What Will a Wildlife Crossing in Gaviota Look Like?

Large Stakeholder Group Meets to Start Study Process

Wide bridges that mimic grasslands and tall tunnels of corrugated steel have saved countless wild animals in places where their habitat is bisected by highways and the 3,500-pound vehicles that use them. California’s first wildlife crossing, along Tahoe National Forest’s Highway 89, lowered the number of animals killed there from 29 in one decade to five in the following seven years. Caltrans and a large group of stakeholders hope to do the same in the Gaviota Pass area of Santa Barbara County.

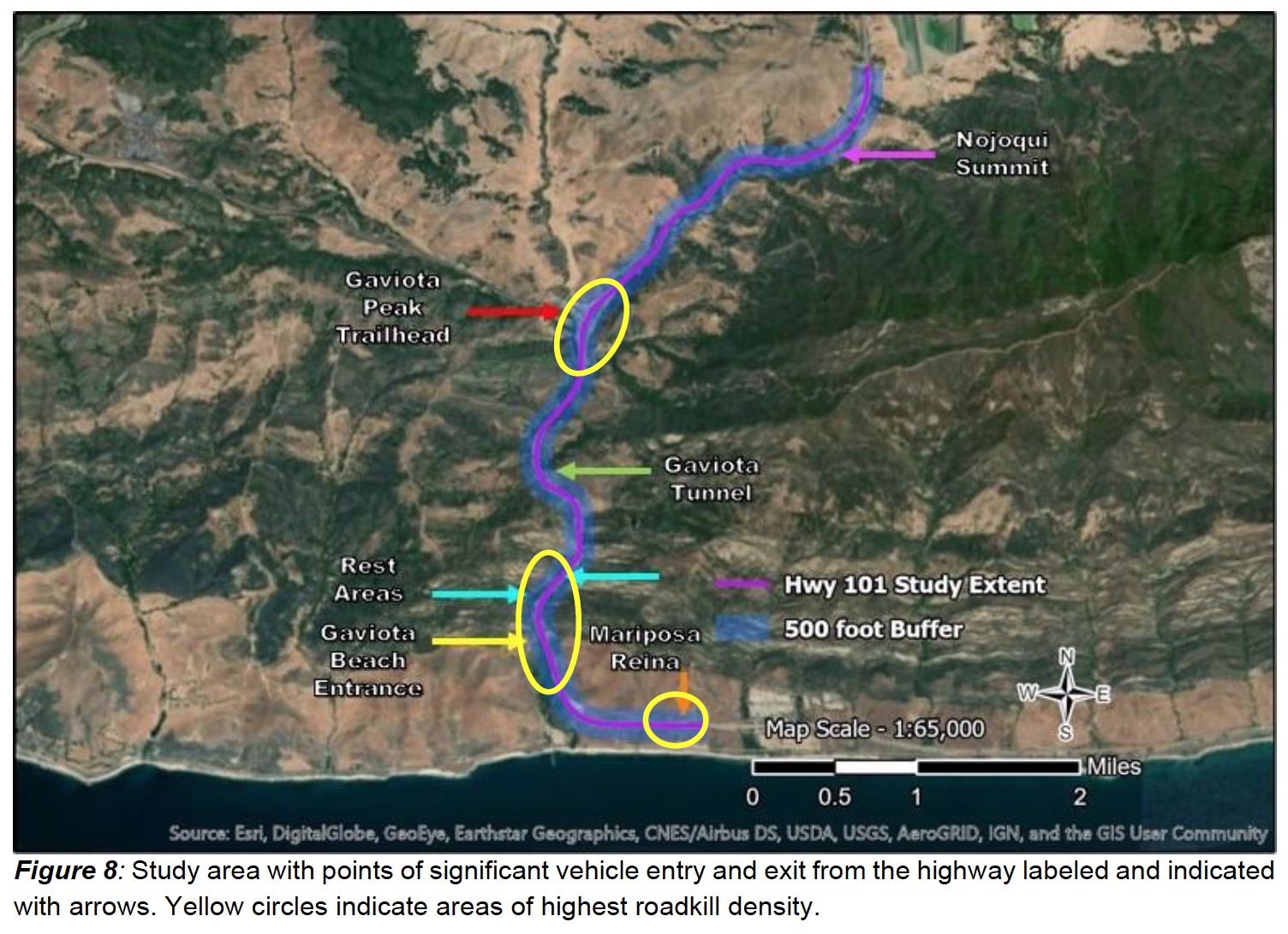

About 29 people from nonprofits and state and county agencies met on December 2 to discuss the start of a year-long study of a six-mile area from the Nojoqui Grade to Mariposa Reina. Among the stakeholders was Joan Hartmann, supervisor for the county’s 3rd District, where the Gaviota Coast is found. She recalled thinking a freeway structure made for wildlife was such a strange thing but said of the meeting: “There really is a science of road ecology, and there really are a whole variety of interventions that work to better protect and guide animals.”

An independent scientific consultant unaffiliated with Caltrans was being hired, project planner John Olejnik emphasized, who are experts in wildlife-corridor studies: ICF/Jones & Stokes. “We’re paying for it,” Olejnik said, of the $327,000 the study will cost Caltrans, “and we’ll be really glad to take the results. We’ll use that to decide, collectively as a group, how to work together to implement the results.”

Landowners in the area are an important part of the stakeholders, Olejnik said, because an animal crossing might require land Caltrans doesn’t control. “It’s not always a fence or a bear culvert or a ramp,” he said. “It might be land preservation that accomplishes this. Or, if things are built too close to the highway, that may constrain what we can do.”

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

One of the groups involved, the Coastal Ranches Conservancy, has a good idea of where crossings should be built. The nonprofit funded a study by UC Santa Barbara’s Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration that looked at the past 60 years of data for that same six-mile stretch. Finalized in January 2020, the Gaviota study showed that cars took their toll on amphibians, reptiles, birds, and insects, but it was mammals that were either recorded or killed the most. Mule deer led the list, followed by the California vole, gray fox, raccoon, and mountain lion. Three places in particular stood out: Mariposa Reina, the highway rest areas and the Gaviota Tunnel, and the intersection of highways 101 and 1. The last two are where two mountain lions and a bear were hit by cars and died last summer, both apex predators that have home ranges as large as 50-150 square miles.

As well as the horror of hitting a large animal, drivers face personal and financial injuries: Hitting a deer cost more than $8,000 on average, a University of Montana study found, and in the more than one million such incidents every year, 200 people die nationwide.

Though Caltrans is footing the study cost, funding to build whatever the study and stakeholders recommend is an open question. The largest animal bridge in the world is being built in the Agoura Hills, an $87 million overpass that will span 10 lanes of the 101 to provide a 200-foot-long, 165-foot-wide passage for endangered mountain lions and other species of the Santa Monica Mountains. The National Wildlife Federation raised $72 million for the overpass in a near-decade of fundraising. In Santa Cruz County, Caltrans is building a 60-foot bridge and tunnel for large animals along a deadly part of Highway 17. The $12 million Laurel Curve project included $2 million raised by the county’s Land Trust, which gained conservation easements for 460 acres in the nearby mountains, $4.5 million from the state, and $4 million in a local transportation tax.

Supervisor Joan Hartmann gave the Coastal Ranches Conservancy and the Gaviota Coast Conservancy full credit for appealing the original 101 culvert project that got this ball rolling. “As in everything for Caltrans, they have to study it, follow a sequence of steps, and go through the process,” she said. But in a year’s time, “there will be so much money for infrastructure,” Hartmann noted of the new federal act, which holds $350 million for exactly this purpose.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.