Why So Many Creatures

Now Call Our Cities Home

UCSB Professor Peter Alagona’s Book ‘The Accidental Ecosystem’ Reveals Where the Wild Things Really Are

By Matt Kettmann | November 3, 2022

A few years ago, while riding his bike home from his job teaching the next generation of environmentalists at UCSB, Peter Alagona came across a bobcat on the path between Atascadero Creek and Hidden Oaks Golf Club. Up to that point, his academic life as an environmental historian revolved around endangered species, as detailed in his first book, After the Grizzly: Endangered Species and the Politics of Place in California, which was published nearly a decade ago.

After years of considering the elusive California condor, desert tortoise, and San Joaquin kit fox, the bobcat made Alagona curious about the wildlife that’s all around us, eating in our backyards, cruising our creekways, and sleeping in our parks. He dove into the burgeoning field of urban ecology, which analyzes, among other trends, how and why the animals we once considered so wild are now so comfortable in our cities.

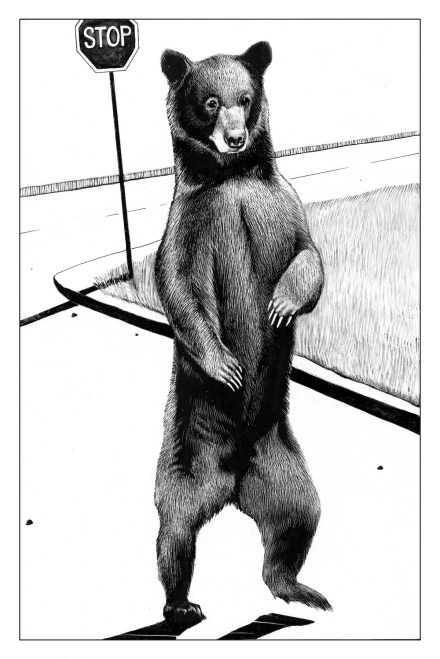

Last April, Alagona published the stories and studies that he discovered in urban areas across the United States as his second book, The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities. Written in a style that’s accessible to everyday readers but with the rigorous attention to detail demanded by academics, Alagona’s book examines everything from headline-grabbers like Malibu cougars, skyscraper-dwelling eagles, and bipedal black bears to innocuous yet important critters like gnatcatchers, raccoons, and house sparrows.

I’ve known Pete for more than 20 years now and have written about him for the Independent twice, about his endangered species book in 2014 and again in 2018 about his role as one of UCSB’s most popular professors. We caught up again this past June, soon after he’d returned from a trip to Tanzania, where he met with researchers from around the world working on the conservation of large carnivores. He was part of a team from California that’s seriously considering how best to reintroduce the grizzly bear to the Golden State, which is also the topic of his next book.

We talked a little about that and a lot about The Accidental Ecosystem, which features lessons for professional planners desiring more holistic cities as well as everyday city dwellers who simply enjoy seeing possums amble across their back fence. What follows is a condensed and streamlined version of our conversation.

How did this book come about? I spent the first decade or so of my career focusing on endangered species. Most of those creatures are animals that, by definition, you almost never see. Most are creatures that people fight about a lot politically, but they don’t come into contact with in their lives with any regularity.

Then I became aware that this field of urban ecology was producing fascinating studies on urban wildlife and people’s interaction with it. It told me that there was a story to follow, and I spent the next several years figuring out how to tell it.

You certainly do cover the American map, with chapters covering bats in Austin, coyotes in Chicago, cougars in Los Angeles, bald eagles in Pittsburgh, and even gophers at Bushwood Country Club, among others. I’ve lived in big and small cities my whole life, and in all of those places, there are stories of increasing numbers and diversity of wildlife over the past few decades. Although the story in each place is a little different — the species are different, or the timing, or the geography is different — overall, if you put them together, there is this trend over time.

The crazy thing is that this increase in wildlife in cities is not something that would have been predicted by the ecological theory that was out there. It came as a surprise to people that this happened. Only recently are we figuring out why this has happened, and it challenges some basic assumptions in conservation.

Is Santa Barbara a hotbed for this? We are incredibly fortunate here to be surrounded by all these ecosystems and natural areas. But many cities, including some of the biggest cities in the United States, like New York, were built in places that were unusually biologically diverse and productive before the city was built. We’ve destroyed a lot, but many cities remain places where wild creatures naturally return. So Santa Barbara is an example of this, but I wouldn’t say it’s unique.

You write about birds being one of the most familiar forms of urban wildlife and discuss unique challenges that they face, such as bird feeders and cats. So should we kill all the house cats? You put your finger on the most controversial thing in the book. I just want to be clear that I really like cats. I’m an animal person. I have a lot of pets. But you know what I don’t own? A cat. The reason is that I live in Santa Barbara and my doors and windows are wide open all the time. I believe cats should be kept indoors. It’s better for the cats. They will live longer and have healthier lives.

When cats wander outside, there are consequences. They carry diseases that can be passed on to other animals — including people — and cats are efficient exotic predators. They kill a billion small animals every year in the U.S. alone, including birds, reptiles, and small mammals. Some are creatures we don’t want, like mice and rats, but a lot of native wildlife are victims, too. Anyone who loves both wildlife and cats should support keeping them apart.

I love cats, but I strongly believe that all the evidence suggests that cats should be indoor pets. When your cat’s outside, you’re introducing an exotic apex predator into the ecosystem, and that’s gonna have a lot of consequences.

This is also related to the book’s broad theme of the accidental ecosystem, where we’ve built cities that didn’t account for the creatures around us. I advocate moving from an accidental to a much more intentional urban ecosystem. What are the kinds of environments we can create that are more conducive for wildlife, people, and domesticated animals?

And what’s so bad about the bird feeder? Bird feeding can best be understood as a giant, crowdsourced experiment in wildlife management. It creates winners and losers. Some species or individuals benefit from it; some get drawn in and it becomes a crutch or even a trap. If you’re attached to your bird feeder, then, at the very least, you should commit to consistency and cleanliness. Bird feeders can be petri dishes for salmonella, and that’s something no one — including a bird — wants.

The book looks at how public perception changes over time. Eagles were once considered pests, and now people are okay if they snag a kitten or two because they appreciate their comeback. What explains that shift? You hit on something really important. In the 21st century’s human-dominated ecosystems, the ability of species to survive is, in many cases, directly related to people’s willingness to tolerate them. There’s a whole field of social science research on this issue of human tolerance for wildlife and what affects that.

Tolerance is related to people’s interests, but also their values. Interests can change quickly, but values, which are formed in youth, usually don’t. Generations change, but individuals less so. That said, values toward wildlife have changed significantly over the last several generations, due to a range of forces including urbanization. In urban areas, people are more likely to be tolerant of wildlife if they have some educational background. This is a complex equation, but we are slowly moving toward a point where more and more people see wildlife in their communities not just as potential threats but as posing potential benefits and even opportunities.

In Santa Barbara, people and institutions, including UCSB, dump a lot of poison into the environment to manage rodents regarded as pests. That doesn’t help over time, because rodents reproduce quickly, evolve tolerance, and often pass on these toxins to other, so-called non-target species, like bobcats.

Maybe if we want fewer rats, we should have more owls and raptors, and we shouldn’t be putting blood thinner into the environment. There are smarter and more humane ways to accomplish these goals.

You explain how the decline of hunting, which once helped pay for conservation, is contributing to the rise of urban wildlife. What is hunting’s role in the modern equation? Hunting has been at the center of wildlife conservation in the United States for more than 100 years. The concept is that you want a managed, sustainable population of wildlife for human use, either for sustenance or recreation or other ecological services. Hunting and fishing fees then help to pay for conservation. This model is on the decline, however, for two reasons: Hunting is not helpful as a management strategy around urban and suburban areas where it would be dangerous. And culturally, it is declining as a recreational activity. Hunting has a high barrier to entry, and when it isn’t a part of your family’s core culture and identity, it tends to wane over generations.

We need a new set of tools. Hunting probably still has a place in many areas, but it’s no longer a one-stop shop or cure-all for dealing with wildlife management.

How should urban areas be dealing with wildlife management? I recommend two approaches: Individually, people can start to think more about how everything they do in their communities, from how they garden to how they drive, affects wildlife. In communities, one of the best things we can do is start to think in more focused ways about how to integrate wildlife into every aspect of county general plans, from parks to transportation to education and housing. Wild creatures tie all of these elements together and help you think holistically about the general habitat you’re creating for people.

Some communities, like Boulder, are already doing this. But there are other cities like Chicago that are trying to think about wildlife corridors and the urban-wildlands interface too. There are also marquee projects, like the Annenberg Crossing in Ventura County, which is trying to create connectivity between the wildland areas in an enormous urban region by providing passage over the 101 freeway. Even the landscapes that are the most fragmented and most affected by humans can be pieced together in creative ways to allow animals to circulate through and thrive in these areas.

The city of Philadelphia had an incident one morning where thousands of dead birds were on the streets when people got up for work. They had collided into a skyscraper overnight during their fall migration. This happens a lot, but it doesn’t get a lot of attention.

So Philadelphia started a voluntary program, but one with a lot of buy-in, during those fall and spring migrations up the Atlantic flyway to reduce city light in a way that reduces bird collisions. You wouldn’t expect this in Philadelphia, but these are some of the little things that can be in your city or your county that can make a big difference for animals that are passing through.

Taking these measures proactively will make our communities more livable, reduce carnage, increase thriving, and move us closer to the goal of intentional urban ecosystems.

Would you say that our fates as humans are intertwined with our wildlife neighbors? That’s exactly right. We are used to thinking of animals as resources or pests when, in fact, we benefit a lot from seeing them as members of our community. We share space. We share resources. We share habits. Sometimes we even share disease. These are all things that affect us in ways that are hard for the average person to see on a daily basis. But they’re real. The more we’re intentional about urban wildlife, the better we’re all going to be.

It certainly feels like most of us are rooting for them at this point. When you see a creature that you don’t expect to see, we all know what that’s like. There’s a moment of surprise and wonder and you suddenly see the place where you live differently.

Just a couple weeks ago, I was out late in the evening, and close to my house, I saw a fox run across the road. That’s not too unusual — people see foxes all the time.

But I just remember that moment of being like, “Oh yeah, I’m sharing this space with these creatures that I never see, but they’re out there, making a living in my community just like I’m trying to do, and they’re doing their best to coexist with people in a densely populated space with lots of resources but also lots of hazards.” I respect that and I value that and it makes my life a little bit better to know they’re put there. It gives me perspective.

Last but in no way least, are you still actively working on reintroducing grizzly bears to California? I wouldn’t say that we’re reintroducing grizzlies, since there are no plans to do so. But along with wonderful colleagues at UCSB and beyond, I’ve been working hard to advance the research on that front. We now know much more about California grizzlies, even though they’ve been gone for almost a century, than ever before. With that knowledge, of course, comes the question of what it would take to bring them back. I would leave that mainly to the policy makers, but what I can say is that 2024 is the 100th anniversary of their presumed disappearance in our state. It’s going to be an opportunity to talk a lot more about the past, and also the future.

What would be the ideal space? Grizzlies didn’t disappear from California due to habitat loss. They disappeared due to persecution during a time when most people had very different values than today, and when there were few conservation laws.

Even now, there’s still probably plenty of habitat available to support a modest population of grizzlies in California — much more so than in places like Greece and Spain, where their close relatives still live today — as evidenced by our more than 35,000 black bears. There are something like 12 times as many brown (grizzly) bears in Europe as there are in the lower 48 U.S. states.

So bringing them back is clearly not impossible. It would involve risks, benefits, hard work, and a long process. But ultimately, like most other wildlife issues, it would just be a choice that we, as a society, could make. For almost a century, we’ve been making one choice. Maybe at some point in the future, we’ll make a different one.

See peteralagona.com to buy the book and learn more. For info on the grizzly bear reintroduction movement, see calgrizzly.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.