Santa Barbara Students Struggle

to Learn During Pandemic

Teaching Virtually Has Not Been Working Well for all Elementary Grades

By Delaney Smith | Photos by Daniel Dreifuss | February 18, 2021

When they finally returned to school, some of the students couldn’t even write their own names.

Others struggled to use scissors or hold pencils.

For Carpinteria’s Canalino kindergarten teacher Andrea Edmondson, this was the reality when her students returned to the classroom in October.

The COVID-19 pandemic devastated, destroyed, and took lives. But the impact of the virus on schoolchildren may be the most insidious impact of all.

A generation of students, those who were already struggling to keep pace, have fallen further behind, and it will likely take years before the true impact of distance learning is fully known.

For educators, trying to minimize what’s now known widely as “learning loss” has proved to be the educational challenge of their lifetime.

For students, it’s a new way of life.

The Independent spent weeks interviewing teachers, students, and education activists to better understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the state of education. The experiences vary, but one thing is clear: Children will never be the same.

When her students returned to class this fall, after months of virtual teaching in 2020, Edmonson saw the effects of learning loss firsthand. She estimated that half the class was struggling and behind, while those who were English learners struggled the most.

Not surprisingly, students who had resources and support at home tended to succeed better than those who didn’t have space to do schoolwork or whose parents had to work and couldn’t be home to help. As a result, learning loss has widened the achievement gap between the haves and have-nots even more dramatically than it was before.

According to a December 2020 study released by McKinsey & Company, U.S students are likely to have suffered up to nine months of learning loss in math, on average, by the end of the academic year because of pandemic distance learning. Students of color could be as many as 12 months behind. The study concluded: “While all students are suffering, those who came into the pandemic with the fewest academic opportunities are on track to exit with the greatest learning loss.”

Educators, parents, students, and the whole community has taken the challenge head-on.

Local school districts are working to mitigate learning loss in a variety of unique ways — from changing the grading system to opening a summer school program to relying on professional learning communities, creating learning centers, and more.

Carpinteria Unified School District

Carpinteria Unified was one of the few in the district to be allowed to reopen its elementary schools this fall. They received permission from the State Board of Education to begin a hybrid model of in-person instruction, meaning the students in each class were split into cohorts and brought back into the classroom two days a week and worked online at home three days a week. This has made for a massive turnaround in student performance.

Kindergarten teacher Edmonson even saw the change in her new-to-school kindergarteners. The first few months of the school year, she only knew her students through a computer screen. When the district switched to a hybrid format last October, she was with her class face-to-face.

Now she was able to understand how to motivate each child. When one middle-income, English-speaking student entered class only knowing how to write his name, she had to find a way to engage him. “I discovered he was really into trucks. I used that to motivate him, and now he’s totally on track to where he should be.”

Kristina Garcia, who teaches a 4th grade and 5th grade combination class at Canalino, has seen the effects full circle. (In combination classes, students from two grade levels are placed in one classroom under the same teacher.) Last year Garcia had to teach her 4th grade students remotely. Now those same students are in her 5th grade class, where she can teach them in person.

Carpinteria Unified is nearly 75 percent Latino, and many of the parents work in the marijuana and flower industry and are unable to be home with their children. Garcia said that computers and Wi-Fi were a huge barrier, as well, despite the district handing out devices and hotspots. The biggest issue, though, came down to a lack of accountability and motivation. Even though she brought in counselors and did home visits, some students would not do much of anything online. “It was like pulling teeth to get them to interact,” she said.

But things have really turned around since Garcia began teaching her students face-to-face twice a week. One of her 4th graders last year was really struggling, so much so that Garcia had trouble reading his writing. Now, in her 5th grade class, the student can write a solid paragraph. “He’s up two grade levels from where he was,” she said.

Garcia has learned through assessments that students were “all over the place” and that she couldn’t give them the same assignments. Approaching each child’s needs individually has been her biggest tool against learning loss. Assignments are focused on specific students’ level of learning. The classroom aide has been a great help working with each student.

“I’ve been teaching for 23 years, and this has been the most challenging year because of how hard it is to differentiate instruction,” said 2nd-grade dual-language teacher Sonia Aguila-Gonzalez. “I have students reading five words per minute and others 100 per minute,” she said, but because students must sit six feet apart, it’s not possible to have them working closely with each other.

Aguila-Gonzalez said that although some of her students are behind, distance learning wasn’t all bad. “They can join Zoom, they can use Flipgrid, Powerpoint, Google Classroom. All of that is useful when they grow up. They have learned a lot about gratitude and being resilient.”

But this isn’t always true, especially for young learners. Jessica Clark, a mother of two children in Canalino, said though her oldest child was doing well with distance teaching, her younger, 5-year-old son, Dax, was experiencing Zoom fatigue.

His mother had to sit next to him through the whole Zoom class because it was so difficult to make him pay attention. “He hated school even though he had always loved prekindergarten. He would cry and cry and cry every time it was time for Zoom. Once we were given the green light for hybrid, it was like a night-and-day difference.”

Carpinteria Unified counselors Bert Dannenberg and Shanna Hargett said that the emotional toll caused by distance learning is to be expected. When kids were stuck on Zoom, they felt the strain not just of academic loss, but also of being separated from their friends and teachers. Even the hybrid classes are not perfect.

“They can’t really play together,” Dannenberg said. “They can’t use the same balls on the playground or touch the same equipment. A lot of the social-emotional impacts we’re not going to fully see right away, but we will see over the next three to four years. Some of these kids have already missed a ton of school between the fires, debris flow, and now pandemic. The effects will be felt down the road.”

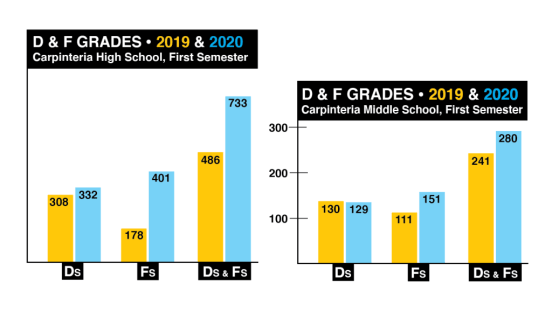

Grades are one way to illustrate the impacts of learning loss in Carpinteria Unified. The district did not give elementary grades when it went remote, but it could provide middle school and high school grades to demonstrate learning loss.

Jaime Persoon, principal of Canalino School, said, “On a typical year, there’s multiple interruptions throughout the day like band, art, therapy, PE.” But on the hybrid model, there are no interruptions. “Those kids are with their certificated teacher the entire day, and there’s no interruptions.” Teachers use the days students are learning remotely to teach art and other enrichment subjects.

Structuring the day this way, Peterson said, allows for the most impactful learning because instructional days are shorter and teachers from all grade levels are able to meet together to discuss a student’s progress across grade levels. This has really helped students get back up to speed. “We’re seeing huge strides,” she said. “The kids are absolutely thrilled to be back.

Goleta Union School District

Goleta Union tends to be an outlier among other school districts because, despite its distance-only learning model, it has shown the least amount of learning loss among its elementary students. Although its Latino students have suffered the most, they have had less leaning loss than students of color in any other district.

Goleta Union students in 1st grade actally performed better on their STAR 360 assessments in 2020 than in 2019. That can be attributed to more parents being at home and having more time to help their young children with schoolwork. Higher grades have seen a slight dip in reading and math skills overall, though the dip was greater for Latinos.

Overall, Superintendent Donna Lewis said, the majority of Goleta Union kids are performing at or above grade level. What has helped make them an outlier in this way? She believes it is professional learning communities.

Professional learning communities (PLCs) are an ongoing process in which teachers work collaboratively across grade levels to plan lessons and to implement new strategies. Ned Schoenwetter, principal of Ellwood Elementary, explained the district’s PLC strategy. “Teacher teams identify those five to seven key learning standards,” he said. “Then they are talking to the grade-level teachers above them and below them so student learning is continuous…. We are teaching the key most important standards in depth rather than a lot of standards not in depth. The question is not if they will get it; it’s when will they get it.”

Craig Abshere, a 4th grade teacher at Ellwood who is in his 26th year of teaching, is convinced PLC methods work. “With remote teaching, we have a much smaller window of time to learn, so we really need to stay focused on what those skills are.”

Three years ago, Abshere was part of a group of teachers who put PLC structures they learned at conferences in place at Ellwood. He believes this gave the school an advantage during the pandemic.

Teachers at each grade level meet weekly to look at STAR 360 data. This helps identify different techniques to help those students who are not making progress. “PLCs have invigorated my last years as a teacher,” Abshere said. With PLC methods, teachers will be able to pick up the pieces of learning loss when classes start back in person. “When we say all children can learn and all children can get these standards, we mean it.”

Santa Barbara Unified School District

Like Goleta Union, Santa Barbara Unified is still teaching in a distance-only learning model, and its students are experiencing the same widening achievement gap seen throughout the county.

Roughly a third of elementary students in Santa Barbara Unified have earned a 1 or 2 (out of 4) score in reading, writing, and/or math on their most recent report cards — a 10 percent increase in the number of students earning these lower numbers than pre-pandemic.

In the elementary schools, 85 percent of the students who are getting three or more 1s on their first trimester report card are Latinos.

One school in Santa Barbara Unified, however, was instrumental tackling that discrepancy head-on. “I had teachers and staff ready to take the kids back on campus back when we were first in the purple tier,” said Gabriel Sandoval, principal of Cleveland Elementary. “We also had identified struggling students even before cohorts. We had the data that showed who were not logging on and weren’t progressing. We used that to identify which students to invite back for small cohorts.”

The students invited back included special education students, English-language learners, students with bad connectivity or no study space at home, and others with needs.

Cleveland is also the only elementary school in the district that has all kindergarteners back in classrooms because they were able to get the staff together before COVID cases spiked. “Kindergarten is the foundation for reading, so we knew those kids had to learn in person.”

A program designed for students on the autism spectrum is taught in small cohorts, and this approach, according to special education teacher Eben Robinson, has allowed students to learn in leaps and bounds.

A 3rd grade girl with receptive language delays in Robinson’s class lived in a crowded home and had great difficulty with distance learning. “She needed to be able to touch things and talk to learn — Zoom just wasn’t doing it. Since we’ve invited her to the cohorts, she’s on the same grade level she should be now.”

Other elementary schools in the district are gearing up for the longer-term solution to learning loss. Over at Franklin Elementary, Principal Casie Killgore devised a four-tiered system for determining what level of intervention a student needs to make up for learning loss — including summer school.

Students with less than 20 percent learning loss are placed in Tier One. They work in small groups in their classrooms, and their families are offered night programs to help them create home structures so that their children can perform better academically.

Tier Two students have 20 to 40 percent learning loss. They will go to summer school, have an extended school day, and enroll in small group intervention services. Students in Tiers Three and Four have increased programming support, including summer school and either night school or Saturday school.

Not all schools in the Santa Barbara district are working like Cleveland or Franklin is — each school is building its own plan to combat learning loss.

Teachers, regardless of their district, praise parents, who have had to step in and help teach their children when many were unprepared to do so. Patricia Garcia, with children in the 4th and 8th grades at Franklin, said, “It is hard to help them with the technology piece, and I am not as good with it as they are.”

Garcia spoke in Spanish, translated by 4th grade teacher Marlen Limon. “My husband and I both work full-time, so the kids stay home alone during the day. Luckily, my 4th-grader is doing better, and she is responsible with turning in her work.”

Limon said disengagement is the hardest battle for her students. She tries to get creative and asks herself every day: What excites a 9- or 10-year-old? “The social-emotional piece really matters,” Limon said, “so I check in with them daily and try to make that connection.”

The Community Steps In

In the greater Santa Barbara area, where there are struggling kids and families, there is a community working to back them. Throughout the pandemic, numerous nonprofits have tried to be there for any student who seemed to fall through the cracks — who, for whatever reason, stopped showing up to distance learning altogether.

The United Way of Santa Barbara County, for example, launched the Learning & Enrichment Center Collaborative, which serves 501 students across Santa Barbara County. The program provides a place for students to do their distance learning during the day with adult supervision.

It serves students who don’t have Wi-Fi access, someone at home to supervise them, or a learning area in their home because of overcrowding.

The United Way funds go to sites that partner with districts all over the county, such as the YMCA, Girls Inc. of Greater Santa Barbara, the Isla Vista Youth Projects, and the United Boys & Girls Clubs of Santa Barbara County.

“The staff walk up and down and make sure kids are on their Zoom and assisting them,” said Michael Baker, the CEO of the United Boys & Girls Club of Santa Barbara County, one of the sites that gets funding from United Way. “That happens from 8 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. They eat lunch at their desk. Academic instruction is done at 3 p.m.

“These kids really need the social interaction, too. Being in a room with 13 other kids is better than being alone at home.”

Jamie Collins, the executive director of Girls Inc. Carpinteria, described a typical day for a 1st grade girl. She arrives at 8 a.m. and then checks in with her Zoom class at 8:15, when Girls Inc. facilitators are there to help her. Following that is an enrichment program, and thanks to a grant, they have hired a physical education teacher for the afternoons.

“The unrealized stress of pandemic isolation on the kids is really being seen in their behaviors and how they relate peer to peer or to their Zoom calls,” Collins said. “The kids feel like they are just a little box on the screen, so our facilitators work to mentor and fill in that gap.”

Many local church groups have also pitched in to help mitigate learning loss.

Bob Niehaus, who attends Calvary Chapel, is leading the Santa Barbara Learning Center movement. He recognized that not only were most younger children not learning to read using the online format, but it was even worse for kids without Wi-Fi or parents who couldn’t be home.

Calvary Chapel, which can provide space for 20 students, was the first church to open its doors as a learning center. Though the learning center is not a religious program, Niehaus said if a child pointed to a picture of Jesus in the church and asked who he was, they would definitely “have a conversation.”

Shoreline Community Church is also offering a learning center but can only accommodate seven children. Overall, there are around 10 churches that are volunteering to be a learning center.

Though the effects of learning loss on young Santa Barbara students won’t be felt immediately, some will be able to get back to grade level sooner than others. And the social-emotional toll of being isolated from peers and teachers is difficult predict. But while the children are living through this pandemic, parents, teachers, and community members are all making every effort they have at their disposal to bridge the gap.

You must be logged in to post a comment.