Santa Barbara’s Century Man

Roke Fukumura: Baseball Star, Internment Camp Survivor, Hardworking Hometown Hero

By Tyler Hayden | December 22, 2022

Roke Fukumura is an early bird. Always has been. Five days a week for the past 32 years, he’s arrived at Tri-County Produce before dawn, more recently in an Easy Lift van because of his waning night vision. “I come early or not at all” was his response after his boss suggested he start a little later.

Standing outside the lower Milpas Street grocery store, Roke can hear the train and smell the ocean. Across the street is Cabrillo Park, where, at just 14 years old, he played semi-professional baseball. Up the road on the Mesa is where he was born on his family’s farm. Roke rarely strays far from Santa Barbara, and when he does, he doesn’t particularly enjoy it. “This is home,” he said.

Roke’s first task of the morning is to help unload the trucks. He lifts 50-pound sacks of onions like a much younger man, though he can no longer hoist them onto his shoulders. The aches and pains are too much. When his coworkers encourage him to try something lighter, like mushrooms, he shakes his head. His Japanese-American father, who raised five children almost all on his own through the Great Depression, World War II, and an internment camp, had a saying: “Bear it.”

Roke spends the rest of the day trimming and stacking the fruits and vegetables that fill Tri-County’s racks. He’s also quality control. As he has throughout his career, including as the store’s main buyer, he takes immense pride in his work. He beams when customers compliment the produce, which is among the crispest and tastiest anywhere on the South Coast. “I enjoy serving the public, and I meet very wonderful people,” he said. “I love it.”

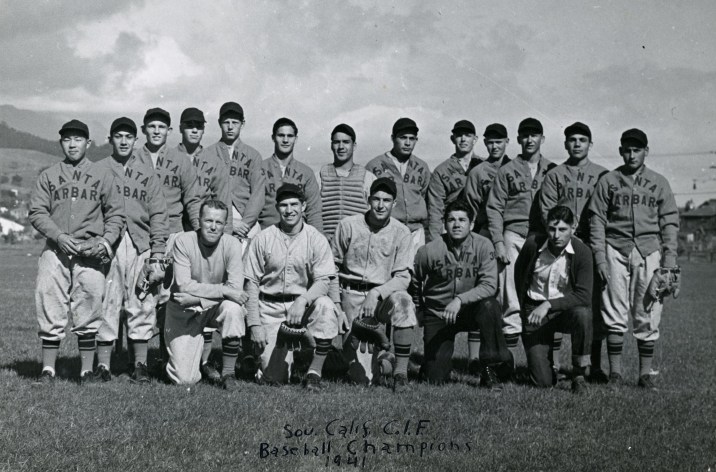

Once he clocks out, Roke occupies himself with the other thing he loves: sports. “Anything competitive,” he explained. He’s a Dodgers fan but especially appreciates Clayton Kershaw’s intensity on the mound. That same fire to win still burns in Roke’s belly, more than eight decades after he helped Santa Barbara High School secure its first— and still only— CIF Southern California Baseball Championship.

On November 26, Roke turned 100 years old. To him, it was just another trip around the sun. No big deal. But his longtime friend and employer, John Dixon, convinced the star shortstop to let others celebrate him and his rich life. On hand that day among the balloons and cupcakes were friends and family and a whole contingent of dignitaries, including a couple of mayors and a member of Congress. Jokes were told and proclamations read. They said Roke embodied the American dream, and they apologized on behalf of the U.S. government for violating his rights during the war.

Roke was appreciative but brief on the mic. Only later did he begin to tear up. “I thank John for bringing these people here,” he said. But the vulnerability didn’t last long. Soon he was back to his smiling, straight-talking self. People wanted to know his secret for long life. Less meat and more vegetables, he replied. Keep your body moving. Forget about politics. And above all, he said, “Stay single.”

Riyokui Fukumura, whom everyone has called Roke (row-kee) since grammar school, is the baby of the family. His parents migrated to Santa Barbara in 1904 from a village in Japan’s Kumamoto prefecture, living first in Mission Canyon before leasing a six-acre piece of farmland on the Mesa. Japanese residents weren’t allowed to own property at the time. The Fukumuras grew “a little of this and a little of that,” Roke explained, including carrots, spinach, and sweet peas. “The town was so small back then, you could only grow so much and sell so much.”

The family home was a semi-abandoned two-story house at 1919 Cliff Drive (the current site of the Mesa Verde restaurant), and it was there that Roke’s mother gave birth to him with the assistance of a midwife. They didn’t have a lot of toys, but the children had plenty of space in which to play, as the neighborhood back then was almost all agriculture. There was a strawberry farm around the corner, and “Porky Joe” next door had a team of horses that plowed the fields. You could see the Mesa lighthouse from the home’s upstairs windows, Roke recalled, though the 5,000-candle-power bulb would cast spooky shadows on the walls.

When Roke was 5 years old, his mother, Gima, died of pneumonia. He says so matter-of-factly, but his brow furrows at the memory. That left his father, Kameki, on his own to look after the children. “He worked hard and supported all of us,” Roke said. “I give him so much credit for that.” Every morning at 6 a.m., Kameki loaded his Model T with the harvest and sold what he could in town, making sure to be back by 7 a.m., in time to take the kids to school. He would farm all day until he picked them up at 3 p.m. then head back into the field until dark.

While Roke fed the chickens; his brother, Tom, tended to the horses; and their sisters washed the dishes, Kameki took care of everything else. He bought and disassembled two worn-out sewing machines and rebuilt one with the working parts to make their nightgowns and other clothing. Kameki’s most oft-repeated lesson was to never steal. Ever. Under any circumstances. “We were poor but we were taught not to get sticky fingers,” Roke said.

Even though the house had three big bedrooms upstairs, the protective patriarch and his children all slept in the downstairs master so he could keep an eye on one daughter who had recurring whooping cough and another who would get very bad earaches. They used kerosene lamps and a wood-burning stove and listened to records on a hand-cranked phonograph. “My father was a tough guy, but he was also very gentle with us in a lot of ways,” Roke said.

All of the Fukumura children took turns helping their dad with the farming. All of them except Roke. For whatever reason — maybe because he was the youngest, maybe because he showed budding talent from such a young age — Kameki cut Roke loose to play sports after school and on the weekends. He attended McKinley Elementary School, La Cumbre Junior High, and Santa Barbara High, and played baseball and basketball and ran track. “I was short,” he said, standing a little over 5’2″, “but I was fast.”

Roke set a high school record in the 50-yard dash and even qualified to run in the CIF Championships at the Los Angeles Coliseum. But the day of the track meet, he faced a dilemma — travel to L.A. for a shot at personal glory or accompany the baseball team to their quarterfinal game scheduled for the same time in Oxnard. “I went with the team,” Roke said. “They needed me.”

That 1941 squad was stacked. It featured a handful of football stars who were just as talented on the diamond, including pitcher Dan Zuzalek, who led the team with a .384 batting average. Second baseman Johnny Latham hit .375 and batted second in the order behind their leadoff ace, Roke, who was the only Asian-American starter. Being a little shy, Roke said, he didn’t muster the courage to try out until his sophomore year, at which point his classmates practically begged him to lend his speed and arm to the Dons.

They were good, but they weren’t flashy, said Roke. “We stuck to the basics — bunt, steal, hit, and run. You know, small ball,” not unlike the strategy of today’s Santa Barbara Foresters that makes them so hard to beat. Roke was especially deadly on the basepath. He stole 20 bases his senior season, owing to his previous experience with Santa Barbara’s semi-pro team at the time, the Hi Stars, who played Sundays at Cabrillo Park against regional rivals like the Carpinteria Merchants.

“I could read the pitchers,” Roke said. Once he was on base, he explained, he would often reach third on a bunt from Latham. “That was one of our plays.” Roke was also the team’s hype man, stoking spirits and encouraging effort when the chips were down. Sometimes he’d get a little too worked up, he admitted, and the coaches would tell him to take it easy.

The Dons won their quarterfinal game in Oxnard, then beat Pasadena in the semis, teeing them up for a showdown with Long Beach for the championship. Long Beach had their own weapons, including their starting pitcher, a 6’2″ hurler who went on to play for the Cleveland Indians. He stood more than a head taller than Roke, which was pointed out to him when the teams ran into each other outside their locker rooms. “Look! They brought their water boy!” the opposing players snickered. “I stole four bases that game,” Roke remembered with a wry smile.

The contest was one for the ages, a pitching duel that went 17 innings and remains the longest CIF baseball final in section history. The Dons were the away team, so the crowd was against them, but they endured and took home the trophy, thanks in no small part to Roke’s near-perfect defense. “Roke’s fielding at shortstop was outstanding,” Coach Skip Winans told reporters at the time. “It was a grand time for us,” said Roke.

But the good times didn’t last. Less than seven months later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and Roke and his family were unceremoniously packed and shipped to an internment camp in Poston, Arizona, along with nearly 18,000 others. The Japanese American Citizens League, to which the Fukumuras belonged, advised them not to resist. It would only make things worse.

For the next three years, the family lived in a single 20-by-25-foot room. Roke, who was 19, tried to enlist in the Army as it was one of the few ways to escape imprisonment, but he didn’t pass the physical exam. Ironically, the Santa Barbara speedster was rejected due to a congenital bone growth in his leg.

Roke was instead assigned as a cook, responsible for feeding 300 people in his barracks with whatever rations the government gave them. Sometimes they received beef hearts and liver, which, having grown up mainly on vegetables and the occasional chicken, he had no idea what to do with. “Luckily, we had a cook from a hotel who knew how to bread and prepare them,” he said.

Every day after work, Roke and his brother played baseball with the Block No. 308 team on a makeshift field they called Yankee Stadium. They were a particularly effective double-play duo with Roke at shortstop and Tom at second. “That gave us something to do,” Roke said. “It kept us going.” At night, their father would sing them traditional Japanese songs.

Not one to complain, Roke doesn’t say much about his time at the camp, other than that it happened and it’s done. He appreciated the apology during his birthday party, he said, but he’d already heard the same thing from Ronald Reagan. What good does it do to dwell on the past? A passage from the National Archives, however, paints a vivid picture of what life was really like in Poston:

The relentless summer sun scorched the earth, and the frequent winds whipped the sands into blinding dust storms. In the winter, chilling gales easily penetrated the walls of the flimsily built tarpaper barracks and through the wide cracks in the flooring. The infrequent but torrential rains quickly turned the parched walkways and roads into a slippery, treacherous, and muddy quagmire. The extreme environmental conditions added to the hardships of internment.

When the war ended in 1945, the family moved back to the house they’d been renting on Ontare Road. Some of the neighbors objected, but their landlord told the complainers where to shove it. It was hardly the only time the Fukumuras experienced discrimination in the wake of the war. In one instance, when Tom and some friends were driving cross-country, they were chased from an Oklahoma gas station by an attendant with a gun.

Having been denied the opportunity to attend college, Roke followed in his father’s footsteps and tried his hand at farming, first at a property on El Sueno Road, where he rode a mule named Freddy and a horse named Pony, then in Fresno for a few years, where he grew watermelon. By 1950, he was back in town and had traded his mounts for a truck when he was hired by Harry Bowman at the banana house and wholesale produce market that eventually became Tri-County Produce.

Roke worked as Bowman’s buyer and was frequently on the road. He enjoyed his boss’s full confidence and, armed with a stack of blank checks, visited suppliers all over the region. He purchased carrots, cabbage, lettuce, celery, cucumber, tomatoes, and pumpkins from Lompoc; lettuce, squash, and beans from Santa Maria; cauliflower, broccoli, and strawberries from Guadalupe; and celery, romaine, and more cauliflower from Arroyo Grande. “I would take off at 5:30 in the morning and be back by 7:30 at night,” Roke said. “I put in a lot of hours.”

Roke was also starting a family. He was married in 1954 at the First Congregational Church and honeymooned for a week in Las Vegas. His son, Ron, was born two years later and his daughter, Sharon, the year after that. The marriage, however, was a painfully short one. With the children still very small, Roke’s wife realized family life was not for her and left them. Like his own father, Roke assumed the mantle of single dad and remained utterly devoted to his young ones. They went to Disneyland and always had a dog. He never remarried.

Roke climbed his way up to store manager, and in 1972, he was lured away by Santa Cruz Markets, who promised him less time on the road and more time with his kids. A few years later, he was picked up by Jordano’s Inc., where he remained until his “retirement” in 1991. It was then that Tri-County’s new owner, Jim Dixon, convinced Roke to come back and work for him.

The two were very close. Jim also came from modest means, and his father was also a farmer. “He treated me so nicely,” said Roke. “He was just super.” Three days a week, they would eat lunch at Carl’s Jr. up the block. They each got a burger, split a salad, and drank water, all for four dollars.

Jim’s son, John, met Roke when he was 8 years old — at that point, Roke had already spent 50 years of his life in the Tri-County building — and they quickly formed their own bond. The three became known as Los Tres Amigos, frequently spending holidays and other family gatherings together. Jim passed away six years ago, but John and Roke have soldiered on. John has recently made it a habit to hug his longtime pal every time he sees him.

As spry as he appears, Roke is thinking about hanging up his apron, this time for good. “When you get to be my age, you don’t have any fat anymore,” he said, rubbing his hip. “You’re all skin and bone.” He also suffered a great personal tragedy not long ago that sapped some of his remaining strength. His son, Ron, with whom he shared his Berkeley Road home, died in June. He doesn’t like to talk about it.

Roke always doted on his children. He helped Ron finance an auto body shop, and when his daughter, Sharon, who lives in Camarillo, was starting her own family while trying to get a flower business off the ground, he drove south every week to babysit. He also helped care for his three older sisters during the last years of their lives. They each reached their mid-nineties. Now, Roke heaps his affection on his three grandkids, who love him right back.

If and when he actually retires, Roke will have more time to follow sports. And to offer his critiques. The Los Angeles Angels, for instance, need to rebuild their team in a bad way. While they have two powerhouses in Mike Trout and Shohei Ohtani, he said, the remaining roster are little more than journeymen. And don’t get him started on the Los Angeles Rams. “I used to be a fan, but something is wrong with them,” he said. “Their defense is terrible. Last year they were slaughtering quarterbacks, but this year they aren’t doing anything.”

But what really gets Roke’s goat is watching batters swing for the fences and hit nothing but air. “You don’t see .300 hitters anymore,” he said. “More like .240.” Like Cody Bellinger. “He swings so hard he misses. His head is all over the place. I think to myself, ‘Why don’t they watch the ball?’”

Maybe with more free time, he’ll travel a bit. See the world. Nah, he said. He once flew to Japan to visit his parents’ village but found the country too fast, too busy. On a trip to Hawai‘i, he grew bored. Santa Barbara is just right, he said. “I like it here.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.