The Segregationist Past Rises Again

Fair Education Santa Barbara Would Turn Back the Clock on Education

When Fair Education/Impact Education Santa Barbara lays out its program for local education, it sounds eminently reasonable. The organization wants local schools to emphasize math and language arts literacy and provide more vocational education programs in secondary schools.

But when these proposals are paired with Fair Education/Impact Education’s opposition to ethnic studies and anti-racism training for educators, their project takes on a more troubling form. If they win, they could significantly alter education for our children in ways that would increase inequality.

Scratch the surface, and their positions evoke the segregationist past of public education in the U.S. Basic literacy efforts and “vocational education” have long served to track students of color into lower quality education. Historically, “remedial” classes, along with wood shop or agriculture classes, worked to keep students of color in low-paying, manual occupations.

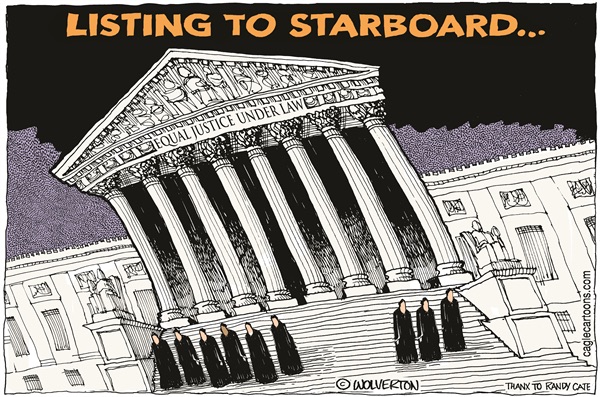

Most Americans know that Brown v. Board of Education declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. But it was never that simple. Before and after this 1954 Supreme Court decision, racism warped public education.

The first few years after the Civil War offered a glimpse of what could be for Black Americans. Thousands of public schools appeared in the South, thanks to the efforts of the Freedman’s Bureau, Black churches, and Protestant missionaries. Newly freed slaves flocked to these new public schools to learn to read and write.

Reconstruction represented a short-lived period of racial integration that extended from schools to politics. More than 2,000 African-American men held public office, and these Black legislators worked hard to secure funding for public education.

By the late 1870s, the promise of Reconstruction had faded. Throughout the U.S., white-controlled governments steadily introduced laws to segregate all facets of society. Underfunding public education was one element of this wider project.

Still, African Americans persevered. They continued to see education as a way to uplift the entire community. Black teachers and principals worked tirelessly to educate Black children. Some established private schools to provide a classical education of language, math, arts, and science.

This is when “vocational education” took on its segregationist meaning. Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown in North Carolina, for example, had to pretend her school focused on “manual training” to secure donations. This is because whites — even progressive whites in the North — would not support well-rounded education for Black children.

Although Brown v. Board of Education ostensibly ended segregation, white southern resistance to school integration weakened Black schools and communities. White school boards closed Black schools throughout the south. African-American teachers and principals lost their jobs.

Integrated schools, meanwhile, were dominated by white teachers and white administrators. African-American children attending integrated schools faced harassment from classmates and teachers. To avoid contact with Blacks, many wealthy white families enrolled their children in private schools.

This history reminds us what’s at stake. We can continue on the long, hard path to equity in education, where we implement evidence-based reforms — or we can go backward. When Fair Education candidates advocate for basic literacy and “vocational education,” I hear a retrograde call to return to white-dominated schools of the past.

Despite years of efforts to create more integrated schools, equity gaps remain. Current research tells us that it is possible to close these gaps.

Teachers and administrators can create school environments that support students’ social-emotional well-being. Curricula in which students can see themselves have been shown to improve student success.

Teachers and administrators are in the main white, so anti-racism training is also a significant way to help students of color. Recruiting and hiring more teachers of color, research shows, improves the academic performance of all students.

The Ethnic Studies requirement can also help close the equity gap. It allows students of color to learn their own history. Studies show that ethnic studies classes result in higher test scores, increased graduation rates, and greater career success.

White students also benefit. They receive a broader understanding of the society, equipping them to succeed in a more diverse world.

We can all agree that schools should be teaching students to read, write, and think critically. Ethnic Studies is just one more way to do that.

You may be wondering why I keep enclosing “vocational education” in quotation marks. The term “vocational education” harkens back to the kind of “manual training” in laundry and agricultural work that white donors insisted Dr. Brown provide her students.

These classes are more correctly termed Career Technical Education. We know that students who take STEM-oriented CTE classes are more successful in college. Santa Barbara Unified already provides these classes through its academies, such as Multimedia Arts and Design (MAD), Visual Arts and Design (VADA), and Engineering Academy.

Our focus now should be on ensuring that students of color are equally represented in these programs — not to revive non-STEM classes that offer limited career possibilities and fewer educational benefits. No one should advocate wood shop as “practical skills training.”

Kids deserve schools in which they can thrive. And we need to build those schools. Returning to old, failed, inequitable policies — like those advocated by Fair Education/Impact Education candidates — is not the way to do it.

Danielle J. Swiontek, Ph.D. is a professor of history at Santa Barbara City College. Her children attend schools in both the Goleta Union and Santa Barbara Unified school districts. The opinions in this article are her own and do not reflect the views of Santa Barbara City College.

You must be logged in to post a comment.