The Ever-Changing Evolution of Landscapes

Capturing the Moment of Last Shadow and

First Light with Artist Robin Gowen

By Roger Durling | Photos by Ingrid Bostrom

June 1, 2023

“You need to feel you’re in danger in order to do good work,” states Robin Gowen, early in our conversation. “Painters deal in jeopardy. We must make things that are not safe, that will be a surprise and a discovery — to the artist as much as the observer. Without that desire to take risks, painting can become pretty and predictable.”

It is the presence of urgency and conflict in all of Gowen’s work that has made me an ardent admirer. She is a Santa Barbara artist who deserves overdue prominence. Gowen is Sullivan Goss’s longest-represented artist and is currently exhibiting her 12th solo show at the gallery. Titled Last Shadow & First Light, this expansive exhibition — more than 30 paintings on display until July 24 — coincides with the announcement of a new monograph surveying the career of the artist.

The show can be evenly divided into two groups of landscapes, and there’s an inciting dialectic amongst them. Some works depict a California during the drought, while others showcase topographies after the recently welcomed yet unexpected downpours. In the paintings representing the drier geography, Gowen manages to convey an insistent tussle coming from all the compromises that have to be made in order for the vegetation to survive.

“A painting speaks of motion and should show a sense of the act and fury that created it,” Gowen says. “In the end, painting is a performance art. On the canvas is the gesture — a tree racked between heaven and earth, a stone about to tumble, a cloud morphing into haze.”

The movement of her brushstrokes — frantic and forceful — conveys a strong will for subsistence. “When I was doing the drier paintings,” she reveals, “they felt like a prayer for rain.” The toil continues but in a different way in the “wet” terrains. She explains, “The wet paintings are rejoicing — and yet combative. It’s very active. It has a great deal of movement. The living thing is responding to its environment.”

This idea is most evident in the centerpiece of the exhibit, a large canvas named “Winter Walk on Vieja Drive,” illustrating old oak trees with younger eucalyptus lurking in the background. The twisting branches are expressive, ominous, and resilient. “It is a frenzy of branches and trees, but each of them has a logic that I find fascinating,” says the artist about her composition. “People believe trees are pleasant and soothing,” she continues. “I don’t see that at all. I see the desire for life, and making a compromise between light and gravity, which is trying to take it down. You see it being pulled between those two opposing forces. You also have the native plants and the alien ones managing to coexist. You end up with this gorgeous struggle.”

“Winter Walk on Vieja Drive,” 2023, is the centerpiece of Gowen’s show currently on view at Sullivan Goss Gallery | Credit: Courtesy

“One of Robin’s greatest skills is the way she sees color; in a baking hot summer sky, her eyes pick up the lime green that sizzles on top of the blue,” says Susan Bush, curator of contemporary art at Sullivan Goss. “She can see neon pink undertones pushing through a field of high-meadow grasses and the chocolatey blue depths that make up canyon shadows.”

When I bring up this command of color to Gowen, she gleefully explains, “There’s a phenomenon that I call ‘the darkness in the eye.’ When you stand out in the field, painting, your pupils close down, to make the brightness tolerable and protect the eyes. But when that happens, the range of value you are capable of perceiving closes down, too — you see the whitest whites grayed and so too, the darkest darks rise in value to be a dark gray, no longer black.”

Our reaction to the brightness mutes the range of value and color. This leads to a very common issue in plein air painting where the painter unconsciously depicts a less brilliant world, because he or she is no longer seeing it as it really is. “So the only cure I know for this is to always remember the problem and intentionally paint more intensely as I work in bright light,” Gowen explains. Moreover, she excitedly goes on to describe the simultaneous contrast of color in her work. “If you place an apricot next to a turquoise, the two colors will highlight each other’s role in the image,” she says. “But if you place a blue-green next to a green, they will have a dulling effect on each other, lessening the impact on the viewer. To excite the eye of the viewer, opposite colors even in quite small quantities can really cause vibrations.”

I wanted to know more about the artist behind these pulsating and stirring paintings for a long time. I met with Gowen at her home over three sessions of more than 90 minutes each in late April/early May, as she was finishing the pieces for the current show. Our conversations were dense and intellectually stimulating. She’s a great raconteur with deep knowledge and observations about art and life.

Before my first visit, fellow painter and friend Hank Pitcher described her to me: “Robin is remarkably knowledgeable about a remarkable range of topics. She has a childlike curiosity about everything, and a scholar’s love of research and accuracy.”

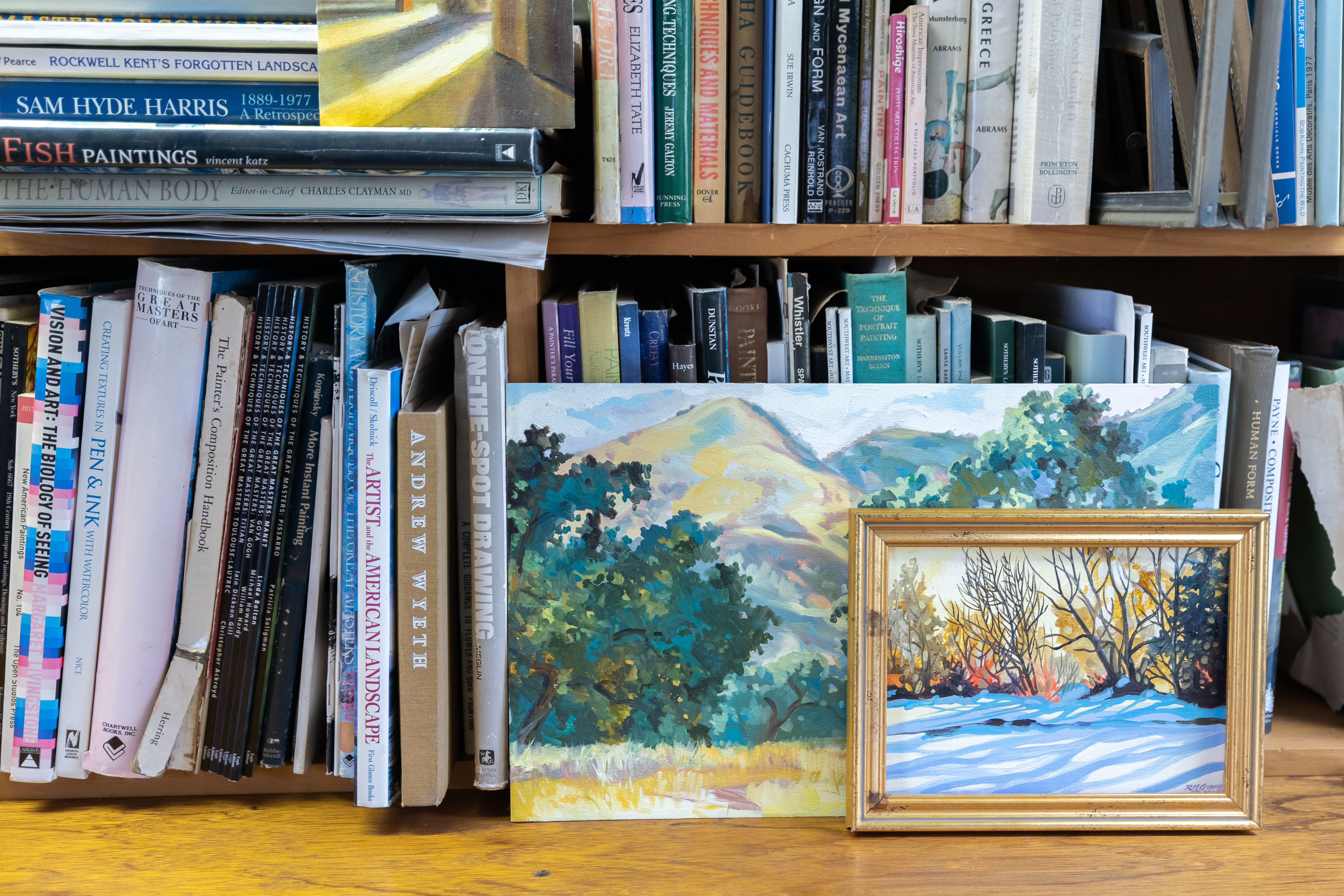

We met in her studio, which is a lovely greenhouse located at the end of her driveway; plenty of light and drying canvases enveloped us, as well as the comforting smells of oils and turpentine. Kiwa, the next-door cat, made himself at home and seldom beckoned our attention.

“I paint fast and hard. I like immediacy in the painting process, not layering or overpainting,” Gowen divulges. “I treat the oils as if they were watercolors.” She works until late hours of the evening, fueled by the need to finish what she started and to be as true to her initial vision as possible. “I paint because I cannot stop. It’s not a choice. I have to respond. I like the power that the painting gives me. There’s a rush to it. This is about the power of possession,” she says. “Afterwards, I don’t know who painted what I see on the finished canvas.”

But she’s quick to point out that this act of possession works both ways. “Sometimes I feel I’m a vessel. The landscape wants to have a vessel. I’m capturing it in time. All paintings are time portals. I’m preserving, catching a moment.”

I inquire about the mostly horizontal composition in her paintings, which remind me of the movie frame. “It means you get into the painting and get lost for a while,” she replies. “You can travel in it for a while. I have done some vertical paintings, but it is not what I prefer.” She also works quite often in large dimensions. “I like painting big things,” she discloses. “I like to do big paintings because it allows a degree of immersion. There’s a challenge to it. If you’re going to take a pratfall — it’s going to be a big pratfall.”

“I paint because I cannot stop. It’s not a choice. I have to respond.”

Gowen was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1957. Her parents met when they were in graduate school in Minnesota. Fred Gowen, originally of Stratham, New Hampshire, was studying plant genetics. His daughter remembers him as a Don Quixote type, idealistic. He eventually got a job at the University of Nebraska. Her mom, Florence Wen Gowen, was from a wealthy family in Beijing, China, and got a master’s degree in library services. She gave up her career to raise her three children. She taught Robin painting when she was 3 years of age. “I learned how to paint before I learned how to read,” she states.

Her mom gave her the book The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting when she was 9 years old and explained to her that Chinese artists in the Wen family learned skills from copying the great artists. Florence put her daughter on a meticulous course of replicating the black-and-white illustrations from that book. “That’s when I realized that she took my painting seriously,” says Gowen. With the book and her mom’s guidance, Gowen learned different types of brushstrokes. “What she taught me was the symbolism of all painting, the principle of translating the three-dimensional ever-complex particularity of the world into a two-dimensional expression,” she imparts.

In 1960, the family relocated to Western Nigeria under the auspices of USAID (United States Agency for International Development) so her dad could teach at the University of Ife (later renamed Obafemi Awolowo University). Young Gowen remembers being riveted by lizards and getting good at spotting snakes. “I was also fascinated by the complicated lives of moths, butterflies, and caterpillars.”

Dad had a gap between contracts and brought the family to his family homestead in New Hampshire. It is there that Gowen had her first appointment with an ophthalmologist and her parents were told that she was legally blind. “I got glasses,” she reminisces, “and realized that there were individual leaves on a tree. I haven’t gotten over that. I loved being able to see. I loved being able to see all this drama. There’s so much detail in the world, and before I had glasses all of that was nonexistent.”

The family moved back to Nigeria for Frederick’s research job in 1966, and he eventually moved the family to upstate New York in 1970.

In 1973, Gowen was accepted to the highly selective private school Phillips Exeter Academy, where she received further instruction in painting. She took a class where they drew and painted a nude model — which had a profound impact. “No matter how good you are at painting, the nude is important,” she says. “There’s a visceral importance to it. When you stand in front of the nude, you have to face that that’s who you are: imperfect, flesh and bones. And yet with all of that, there’s so much more than physicality. You become aware that you are prone to damage, that you’re in jeopardy.”

During high school, she was failing math but painting a lot. “Exeter taught me that when you are curious about something, go out and find out about it,” she imparts. “Research is key for responsible living.” The school bought two paintings from her and placed them in the infirmary.

After Exeter, she was planning to go back to Nigeria, but she didn’t get a visa, so instead she attended Wellesley College. She majored in English and East Asian Religion, Neo-Confucianism. “I wasn’t fond of Buddhism,” she reveals. “I like the philosophy of personal responsibility. The one thing I got from Wellesley was a coterie of good friends.”

After college, she couldn’t get a job, so she went back to Africa, where she taught English composition in a secondary school. “Africa can be addictive,” she confesses. “I put a limit on it. One year, and then I came back to the U.S.”

She moved to New Haven, Connecticut, and got a job in the art department of American Scientist magazine. In New Haven, she met her future husband, Bruce Tiffney, who was a professor of evolutionary biology at Yale. They met at a party, and he was rude to her, telling her, “The female of the species is always so short.” Regardless, she invited him to lunch, and it ended up being three hours of talking. A year later, they were married.

Tiffney was strongly supportive of her work. He set up his father’s old drafting table in his apartment and told her, “Now you have a place to work.” After he got a job at UCSB in 1986 (where he is now Professor Emeritus), he encouraged Gowen to concentrate solely on her art.

“He gave me the license to do this,” she states. “When he was collecting fossils, I would tag along all over California, and I was drawing and painting.”

In 1992, they welcomed their child, Theo.

One day in 1996, Gowen had just gotten her work into a gallery in Carmel and decided to have a celebratory lunch at Arts & Letters Café. She struck up a conversation with Frank Goss — who owned both the café and art gallery at that time — which led to her being represented at Sullivan Goss Gallery. She has had a show at the gallery roughly every two years since. “I like the people,” she shares. “They’re very constructive.”

One of the many remarkable things about Gowen as an artist is how she just keeps evolving. “I don’t like being one Robin Gowen with one particular style,” she explains. “I have five or six different horses all attached to my wagon. My goal is to keep getting better. I try to paint so that my paintings will last long past my lifetime. Once living things and their places become represented in paintings, they might possibly live forever. I’ve made comments before about the time travel that art allows, how artists can snatch from time and its changes, glimpses of a time that passes even as we paint.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.