Caught in the Rental Crunch

Our Readers Speak Out on the

Struggles of Renting in Santa Barbara

By: Ryan P. Cruz | December 15, 2022

It’s no secret that Santa Barbara is expensive. This year, U.S. News & World Report ranked Santa Barbara the fifth most expensive city to live in in the U.S. And according to LivingCost.org, a crowdsourced database that calculates and ranks the total cost of living for more than 9,000 cities across the world, Santa Barbara is in the top 0.1 percent — the most expensive in California, second in the U.S., and fourth in the world — with an average cost of living of $3,455 per month.

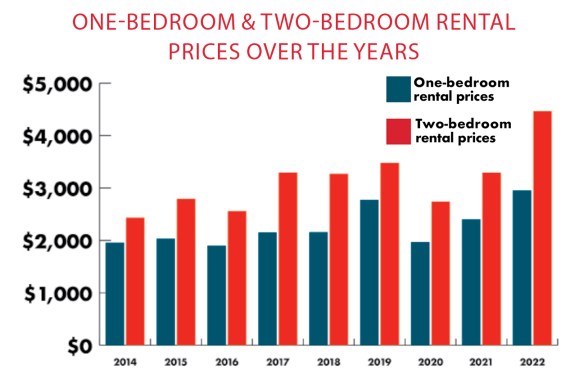

Back in December 2014, someone looking for a one-bedroom rental could expect to find a listing for around $1,900 a month, according to data collected by Zumper, which analyzes active rental inventory in real-time and has kept track of prices over the past eight years. A two-bedroom in Santa Barbara in 2014 would run close to $2,700.

But since then — and most dramatically in the past year — these rates have skyrocketed, exacerbated by a higher demand for rentals, a lack of new affordable units, and an influx of high-salaried remote workers who have moved into town to enjoy a piece of what is considered one of the best places to live in the world. Based on limited listings collected by Zumper, the average rent in Santa Barbara as of December 3, 2022, was $2,815 for a one-bedroom apartment and $4,200 for a two-bedroom.

To get a fuller picture of the prices renters were seeing currently, the Independent conducted its own review into one- and two-bedroom units listed on Craigslist from Goleta to Montecito in the early weeks of December, compared to those listed throughout the month of September 2022.

In September, the average one-bedroom rented for $2,655, and two-bedroom apartments averaged $3,843. Three months later, a review of more than 300 active listings in December showed the prices had jumped even higher. Out of more than 120 one-bedroom apartments listed, the average price was $2,935, with listings ranging from $1,248 to $5,000. For two-bedroom rentals, the average of the more than 100 units listed was $4,464, with the cheapest listed at $2,400 and the most expensive — a two-bed, three-bath home overlooking a golf course in Hope Ranch — offered at $10,750 a month.

“I can’t talk to anybody who works here or lives here without talking about housing,” said Senator Monique Limón, who met earlier this month with members of the League of Women Voters of Santa Barbara’s Housing Committee and Santa Barbara County Action Network (SBCAN) for a roundtable discussion on the local housing crisis.

The topic was also at the center of discussion during a recent Santa Barbara City Council meeting, in which the city decided how to divide the $14.6 million budget surplus. After pleas from housing advocates and city workers, and a lot of back and forth, the council decided to keep half of the surplus in the city’s rainy-day reserve fund, give a quarter toward employee salaries and pensions, and the remaining quarter to the newly created Affordable Housing Trust Fund. Specifically, the housing trust gets $3.6 million, minus $250,000 toward a program that would provide legal counsel to tenants facing evictions.

In October, the Santa Barbara Tenants Union organized a “Rent’s Too High Rally” at the courthouse, where dozens of locals shared their rental horror stories, and advocates pushed for a rental registry and rent control to protect tenants, which make up 60 percent of the households in the city.

The Independent recently asked its readers to provide their own tales of tenant troubles, and our inboxes were flooded with locals eager to share their stories. What we received were entries covering the wide spectrum of Santa Barbara residents: a family of middle-class business owners cramped into a tiny apartment, a single mother struggling to give her son the same Santa Barbara childhood she enjoyed, and Santa Barbara natives who spent their lives on the South Coast, now scattered across the country in new communities, still hoping for a day they can return and raise their children in their hometowns.

“This story might be a few years late,” wrote Eric Holguin, who was born and raised in Santa Barbara but has been living in southern Nevada since the spring of 2015.

Before he moved, Holguin said he was doing something that he loved — coaching football at his alma mater Santa Barbara High School — but with two young children about to start kindergarten, he thought the timing was right to move to somewhere more affordable.

“I had a family to think about,” he said. “I miss it to this day.”

Holguin’s story was just one of many we received in the past three months. Some were unwilling to share their identities, fearing retaliation from landlords, or stuck in legal battles that are still unresolved.

One kindergarten teacher who wished to remain anonymous for this story was evicted from her apartment when a major local developer remodeled the unit and raised the rent. She has since moved to South Lake Tahoe, where she hopes to start teaching full-time next year.

“It’s really unfortunate that the city is losing another teacher when there is such a shortage due to high rent prices,” she said. “Santa Barbara will always hold a special spot in my heart, and it’s just soul-crushing that I was booted for a remodel.”

There were also uplifting stories: of people helping each other find housing, of mom-and-pop landlords offering consistent and quality rentals to long-term tenants, and of people being grateful to have even a small slice of Santa Barbara life.

What follows is a selection of some of the stories sent in by Santa Barbara residents — current and former — mixed with input from local experts, housing advocates, and city leaders on where we are, why we’re here, and what we can do about the rental crunch in Santa Barbara.

Full-Time Struggles of a Young Mother

Angelina Montalvo moved into her current apartment with her ex-boyfriend in 2019. When she first moved in, she said they “barely qualified,” and even with full-time jobs making $18 an hour, they needed to pay a double deposit to secure the apartment.

Since 2019, she says her rent has been raised three times, from $1,750 a month to $2,025. She now lives in the apartment alone with her son, whom she takes care of full-time on top of a job at which she works 60-80 hours a week while trying to focus on her studies.

“I’m not sure how much longer I can afford to live here,” she said. “Between rent, utilities, car payment, insurance, groceries, gas, and basic hygiene needs, I’m left with nearly $200-$300 to myself, which goes to my son’s sports,” she said. “I’m not sure how much longer I’ll be able to enjoy my hometown. As much as my son wants to stay here and live in Santa Barbara as I did, it’s most likely not going to be that way.”

Montalvo is one of an estimated 5,000 people on the waitlist with the Housing Authority of the City of Santa Barbara, which has built and manages about 1,450 units of affordable housing and provides support services to thousands of low-income households in the city.

“Two in five family households — or 30,000 households — in the city are considered lower-income, and most cannot afford the market rates of new construction,” said Jessica Wishan, CEO of Habitat for Humanity of Southern Santa Barbara County, during last week’s City Council meeting, where $3.6 million was earmarked toward fully affordable housing.

But even with programs like Habitat for Humanity and the city’s Housing Authority, which recently received the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art’s Gindroz Award for Excellence in Affordable Housing, the limited space for development and highly competitive market for any prospective properties have left housing advocates hungry for a permanent source of “flexible funding,” said Rob Fredericks, the Housing Authority’s executive director.

When a new property hits the market, the Housing Authority is forced to contend with private developers who have deep pockets and can close on an offer right away, where city agencies typically have a few layers of red tape to wade through before they can buy.

The $3.6 million recently put aside for the housing trust fund is a start, Fredericks said, but until there is a permanent source of local funding, there is simply not enough resources to provide for all those on the waiting list, leaving those like Montalvo — who is a low-income single mother but otherwise healthy — stuck behind a priority-first waiting list that moves seniors, veterans, and disabled people to the top of the list.

“About 75 percent of those eligible don’t receive assistance,” Fredericks said. “I’m hoping there will be additional funding for those on the waiting list.”

‘There’s No Home for Me Here’

Amber Rouleau is another Santa Barbara native, born and raised. Her grandfather Wilbur H. “Ping” Ferry was a renowned figure who, among other endeavors, supported tenants’ rights in the city.

Though her family sold her childhood Mountain Drive home in the ’90s and moved to the East Coast, she always wanted to return — “Hard to keep the S.B. girl out of town,” she says.

Six years ago, she and her husband sold their Connecticut home to have the chance to come back and live on the South Coast. For five years, the two rented a house on the Mesa, on a property with another tenant living below them.

“It worked well, and we were very happy,” Rouleau said. “We became friends with the neighbors and became actively involved in town. When the debris flow happened, we volunteered every single weekend nonstop for three months to dig out homes, parks, and trees. We are deeply connected within the community, enjoying the rare gift of lifelong friendships.”

Still, she saw her rent increase consistently each year, all the while, she says, the property fell into disrepair without any maintenance from the landlord.

‘I’m not sure how much longer I can afford to live here.’

“Zero work was ever done on the property — we had several inoperable windows due to rot, and we repaired anything we could ourselves to avoid her threats of additional rent increases,” she said.

Then last year, she says the landlord offered her an ultimatum: Their rent would be increased by 45 percent, their downstairs neighbor could be kicked out, and they could take the downstairs space at $9,000 per month as a short-term rental, or all the tenants could be displaced and the whole house would be listed on Airbnb.

Rouleau felt that neither of those options was enticing, nor did they sound legal, so she got in touch with the Santa Barbara Tenants Union for legal aid.

“We learned what our landlord was attempting to do wasn’t legal. We ended up hiring an attorney and landed on a settlement no one was happy with, and all parties had to move out anyway,” she said. Later, she found her former rental listed on Airbnb for $925 per night.

Stanley Tzankov, cofounder of the Santa Barbara Tenants Union, also spoke during the council meeting, advocating for more funding toward housing, where he emphasized the need for the quarter-million dollars toward tenants who often cannot afford legal representation.

“Many people don’t know that tenants don’t have a right to legal representation in cases where they’re served with bogus eviction notices, illegal renovations, and more,” he said. “So more often than not, they expect that they just won’t show up to court, and when they don’t, they’re out of luck, out of their homes, or forced into much higher rent or pushed out of town.”

Housing advocate and Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE) organizer Wendy Santamaria told the City Council, “Affordable housing advocates in the city have been discussing [right to counsel] as a way to really address the loopholes that a lot of landlords are unfortunately taking advantage of in the law. There are plenty of loopholes that truly cannot be mitigated unless there’s counsel, and the harsh reality is that a lot of tenants simply can’t afford it.’’

Rouleau now helps volunteer with the Tenants Union, which hosts a weekly help desk to help others who are also unsure if landlords are using illegal means to evict or force tenants out with the common tactic of remodeling the unit and raising the price to the newest market rate. She says volunteering with these other tenants has exposed her to rental horror stories even worse than her own.

“Predatory landlords and unchecked short-term rentals are strangling the city,” Rouleau said. “People cannot afford $4,000 to $9,000 a month in rent. A home that a friend rented a few years for $3,000 a month is now $12,000 a month. None of this is tenable. Who will teach in your schools? Who will work in your stores? What happens when homes are all occupied by visitors for a week?”

She said she has seen people from every working sector of Santa Barbara struggling with rent. And she worries that if short-term rentals are not addressed, and if the city doesn’t pursue a rental registry and rent control, “we’ll lose the people that are the heart and soul of this town for good.” (A rental registry would be an online service portal where property owners can register rental properties and update rental unit information, and the city can track real-time data on what landlords are charging. Housing advocates believe that a rental registry would allow more transparency as to what renters are actually paying each month.)

Dealing with the uncertainty and stress that comes with these scenarios can also weigh heavily on tenants’ mental and emotional well-being, Rouleau said.

“Having an unstable living situation is — and I don’t say this lightly — a mental-health crisis,” she said. “The toll this has taken on our mental health is incalculable, and our situation is exponentially better than many others. My anxiety is higher than it’s ever been. We do not know where we’ll go or how long we can justify this. It’s a crisis that lives in my head all day, every day. Where do you move when you don’t want to move? My friends and family are here. My roots are here. My home is here — but there’s no home for me here.”

One Bedroom, Family of Four (Plus a Dog)

Kristen Walker rents a one-bedroom apartment that she shares with her husband, their two daughters, and their 13-year-old dog — which she says has become a sticking point anytime her family has had to find a new rental.

“Even just being able to have the simple pleasure of having a pet, something that can be a huge emotional support, is, for the most part, now only a luxury afforded to homeowners,” Walker says. “It used to be that you could find something here if you tried hard enough — something below market, someone who would be kind enough to allow you to have a pet — but in our search, we’ve found that almost all rentals are controlled by property management companies who are strictly about profit and by and large never allow pets in rentals.”

The family splits the space, with the girls sleeping in the one bedroom and Walker and her husband sharing the living room. “We thought this would be a temporary situation, but it has gone on many more years than we would have liked,” she said.

She says most people who complain about the housing crisis focus on high rent prices alone, but she hopes that the community can become more aware of the impacts of pricing out the city’s labor force.

“I’ve noticed conversations about the lack of doctors, especially for women’s health, and lack of childcare options,” she said. “These are, at least in part, symptoms of housing unaffordability in our area.”

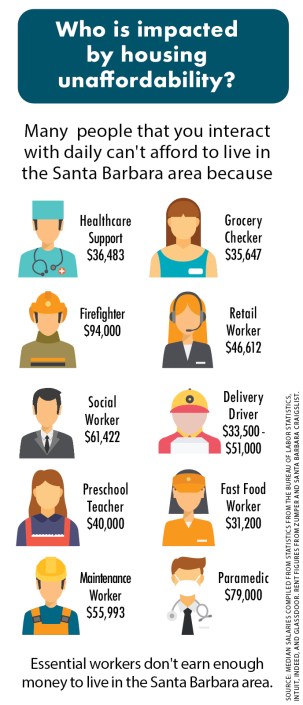

According to the most recent median salaries for the Santa Barbara workforce, health-care support workers ($36,483 per year), food service employees ($31,200-$35,647), delivery drivers ($33,500-$51,000), schoolteachers ($40,000), retail workers ($46,612), maintenance workers ($55,993), social workers ($61,422), paramedics ($79,000), and firefighters ($94,000) would all be considered “rent burdened” — or spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent.

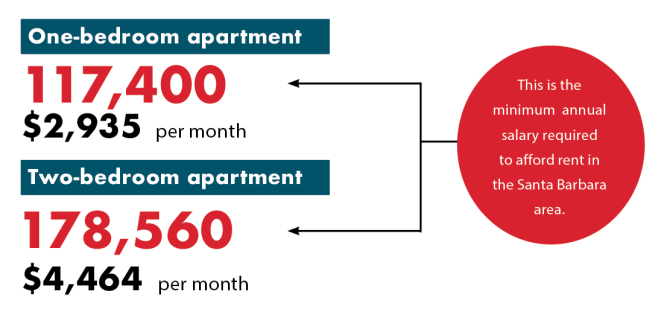

Most landlords require tenants to prove that they make three times the rent per month. By those standards, in order to afford the average $2,935 one-bedroom apartment in Santa Barbara today, applicants would have to make at least $117,400 a year. For a $4,464 two-bedroom apartment, the applicants would have to make $178,560.

So Santa Barbara’s workforce is slowly moving away, commuting from Lompoc, Santa Maria, Ventura, or Oxnard. Or they’re packing into smaller apartments, sharing bedrooms, splitting living rooms, and sleeping on pullout couches like the Walker family. In Isla Vista near UC Santa Barbara, students sleep two to three to a room, and still there are hundreds of other students scrambling to find housing each semester, sleeping in cars or stashed in hotels throughout Goleta.

“I’d love to see some people talk about solutions, like taxing vacant houses,” Walker said. “As we huddle up in a one-bedroom, I can’t tell you how many vacant homes I pass on my way to work. Those vacant houses represent people who are not living and working here, not volunteering in our local schools — like my husband and I do — and should be taxed at a much higher rate to shore up the empty hole they represent in our community.”

Optimism for the Future

Dick Flacks, a retired UCSB sociology professor and South County Co-President of SBCAN, is one of the loudest voices in the local fight for socially funded housing. Without a sustained, local source of funding, he doesn’t believe the city will ever meet the needs of its low- and moderate-income residents. And one of the best ways to accomplish that could be a number of new taxes funneled toward initiatives like the housing trust fund and the Housing Authority.

“The reliance on private development to do the job will not get us the affordable housing we need,” Flacks said. “Rental housing has to be subsidized.”

One of these options could be to increase the city’s transient occupancy tax — a tax imposed on guests staying at hotels, motels, or other commercial lodgings for less than 31 days — from 12 percent to 15 percent, he says, and use that 3 percent toward building affordable housing. Another would be to follow the example of Los Angeles and enforce a “mansion tax” on transfers of sales on properties over $5 million.

Either option would be another step toward addressing the housing crisis, he said, and with agencies like the Housing Authority being able to leverage city funding into more money to build 100 percent affordable housing, a little money can go a long way.

City leadership has already shown that it takes the problem seriously, by allocating surplus funds toward housing and by writing affordable housing into its goals in the upcoming Housing Element.

“I’m now more optimistic,” Flacks said. “Two years ago, housing wasn’t as big a deal.”

But it’s definitely a big deal now and at the forefront of discussion as the city tries to meet its need for affordable housing. Advocates are meeting with city leadership, urging them toward funding projects that would provide more than the 10 percent minimum affordable units that most private developers begrudgingly offer, and warming them to the once-far-fetched idea of passing rent control in Santa Barbara.

‘…it’s stupid not to realize we need some rent control.’

Economists and property managers balk at the idea of a rent cap, and Mayor Randy Rowse has been a vocal opponent to rent control anytime the issue is raised at City Hall, but tenants and advocates continue to bang the drum, and the council is now in a 3-3 split, with Councilmember Alejandra Gutierrez considered by many housing advocates as the swing vote that may tip the scales.

“Rent control enables people to stay in their apartments,” Flacks said. “Economists can’t argue with that; the data are clear. It doesn’t help people find apartments, it doesn’t increase supply, but I think it’s stupid not to realize we need some rent control.”

For many housing advocates, that leaves the city at a crossroads. If the soul of a city is in its people, then for Santa Barbara, it is in the unique mix of people who have landed here on the tip of the South Coast: the homegrown locals of every color and background; working-class first-generation Latino families; longtime business owners; transplants from all across the country; and Summer Solstice–celebrating, Fiesta-dancing, counter-culture-leaning SBCC and UCSB grads who found themselves in Santa Barbara for college and stayed forever.

If the only ones who can afford to live here are the wealthy, does Santa Barbara’s vibrant culture fade along with its workforce, and will it become another playground for the upper class, like the Hamptons? Where does that leave the rest?

For people who’ve already been priced out of town, like former S.B. High football coach Holguin, all that’s left to do for now is look forward to a future where they can once again afford to call Santa Barbara home.

“One day, I’ll be back in Santa Barbara,” Holguin said, “but for the time being, I’m going to ride this journey until my kids are done with high school. Sad to see what Santa Barbara has become.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.