Celebrating the Birth of Surfing in California

Shaper Renny Yater, Artist John Comer, and Others Showcase History at the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum

By Ethan Stewart | July 1, 2021

It is just past 8:30 on Monday morning, a time of day and week that typically offers a reckoning of some sort. The phone rings once. Twice.

I start considering the absurdity of my task: cold-calling a man in his 90th year on the planet on his “work phone” before 9 a.m. on a Monday. There is no way he is answering.

But, before the third ring is done, the line clicks and a voice picks up, strong and clear with a touch of gravel: “Morning. Yater Surfboards.” There is no feigned pleasantry in the greeting. Zero bullshit.

I know immediately who I am speaking with, but respect demands a certain tact. Inquiring about the man who has been commercially shaping surfboards longer than anyone else alive, I ask, “Is Reynolds Yater there, please?”

A simple “Yeah” fires back at me, landing like a challenge. It is followed by an extended silence that speaks volumes — there is no room for pomp in this exchange; there is work to be done.

Legends Honoring Legends

A historic art show is currently hanging on the walls of the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum. Just a stone’s throw from the still waters of the harbor, the lifeblood of a sport and the underpinnings of a culture have been laid bare for all to celebrate. It is the origin story of surfing in California. Told by foam and fiberglass and paint, it is also the story of how modern beach culture was born along our coast. Indeed, there would be no beach blanket bingo as we currently know it if not for the pioneering misfits that first started sliding waves more than a century ago on our side of the Pacific.

Nearly 15 years in the making, the show, officially titled Heritage, Craft & Evolution: Surfboard Design 1885-1959, is a collaboration of the highest order among a small group of aged surfers, all of whom happen to be world-class artists. At the helm of the effort is Santa Barbara’s Reynolds Yater, a man uniquely prepared for the task.

“The point of this whole thing is to give respect to those who made the sport of surfing what it is today, to honor the people that were there in the beginning,” explains Yater. “Surfing created the beach culture in California, but I’m not sure young surfers today know that. It’s important to remember how that happened.”

To be clear, Yater, known ubiquitously as “Renny,” is an undeniable legend in the surf world. His bona fides are peerless at this point, with a résumé that directly connects the nascent days of the once-fringe sport to the billion-dollar and beloved mainstream industry that it has become today.

Born in Los Angeles in 1932, Yater has been “doing stuff with surfboards since I was in diapers.” His first board was a used 10-foot wooden plank weighing over 75 pounds, ridden in the shorebreak at Doheny State Park when there were roughly 100 surfers in the entire state. In the 1950s, Yater was an early employee of Hobie Alter and, later, Dale Velzy, two of biggest — and the first — commercial surfboard builders in the United States.

Yater relocated to Santa Barbara in 1959 and has called it home ever since. Something about our collection of cobblestoned, right-hand point breaks will do that to a regular foot. The fishing in the channel was equally magnetic for the young man from Laguna Beach.

Yater Surfboards opened its doors that same year on Anacapa Street but bounced around in the decades since, making stops in Summerland as well as on State Street, Gutierrez Street, and Gray Avenue. Models like the Yater Spoon, the Pocket Rocket, and the Nose Specializer made Yater a sought-after shaper for many of the world’s best during the halcyon days of the sport in the 1960s and ’70s. Regular customers included royalty of the sport, including Miki Dora, Joey Cabell, Kemp Auberg, John Severson, and Bruce Brown. A Yater board, and one of his Santa Barbara Surf Shop logo T-shirts, famously made an appearance in the film Apocalypse Now thanks to Robert Duvall’s character.

Now in his 10th decade of life, Yater still shapes custom surfboards for customers who know the timeless value in getting a board from a master. The wait list is long. Yater started shaping before the advent of electric hand-tools and now works in the age of boards shaped more by computer software than by human hand. He has worked with all manner of wood and foam and has had a front-row seat for every change, big or small, in surfboard design from the very beginning. His life story has run concurrently with the story of surfing. There aren’t many left who can say the same. In fact, there might not be any at all.

Origins of an Art Show

As originally conceived, Heritage, Craft & Evolution was an art show meant for another time and place. In the early 2000s, Yater partnered with a relatively underground fine artist named Kevin Ancell to make a series of high-end, balsa-wood surfboards laminated with abalone inlays in the fiberglass. Ancell was a rough-around-the-edges character from the extended surf world with some major league art chops.

From oil paintings to sculptures and wood carving, Ancell’s art runs along a diverse spectrum that is all its own. A hyperrealistic and heavily symbolic oil painting of Jesus healing the kooks of the world slots in right next to a robotic mannequin hula dancer with a machine gun. He is a weird wizard of his own making, and his collab with Yater was exceptionally potent. Their first show in West Los Angeles sold all eight boards that they offered, each one going for many thousands of dollars.

“That was a rewarding experience for me on a lot of levels,” recalled Yater. “We really stumbled onto something.”

The duo set to thinking about what they might do next together, deciding to make more collectible, art-minded surfboards. They wanted to celebrate the “wood era” of surfing in California, when redwood, pine, and balsa boards were the norm — a time when surfing-as-industry was a laughable notion. They wanted to follow the evolution of the sport in California from its introduction in 1895 through to the end of World War II via the lens of surfboard design and specific surf spots that made it all possible.

Ancell suggested that they bring in a third artist to fully realize the concept, a plein-air painter with roots in the 805 named John Comer. The idea was to have Comer come into the board-making process and paint landscapes of specific surf breaks on the boards to better capture the moments being celebrated. Yater was in full support, so the seeds were sown for an exhibit that, unbeknownst to them at the time, wouldn’t bloom until nearly two decades later.

“I was stoked just to be asked,” said Comer of his role. A longtime member of Santa Barbara’s fabled Oak Group and former studio mate of the late Ray Strong, Comer, who currently has a solo show hanging at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, has been friends with Yater for the better part of the last 50 years. He even worked a few seasons on Yater’s commercial fishing boat back in the day.

“Both those guys are experts at what they do,” said Comer. “As soon as they explained the idea to me, I was in.”

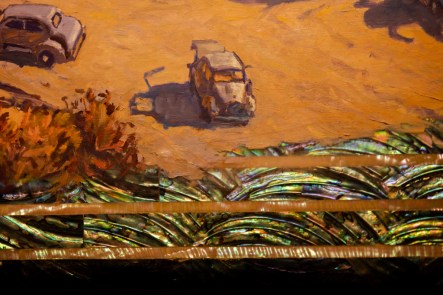

The plan was to build out a collection of boards, each shaped by Yater to match the style of the moment being remembered. Ancell would then use paint to painstakingly transform the white foam into visually exact replicas of whatever wood material the boards were originally shaped in, at which time Comer would paint a landscape on the deck, memorializing a specific surf break.

The first three created offered quite an introduction to the eventual eight-board collection: an early 1930s Tom Blake paddleboard with faux redwood and metal rails and a vignette oil on gesso painting of Palos Verdes Cove; a 10′6″ Pacific System Homes faux balsa board with abalone inlays from the early 1930s with a painting of the lineup at San Onofre; and an early 1950s Hobie Balsa Board with Dana Point on the deck. They generated immediate buzz, the trio’s combined skills proving almost too good to be believed.

“I remember going down to the Laguna Art Museum and showing those first boards to some of the staff,” said Comer. “We pulled one out of a bag, and they were just stunned. They couldn’t believe it wasn’t real balsa wood. I mean, jaws dropped.” An opening was booked for the following year to run in tandem with a retrospective on illustrator Rick Griffin’s career.

But fate had different plans. The economy cratered in 2008, putting the project largely on hold, and both Ancell and Comer ran into life challenges for wholly different reasons. The trio opted to cancel the Laguna show.

But Yater kept shaping the remainder of the collection to hold up his end of the deal. “It was easy for me to continue. It became natural,” said Yater. “I lived through these board designs and had ridden and shaped them all before at some point, so I enjoyed going back.”

But without his two partners in crime, the project eddied out in that liminal space where so many ambitious projects go to die. “Everything just sort of stopped,” said Comer. “We all went on to other things.” The boards began collecting dust.

Revival Time

The resurrection began a few years back when Comer’s partner, Suzette Curtis, started pushing John to bring the project back to life. A designer by trade and former art director at Patagonia and Islands magazine, Curtis recognized that the trio’s project was special.

After Ancell opted out of the hopeful revival, Yater and Comer recruited another surf-world artisan, Peter St. Pierre, to help them finish the collection. A maestro with the airbrush, St. Pierre stepped in to reprise Ancell’s role, albeit with his own personal flair, turning Yater’s foam shapes into replica wood planks and balsa decks. Comer then took all the boards south of the border to his studio in Baja and finished the collection, painting scenes like George Freeth at Redondo Beach, the Kawananakoa Brothers at the San Lorenzo Rivermouth in Santa Cruz, and Bob Simmons at Rincon.

Once the nine-piece Heritage Collection was complete — comprising seven boards and two paintings — Comer and Yater also made the “Channel Collection,” featuring plein-air paintings on wall-mounted surfboards of Santa Barbara–specific touchstones such as Refugio, Rincon, El Capitan, and Point Conception. Not only had the original idea been saved and finished, but it had become more impressive in the process. In fact, there was even a beautifully done, perfect-bound 40-page book to go with it, thanks to Curtis. It was time to show the world.

Plans for the current show at the Maritime Museum began to take shape in the months before COVID hit. Passing on the opportunity to open their show in Santa Cruz and San Diego, Comer and Yater needed the right spot to honor this truly unique thing they had done.

“It was tricky to find a gallery that fit,” said Comer. “This is not just an art project. And it’s not just a history project. It requires a certain amount of respect.”

When they stepped into the Maritime Museum, they knew they had found the spot. And after nearly 15 years of waiting, not even a pandemic could stop them.

“Surfing has given me a lot in life. When I started out all those years ago, we had no idea where it was going — none of us did,” explained Yater with a very matter-of-fact wistfulness. “It’s nice to give back to the tradition and honor how it began here in California.”

411 | Heritage, Craft & Evolution: Surfboard Design 1895-1959 is on display at the Santa Maritime Museum, 113 Harbor Way, Suite 190, from now through October 30. Call (805) 962-8404 or see sbmm.org.

You must be logged in to post a comment.