the Denmark Strait to end our journey in Iceland. We will cover 2,578 miles on this trip, about the distance from London to Montreal, logging in 243 hours at sea. During long stretches of open ocean, we scout for marine life, and I also use the time to watercolor.

Isbjørnhamna, or Bear Island, should properly be named Bird Island for it is aswarm with millions of nesting birds. In staff-operated Zodiacs we circumvent the jagged cliff faces, a-riot with squawks, trills, and chatter. Sea stacks are silhouetted against a nacreous sky, some as majestic as Rodin’s Balzac, others as squat as a toadstool. Tim, a staff geologist, follows two other Zodiacs through a sea-eaten archway that opens up to a sheltered cove of massive, white-spattered rock walls, the grandest Jackson Pollock mural ever created by bird guano.

“Whales!” and everyone at dinner, jumps up and heads for the Bridge or the bow where dolphins bow ride. We count forty-some humpbacks that cavort on both sides of the ship flashing their magnificent, white-topped flukes. Guests share binoculars, and scopes, and as I look around me, I see unabashed expressions of sheer wonder. It’s a fiesta of cetaceans; humpback, fin, minke, dolphins, and in the distance, a possible sighting of a lone blue.

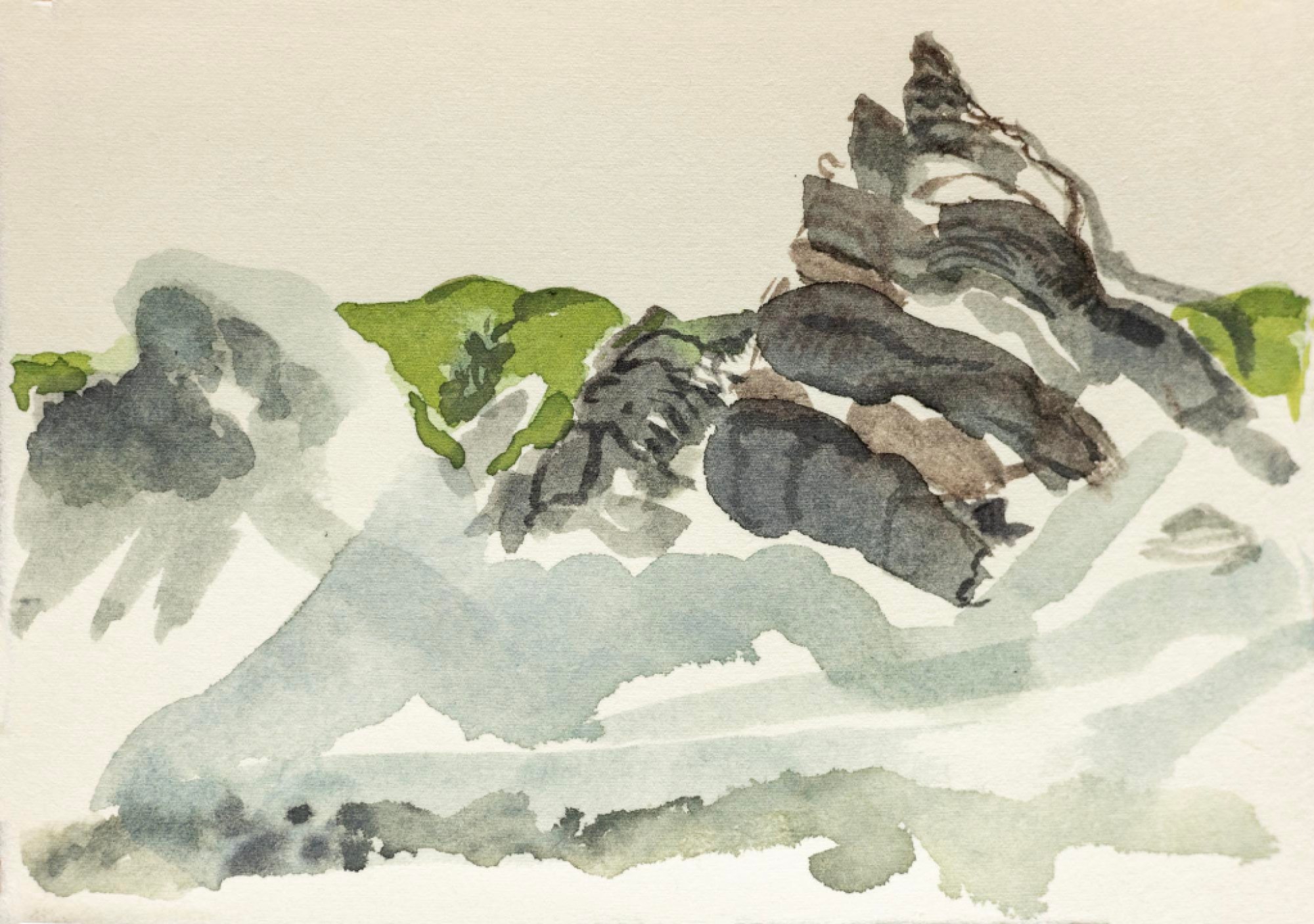

Then, we sail to Jan Mayen, the northernmost active volcanic island on earth, a hot spot along the mid-Atlantic ridge, that serves as a military base for Norway and in 2010 was designated a Natural Preserve. Some of us walk along the military road to a viewpoint, careful not to tread on the delicate fauna it bisects. The volcano was last active in 1985, and now emerald mosses, lichen, and dandelions creep up the slopes of the Seuss-like black lava formations. Little mounds of chlorophyll green moss, as bright as a shrill piccolo, signal Spring in the Arctic.

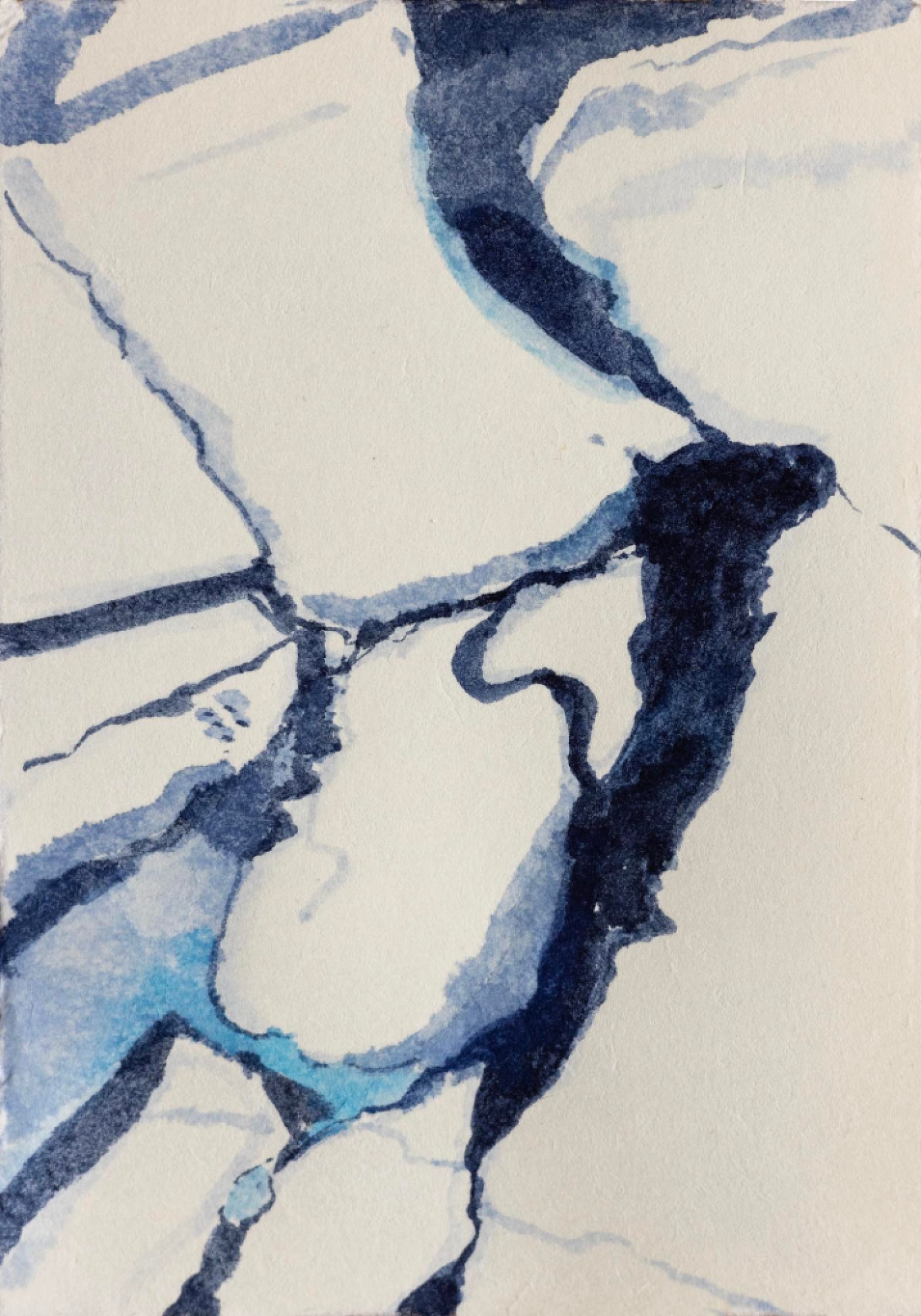

At 3:30 a.m., I peek out of our stateroom window, a momentary tinge of pink blushes the sky, the closest I get to seeing a sun rise. No gloaming, no long shadows, no clock-driven time. I drift toward sleep but am aroused an hour later by crash, crunch, smash, as we break through a wide field of ice. This is no time for sleeping — we hurry to the bridge to see the ship’s path carved through massive amounts of sea ice. More patterns! Deep indigo sea frames continents of ice in motion. Synaptic, arterial, muscular, bold.

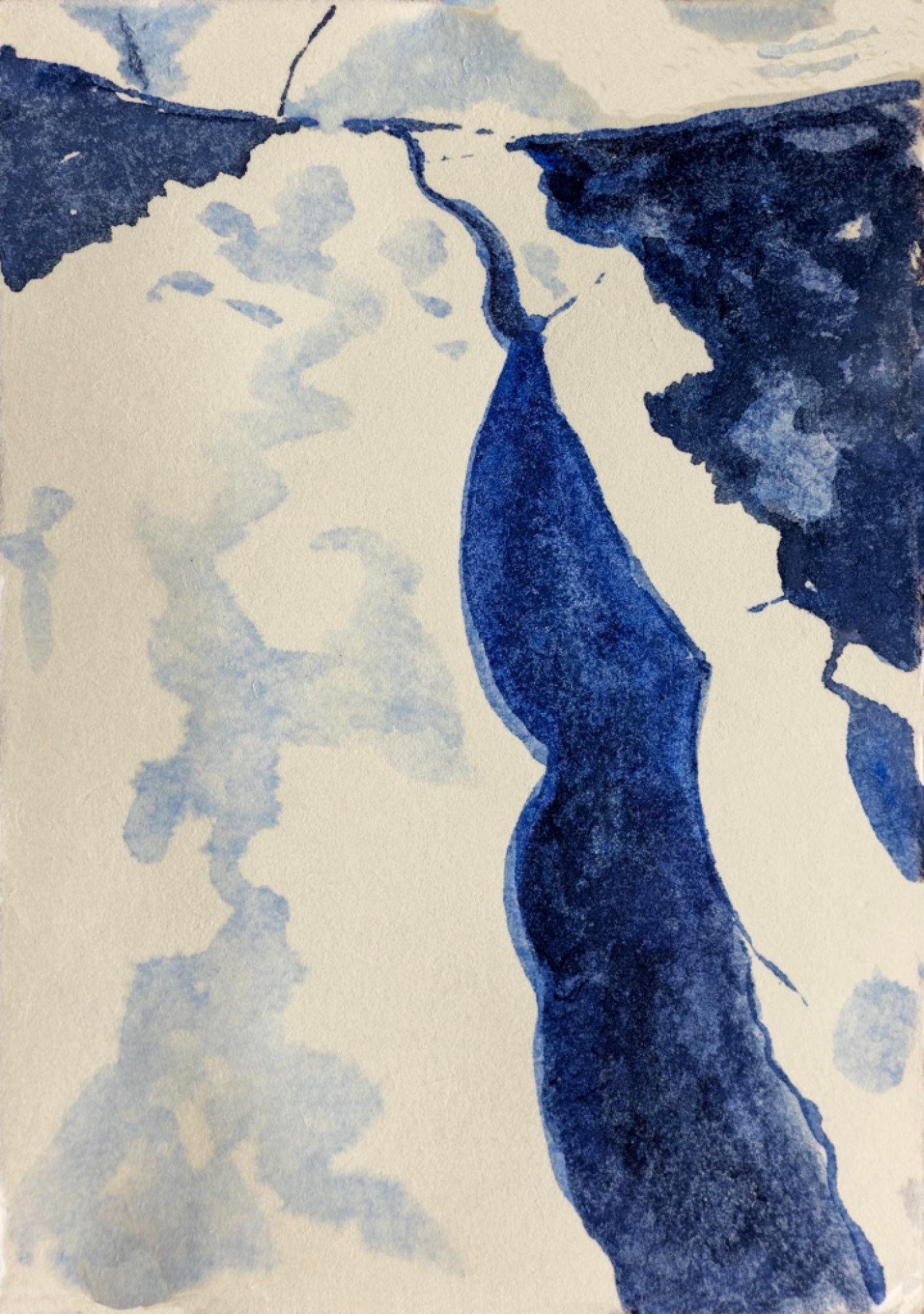

Data collected by NASA scientists charting sea ice for over fifty years shows that the Arctic ice is shrinking 12.6 percent per year. We navigate through thousands of slabs of ice: one year ice, multi-year ice that is 12-15 feet thick, pack ice, drift ice, pancake ice. Currently the multi-year ice makes up only 1 percent of total pack ice coverage — a recorded loss of 95 percent since 1985. However, Gretel writes to me that her Greenlander friends are in luck, calling this “a good year for ice,” and thus for hunting. For our ship it’s a jigsaw puzzle challenge, but also a chance for us to see wildlife: possibly a polar bear, pelagic birds, bearded seal, and walrus, as we carefully avoid glacial icebergs, hard as steel, like the one that sank the Titanic. Layers of ice are earth’s memory. Yearly seasonal ice accumulates into multiyear ice, like stored diaries, and glacial ice is no less than planetary history. Scientists continue to record losses from the archive of ice.

I imagine that for Captain Martin Graser and ice navigator Finn Mackeprang it is frustrating, slow work to maneuver through all of this. To go faster would be dangerous so they pick and choose our route, and the endless fog doesn’t help. But the Captain tells us, “It’s a challenge, like a strategy game, to do my best to dodge storms, navigate ice, in all kinds of weather — that is what makes my job so interesting.” They rely on ice radar to help fill in the bits one cannot see. Due to the southward flowing current the ice is in constant movement, so even one-day old ice charts are inaccurate. The extra maneuverability of the ship’s Azipod thrusters means it can deftly get through an ice-clogged area. After three hard days and nights forging ahead, often through ice-clogged waters, in a swallowing fog, we arrive in East Greenland and head to the shelter of Kangerdlugssuaq Fjord. In the morning we explore the fjord. Tim sidles the Zodiac close to describe the metamorphic rock formations, and Macduff asks, “Can we get in close enough to just touch the rock? I want to touch Greenland.”

[Click to enlarge]

Lars (Unqaaq) Abelson, an Inuit from Sisimiut, the second largest city in Greenland on the coast of Davis Strait, is an onboard cultural specialist. He comments that along the west coast of Greenland, near his town, the rapidly retreating Jakobshavn Glacier has shed tons of ice. The Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier, the largest tidewater glacier on the more remote east coast of the Greenland ice sheet is also retreating dramatically. The glacier’s floating part, its “ice tongue” melted and broke off. We Zodiac among the remains; giant glassy icebergs — and what we see are only the tips, 90 percent lies beneath the surface. Among these shifting frozen sculptures, circles of ice float like a field of white and turquoise lotuses. For a moment, it’s completely quiet, and I can hear the eider ducks calling to one another, a haunting loon-like cry. Slashes of sunlight spotlight the peaks of glaciers on a mostly cloud-covered day. Landmarks disappear behind fog, and only the memory remains. The fog lifts, like a rebirth. I wonder if death is like walking into the fog, merging with emptiness, leaving behind only memory, that, in turn, fades with time.

A slight breeze wrinkles the water’s surface, and if this skin could peel back like a grapefruit, what wonders could I see, blackness teaming with life, from single-celled frolickers to massive cetaceans. I’m afloat on its surface, seven stories above the water and know that beneath me is a universe of living, swimming, consuming, expelling, procreating creatures from the primordial to the highly sophisticated.

It’s so achingly beautiful, more so knowing that it is leaving us, the end of an era, the end of ice, and the climate, as we know it. Hard to know how to comprehend the All of it. Indigenous, subsistence-hunter lifestyles, and those peoples with the least impact on the phenomenon of climate change will suffer first. With climate change entire ways of surviving in the polar north will disappear, or radically adapt. Besides the walrus lacking purchase on ice floes, the polar bear lacking ability to hunt, and nurture young, are the Inuit who are expert naturalists and have for centuries survived in these extreme, tough environments. They will live with the loss of the protective ice caps that cool our fevered mother Earth and support this fragile life on the margins. But its impact affects all of us, in cities, farms, coastal regions, and inland. We are one body and our weather, our internal weather, our sense of what is normal is drastically changing. Certainly, there will be opportunists angling to make a profit over the last bits of resources and the newly uncovered real estate replete with minerals to exploit. But we carry weather within us, and we are all in this together. How will the shifts in climate affect our mood, our willingness and resourcefulness to survive? But overlooking the bow, past midnight in this time of endless sun it’s hard to dwell on what comes next. Three colors and an immensity. The force of sila, weather, and our impact on this delicate system, foretell what hangs in the balance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.