Historical Museum

Explores Santa Barbara’s

Bohemian Rhapsody

Mountain Drive, Still Alive

By Nick Welsh | October 6, 2022

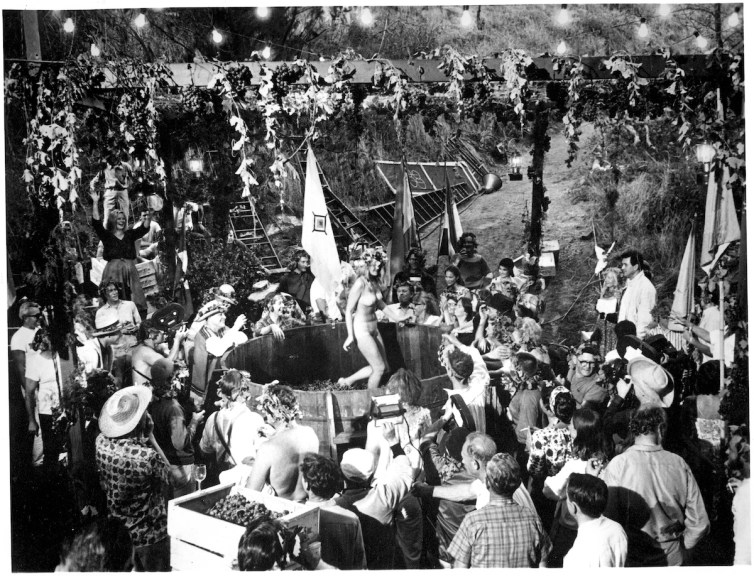

To the extent Mountain Drive’s exuberant experiment in Bohemian living still remains lodged on Santa Barbara’s historical horizon, it’s as the orgy — Hot tubs! Wine stomps! Naked people! — most of us never got invited to. But when Chris Ervin took over as archivist of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum nearly four years ago — fresh off the boat from Orange County — he’d never even heard of Mountain Drive, the 50-acre utopian society of creative non-conformists that flourished here between the late 1940s and the early 1970s.

Ervin’s “Eureka!” moment came when the granddaughter of a Mountain Drive settler called, asking to hear her grandmother’s oral history. Ervin quickly discovered there was not just one oral history in storage but a whole box of Mountain Drive oral histories totaling about 30 hours. “It jumped out at me as something special,” he said. “It hit me in the face.” At the same time, higher-ups within the museum — better known for its ultra-traditional approach to local history — had been encouraging Ervin to try something edgier. With this unexpected find, he was only too happy to oblige. Out of all this has come the exhibit opening at the museum October 6, bringing the much-mythologized Mountain Drive community — off the grid before there was even a grid to be off of — back from the ashes out of which it sprang.

The guiding hand behind Mountain Drive was Bobby Hyde, a writer and utopian experimenter who extolled the virtues of living in and with nature with a passion bordering on the erotic. Hyde bought the land — then 50 acres of fire-charred chaparral — for a song in 1940. After World War II, he and his wife and co-conspirator, Floppy Hyde, began looking for like-minded spirits who might fit into the brave new world they had in mind. Hyde connected with GIs returning from World War II who were enrolling in classes at Santa Barbara College, then located on the Riviera. Those with whom he clicked were offered one-acre lots for unheard-of-low down payments of $50, coupled with $50-a-month payments whenever they could afford them. Hyde — who described himself as a sculptor whose tool was a bulldozer — also offered to teach his new neighbors how to make adobe bricks and how to build improvised housing using those bricks in combination with salvaged building materials.

Before all was done, about 40 structures would pop up from that steep and rugged landscape. But much more than makeshift homes — there were no building codes yet to constrain their inventive notions of housing — the Hydes set out to create a whole different culture. The Mountain Drivers, as they came to be known, were competent, creative, educated, self-reliant, independent-thinking people. Many were artists. Many had seen action in the war. One — an optometrist with an office in town — was a former fighter pilot. He would design experimental aircraft upon his return. Later, he would also emerge as an evangelical champion of psychedelics.

Another vet had been stationed in Berlin, working for military intelligence. That cultural exposure would change him forever, and he would seek to pay that forward by making wine on Mountain Drive and devising multiple festivities to be celebrated with a maximum of libation and hedonistic abandon.

Famously, there were the grape-stomps with their grape-stomp queens — no clothes involved. There was Bastille Day to celebrate, as well as the birthday of Scottish poet Robert Burns, where haggis was served accompanied by as many bagpipers as could be cajoled. There were Renaissance Faires, cultural precursors to the Summer Solstice festival. There were the famous Mountain Drive Pot Wars — dueling potters competing with each other — that drew such large crowds (3,000 people!) that the fire department felt the need to cancel the event in 1967. Music was everywhere; the drum circle was born on Mountain Drive and a homespun hybrid known as “browngrass” — reflecting the primary color of local vegetation — evolved for those more inclined to picking and fiddling. While not overtly political, Mountain Drivers relished satirical warfare, creating what was known as “The Jack Ash Society” to do battle with the John Birch Society of the early 1960s. The Jack Ashers boasted, for example, of stopping the instruction of the Eskimo language in local schools and of keeping whale blubber out of local butcher shops.

Mountain Drive was, to be clear, a fantasy fueled for, of, and by the male imagination. Women were to be barefoot and pregnant or in the kitchen baking bread while the all-male members of the “Sunset Club” congregated to discuss the weighty issues of the day and, of course, drink. And they drank a lot. There was an “over the banks” club for residents who drove their cars over the side of the road after perhaps imbibing too much Pagan wine. The emotional hangovers experienced by children of alcoholics, however, are well-known and far more lasting than the hangovers their parents reckoned with. That was certainly the case for many of the children of the original Mountain Drivers. And for teenage girls, the experience of getting groped by drunk older men at a grape-stomp was notably less enjoyable than it was for those doing the groping.

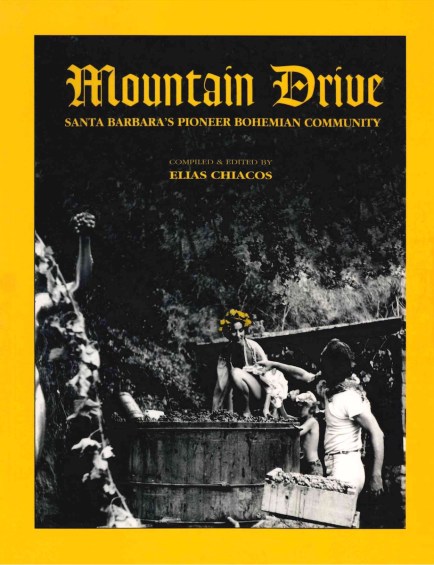

Ervin teamed up with Elias “Lee” Chiacos, who in 1994 wrote what’s still the definitive book on the Mountain Drive experience (Mountain Drive: Santa Barbara’s Pioneer Bohemian Community). Ervin had his gold mine’s worth of oral histories, but no photographs. Chiacos had tons. Somehow, they managed to select 50 for the Memories of Mountain Drive exhibit.

For Ervin, the exhibit reflects more than Santa Barbara’s abiding hospitality for communities determined to remain off the beaten path. (Santa Barbara’s Hobo Jungle, the Sunburst community, and the short-lived Monarchy of Christania all come to mind.) Ervin sees it more as a compelling lens through which to view World War II’s impact on Santa Barbara. “A lot of these people were dealing with PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] before there was such a thing as PTSD,” he commented. “They’d gone to Europe and came back determined to live life on their terms and not some buttoned-down, conservative, by-the-numbers lifestyle. This is how they dealt with it.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.