Interpreters Are Independent Contractors

The Profession Was Harmed by AB 5; AB 1850 Fails to Include Them

Lawmakers should save interpreters’ livelihoods, not pay lip service.

When disaster strikes, we look to state government to help with emergency shelter, health, and hunger relief. But what about a disaster actually caused by Sacramento?

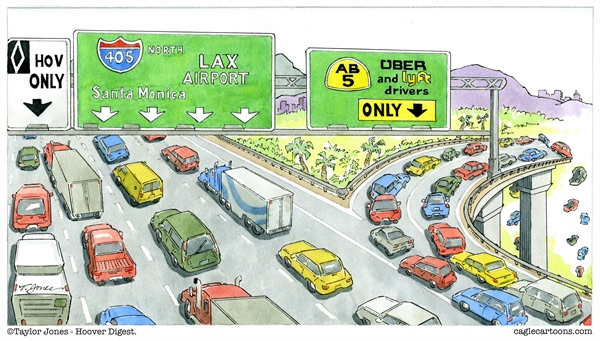

Such is the case with a state law, AB 5, that has harmed thousands of professional translators and interpreters, including us. It was intended to rescue misclassified workers from exploitation. But the law wrongly imposes employee status on us, even though we are freelance professionals whose control over rate-setting, availability, and client selection makes us independent by choice. Now even the terms of a new bill, AB 1850, intended to clean up the law, exclude all interpreters. We call on state senators to fix that.

You may not rely on the essential service we provide. But everyone must care whether state lawmakers, once alerted to it, actually clean up a mess they made. This month marks the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, signed in July 1990. Since COVID struck, interpreters proficient in American Sign Language have appeared each day at televised press briefings, exposure that has deepened public appreciation for our profession. But unless state senators include professional interpreters in AB 1850, access to expert signers for the deaf and hard of hearing in California will be sorely compromised. How sad if lawmakers let that become the headline at what should be a milestone for disability rights.

Professional interpreters are highly trained experts, not merely bilingual people. We demonstrate our proficiency in many ways, including degrees from accredited programs, credentials by agencies that set standards of excellence, and certification in a few languages for some settings offered by state government. The path to achieving professional status and keeping it, with continued training, is arduous. We don’t, to quote one state lawmaker, “just wake up one day” and hang out a shingle. Nearly two-thirds of professional interpreters are women, including many immigrants and people of color.

Local lawmakers have fallen short on efforts to protect the livelihoods of professional interpreters. On May 14, State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson sounded a sour note at a hearing of the Senate Labor Committee. She underplayed the overreach of the current labor law. “It’s kind of taking away the lollipop that they had: The ability to decide essentially when they worked.” This remark made light of the danger we face to our professional livelihoods, which are rooted in flexibility and independence validated by years of court precedent. She can undo the damage by including professional interpreters in AB 1850.

For her part, Assemblymember Monique Limón, who in this November’s election is poised to succeed Jackson, took to the Assembly floor on June 10 to applaud women entrepreneurs. “California is home to the greatest number of women-owned businesses in the nation,” Limón intoned. “Realizing the economic potential of women-owned businesses requires changing policies, business practice, and attitudes,” she added.

But the very next day, on June 11, Limón voted to approve AB 1850 despite the fact it omits interpreters, who are predominantly professional women. Constituents throughout the state raised concerns with her and Assembly colleagues about the exclusion. The author of the bill pledged that Senators would rectify the problem. We ask Assemblymember Limón and Senator Jackson to make sure that happens. Protecting the livelihoods of highly skilled interpreters is one good thing they can do to show they have the backs of women professionals.

Both Senator Jackson and Assemblymember Limón voted for AB 5 in 2019. Many lawmakers believed it merely set a state court ruling into law and redressed the abuse of independent contractors by ride-share and delivery titans who exploited the work status of their hirelings.

In fact it did much more. The law imposed an artificial definition of employee on us and the 75 percent of professional interpreters who work at our own direction among 30, 40, or even 100 distinct clients in a given year. Our livelihoods are built on independence, with credentials cultivated through years of expert service.

The health emergency and recession have turned the usual trials of our professional lives into all-out tribulation. Intruding into our capacity to work, just to insist that we be on someone else’s payroll or obtain a W2 tax form, is itself exploitative, irrational, and wrong. In current form, only “certified translators” are spared the requirement to be an employee in order to work in California. By substituting just four words — professional translators and interpreters — state senators can go from lip service to saving our livelihoods. It’s simply the right thing to do.

Connie Harmon is a National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters (NBCMI) certified medical interpreter who lives in Santa Maria. Antonio Verdiny is a state certified professional interpreter who lives in Ventura and, like Harmon, specializes in Spanish.